I'm Shirien Chappell, Head of Access Services at the University of Oregon Library.

I'm delighted to be here, and I very much appreciate your attending this session. That you would choose to spend the better part of an hour listening to me is both an honor and very humbling.

I was asked to talk about how supervisors can help staff go through changes. In preparation for this I sent a survey to several listservs, to staff both inside and outside of ILL-land, and to friends and family. I asked people to tell me about their experiences with change: what worked, what didn't, and what they learned. I got some really great replies: they were very thoughtful, insightful, and gave me a lot to think about. I thank those of you who took the time to write to me. I'll be sharing some of the responses you all gave to me a bit later. Given what I learned from the surveys and from doing some research and some soul-searching, I decided to modify the topic of my presentation. Here's the plan for the next hour: first, I'll talk about change in general, then about how supervisors can help staff through change, then I'll talk about ways that we can work within ourselves to navigate change most successfully. I will leave time at the end for your comments and discussion.

You know

the

Ben Franklin quote:

Given cloning and cryogenics and the special relationship some wealthy

corporations have with the IRS,

I think it should

be modified to:

The volume and type of changes we're experiencing in our lives and our work lives is relatively new.

I remember when I first began my life at the University of Oregon Library. Every day, every week was pretty much the same. I came into work, filed checkout cards, helped patrons at the desk, and processed overdue fines. There wasn't much variety. There was a lot of work, but not a lot of variety. It was that way for quite a few years. We did not have to learn new software to perform our daily tasks, nor adjust to the next enhancement or counter-enhancement of each upgrade. We weren't asked to figure out what procedures we could stop doing because our student budgets and work study allocations were shrinking dramatically. We weren't being asked to think Big Thoughts about how the library could provide different or better services more efficiently.

Another thing about those days: we had a captive audience on campus. Most students and faculty got most of their information needs met through the library. The library had the expertise to connect our students and faculty with the resources they needed; we had librarians who were expert searchers who performed mediated searches of databases since there was no patron interface to those databases; we thought we knew what was best for our patrons and we dished it out to them as best we could.

And then it all started changing. Students started finding what they needed on the web and faculty started keeping their own databases of articles and sharing them with colleagues across the world. People could get books fairly inexpensively and very quickly from Amazon. Students and faculty discovered that they could be self-sufficient; they didn't need us in the same way that they used to.

So, in order to remain viable we began looking at what we were all about. We started asking our patrons what they needed or wanted from us. We started listening to them and looking for services and products that we could provide that they couldn't get by themselves. Also during those times our economies continued to go downhill and as we lost funding we had to find things to stop doing.

We've begun a never-ending process of self-examination and change: we're providing different services and stopping or dramatically changing some of the services that we used provide. We no longer dictate what our patrons get: we respond to requests and needs from our students and faculty. And those needs frequently change and that's not going to change.

Another thing: we are experiencing an extraordinary rate in technological and cultural changes. Ray Kurzweil spoke about the speed of technological developments in an EDUCAUSE meeting in Denver. He says that we're right at the beginning of a time where really important discoveries and inventions will be coming more quickly than they ever came in all of history. The "X" in this picture shows where we are right now -- we're right on the verge of some really huge changes.

I'm not sure anybody's an expert on change -- I certainly am not -- but all of us live with it every day, sometimes every hour. If we have so much experience with it, I keep wondering why so many times it's so darned hard to deal with it.

I think it's because most of us, even those who call themselves "early adaptors" to change, need some sameness, some routine in at least part of our lives. There's security in things not changing on you; you know what the expectations are, you can learn the routine and be comfortable knowing what the grading scale is and how you measure up. Familiarity is comforting: it can bring strength and stability to one's soul. Why do you think all the McDonalds look the same around the globe? Why do we sing the same songs every year at holiday season? Why do little children love to have the same bedtime story repeated over and over and over and get grumpy when you skip a page or two? Because these routines are familiar and comfortable; they can be counted on.

Change means moving from the familiar to the unfamiliar. By definition, change means loss: a death of something we knew or were comfortable with. We lose our sense of belonging, our feeling that we know what our future holds. We can lose our sense of purpose if we don't understand what brought the change about. We can lose our sense of control when things change without warning or without reasons that we can understand.

When our routines change, or when philosophies and policies that we've been operating under change, or when our jobs change or our coworkers change, we experience a little death, and death, whether little or big, needs to be acknowledged and grieved. It shouldn't be ignored or diminished or put down; it needs to be respected and experienced. It's a mistake to downplay or ignore the effects of change on ourselves and our staff.

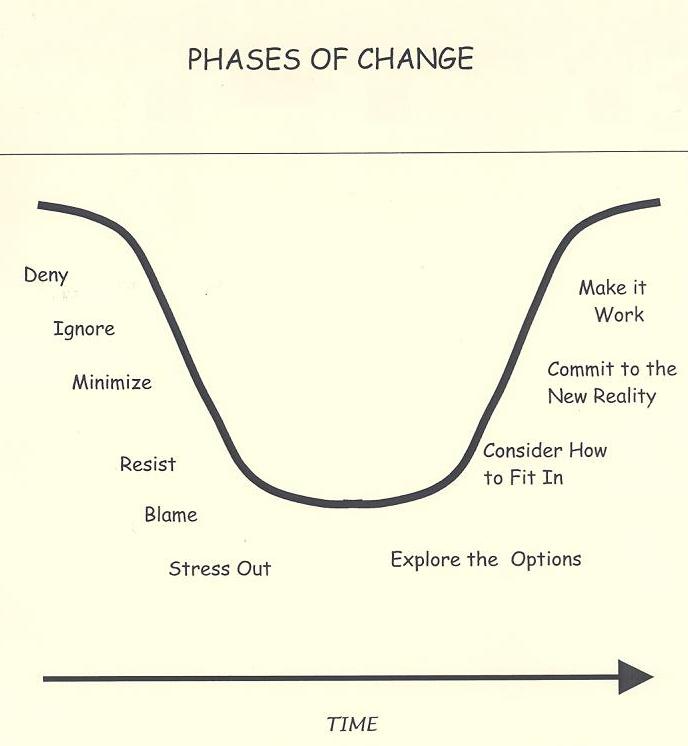

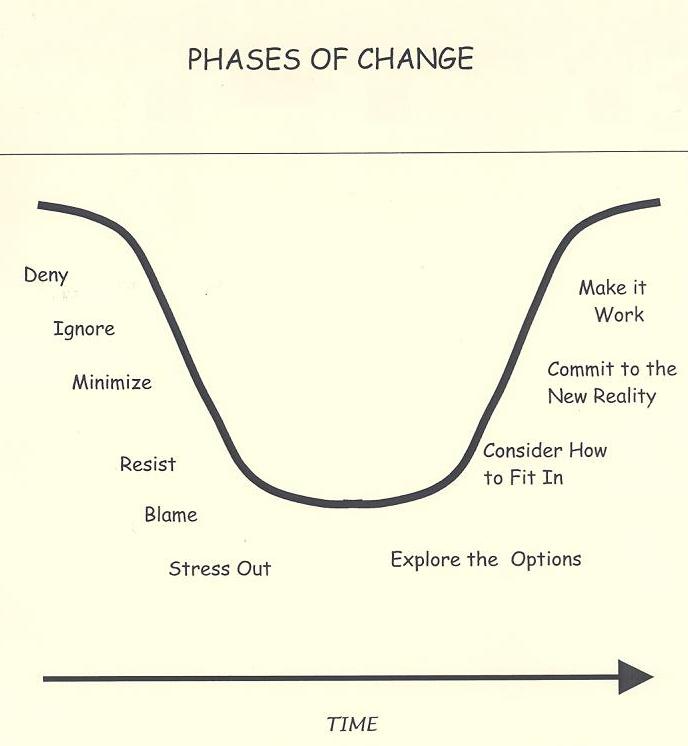

Kathy Hoge gave a workshop on "Navigating Change" to middle managers at the UO Library in 2006. She shared the following cycle of change:

It resembles Kübler-Ross's five stages of grieving, doesn't it?

There are good ways and bad ways to approach and plan for and

present and implement and respond to change. I believe this:

how

individuals respond to change is mostly within their own control. I

also believe that administrators and managers and co-workers can help

make the transition easier. Let's talk about how.

Hoge said that people in various levels of the organization have different pressures on them during times of change.

- Those folks who are at the center of planning for the

change, or the upper management who is requiring the change, may isolate

themselves in planning meetings. They frequently postpone communicating

to the organization about the changes because the changes are still in

flux. Sometimes they think that all the staff will just accept and

support the changes; they don't remember that many of the changes are

brand new to staff who haven't been in on the planning. When staff don't

support the change, these folks can feel betrayed that all their hard work

and all the integrity and good intentions to minimize the impact on staff

aren't appreciated.

- The supervisors who are expected to implement the changes often don't

have enough information about the change, yet are expected to deal with

employees who are in denial about the change, or who are resisting,

blaming, or stressing out. These supervisors are pressured to keep the

regular work running smoothly and support the change, and they can feel

betrayed that all their good intentions and hard work to minimize the

impact of the change on staff

aren't appreciated.

- Staff going through these changes have all kinds of pressures that I talked about earlier: loss of familiarity, security, anger, depression, surprise, frustration, resistance and they want and expect their managers to be supportive of them, or with luck, make the changes go away.

So, back to the phases of change diagram:

All people go through these phases when dealing with

change. Some people go through the phases faster, some slower. Some get

stuck for a while in different places on the curve. Some go through some

of the phases so fast you don't even see them go through it.

- When people are in the "deny, ignore, minimize" stage,

you might be hearing them say these things: "This won't happen.

It's

impossible. What we're doing

now is just fine. It'll blow over. We just need to make a few minor

adjustments to what we're doing now."

Supervisor responses to people in this phase should be to repeat and repeat that there WILL be change and explain why it is necessary. Supervisors should explain what will happen during the change and how it will affect each person. They also need to be patient while people work through their emotions.

-

For folks who are resisting, blaming, and stressing out, you'll hear:

"It's the fault of those jerks. This is horrible. You'll never get me to

do this. I feel sick."

Supervisors should let people vent, and not criticize them for how they feel. They should repeat why the change is needed, and be prepared for dips in productivity and quality of work.

- For the folks who are exploring their options and figuring out how

to fit

in,

supervisors might hear: "What are the possibilities? I'm not sure how

to do this.

Tell me again what the goal is. Maybe I'll survive this."

Supervisors should focus these people on new goals and new ways of doing things. They should accept that things will be chaotic for a while, and provide staff with time to learn and practice.

- For the staff who have worked their way through and are now ready to

commit to the new reality and support it, you may hear, "Here's how I'm

going to do this. I understand how this works. This might wind up OK for

me."

Supervisors should give people in this stage lots of positive recognition when they see new ways being tried, new attitudes being exhibited. Celebrate accomplishments of making the changes.

Generally, supervisors and co-workers need to be patient with themselves and others while everybody works through emotions and phases.

Communicating during changes should be face-to-face as much as possible. Make opportunities for staff to hear and talk with the people who mandated or instigated the changes. If the changes are coming from the top administration, the more staff hear these administrators share their philosophies and explanations about change, the more it is accepted throughout the organization. Everybody hearing the same things makes it easier to have peer discussions about them.

Also, supervisors can influence how people respond to change if, at the time they are hired, employees are told about the climate of change in the organization. If they don't do well with frequent change, they may choose not to accept the position, or at least they'll know what they're getting into from the start.

Even after the hiring process, if all staff hear frequently from the top administrators about change that is occurring throughout the organization, or even throughout library-land, it should come as no surprise (though it can still be a shock) when changes come to an employee's department.

At the UO Library we know that we don't have job security anymore; we have employment security. Our jobs are subject to change depending on the needs of the organization and we must be ready to learn different skills in order to help make the organization succeed.

Now let me share with you what you told me about what supervisors and co-workers can do or should have done to help transition through change.

- When I chose to move from one location to

another, I was met with extreme anger and judgment by some staff members.

I could have used some support after having made this difficult decision,

and would have preferred it if staff members had been able to not

personalize it. The way I was treated by staff at my old site has made me

not want to get close to coworkers at my new site.

- Being included in

all aspects of the process has helped immensely in past situations. It

would have been nice to be included more in the current changes we're

going through. Having change foisted on folks is difficult enough.

Making it nearly impossible is what happens when others working in the

current situation are not brought on board to discuss the changes, told

why changes are happening, asked for help brainstorming, etc. Just

because we are supervised does not mean we are stupid.

- Our reorganization came at the same time as the onset of menopause

(what timing -

stress plus hot flashes!) and other personal difficulties, I can only say

that

I was very grateful for my supervisor's support and good communication

during

the subsequent year. I think

my main point is that effective and timely communication is key, and

supervisor/colleague support is key. The worst thing in the world is to

not know what's going on or what's going to happen, and then to have to

wait for an inordinate amount of time for the shoe to drop.

- One supervisor told me this: people feel less able to cope with

change if it disrupts their

expectations, or if it is personally threatening. Unfortunately, most

organizational change does at least one if not both. Leadership can do

some simple things to help mitigate the impact:

- Set expectations at the time of hiring. People hired into the private sector have expectations that things will be changing constantly.

- Get in front of the personal angst. Anticipate who might feel threatened by a particular change and make sure those individuals understand early on what the impact may or may not be on them. Give them a safe place to express their concerns. Validate the concerns/emotions. (You may disagree with them, but they have the right to have them).

- Stay positive and supportive of the change. If management shows too much distress, it will have an impact on everyone else. Management has to be in synch as well. The worst thing that can happen is if some managers express doubt or lack of support for the proposed change. (This can make employees feel cut off and adrift).

- It helps not having

people giving unsolicited advice on what to do; it helps to have some

meditation time to think over what is happening and how best to deal with

it.

- Please, as a manager

remember that you might not know the kinds of unbearable strains people

are undergoing in their personal lives, especially as we all age. Thus

my

points about inclusion, listening, being willing to try their

suggestions, giving plenty of time (the Great Healer) before

implementing anything. ALWAYS BE HONEST and don't hide information or

prevaricate. If you can't say something because you've been told not to,

at least say "I've been told I can't discuss this."

- I don't think there is any way to make change easy for everyone. I truly believe that staying two steps ahead of the change, communicating with stakeholders, accepting and considering their input is how to make it manageable.

- In general, I'm big on being informed in a thorough & honest way. I want to have the whole framework given to me, warts and all, and then be told the goal we're working toward so I can think through the pros and cons and how they'll apply to the situation as a whole. I don't want a softened or sweetened presentation followed by a rah-rah speech about how we'll all pull through it together and it'll be fine.

- Change can create fear, in terms of fear of the unknown. So, information sharing is important, patience, time for questions (there are no stupid questions) and above all a sense that eventually everyone will be on the same page (optimism). A sense of humor can help. In the work place, I have watched change come to a halt for a variety of reasons. Change in terms of technology, in terms of changing job descriptions. Also, under-stimulation and low motivation because change cannot happen when it is needed. I think overall, we need employees that are committed to open sharing of information, centered emotional health and well being, instruction and workshops to teach the ins and outs of the change, a trial or slow roll out period so that all can get use to the change, and finally individual responsibility and commitment to the change being successful and meeting personal and organizational objectives.

- I think that in dealing with change you also have to remember

that you're dealing with ambiguity. In my experience, the more

ambiguity there is in a situation the harder it is to implement change.

If all of the cards are laid out on the table and people are aware that

change is imminent then it is potentially easier for people to accept

the

change. With that said, providing a space for people to express their

opinions, concerns, ideas, etc. could be helpful. But be up front with

them and let them know whether or not their contributions are going to

make a difference - is it collaborative decision making or is it going

to be a "town hall" environment where people can just be "listened

to". How you approach the change or deliver the message can make all

the

difference.

Also remember that collaborative decision making does not necessarily mean consensus decision making - so even though you might have heard everyone out about the changes, etc. it doesn't necessarily mean that everyone is going to be happy about the change.

If we could get people to think like my Dad when he says: "It doesn't have to be ok with me, to be ok" - then people might be able to swallow change a little bit easier.

- Another idea that helps me is the concept of relative flexibility based on skill levels and level of comfort with a person's current work. The staff who are not particularly confident in their current jobs are not going to feel equal to acquiring a new level of skill that builds on where they're afraid they should be but aren't. It's the same for people who think they're great but underappreciated and feel isolated. They aren't going out on a limb either. When we look at it in terms of skills, we can do something concrete to address it. Skills training. Skills build flexibility. The more you have, the more you can experiment, and the more you can learn. Learning new skills in the area where you are headed helps a lot.

- Helps a lot to give people TIME to work through feelings and ideas. Too fast is a killer. Some people process what they hear and others what they see, and many people can't take in an announcement in a meeting and the go right ahead and respond effectively. They need to go away and think about it because their immediate response is brittle panic and denial. Some people can't process written announcements and NEED conversations.

Whether change comes when you are surrounded by supportive supervisors who are doing all the right things, or whether it comes out of left field with no warning, how each of us responds to change is up to each of us.

Ok, I just can't resist. I have to say this: So, how many therapists does it really take to change a light bulb? We all know the answer: it only takes one but the light bulb has to want to change.

Some of the things I learned from the survey confirmed my belief that regardless of the surrounding situations, regardless of how skilled a supervisor one has, or how much information is made available, most of the power to navigate successfully through change is held inside each person. Here's what you all told me:

- For the most part, I think change is a good thing. It helps us to grow

and learn new things. It keeps our minds agile and adaptable. Something

that helps me deal with changes that I am not happy about is focusing on

the positive aspects of the new situation and trying to figure out what

aspects of the new situation are better than the old situation. Focusing

on the positive works wonders.

- Anyway, the thing that helped the most was reminding myself that I

needed to embrace change to stay youthful at heart and in my mind. I

adapted to the software changes quickly and most of the databases. I

still hate our new (3 years old) catalog because it never works

quite right--at least the staff version.

The learning piece here is that: 1) I can and will learn all the new stuff, even though I wish I was faster, 2) As a result of change, I learn new coping skills and actually have increased my roving reference skills! 3) Patience--mostly with myself.

Finally, my attitude is the only thing I can control. If I have a great attitude, others will enjoy my company and I may have fewer changes to deal with (keep my job). In fact others may help me learn new things--I have a great office mate who is 23 years younger and keeps me current!

-

It's much easier for me to deal with change if I can get a little bit

ahead of it. If I see something new coming but don't walk up to explore

it, I end up feeling helpless and without choices. That's a hard cycle

to break. For example when the government announced Medicare Part D

prescription drug coverage for seniors, I knew I had to make changes in

my mom's health coverage, but instead of finding out more about it, I

stubbornly hid my head in the sand. When I was finally forced to make

some choices or lose her coverage, I was angry about the process, at the

government, the insurers, and everyone else with their hands in her

pocketbook. I still don't like the program, but that's not the point.

It is what it is, and my feelings are largely self-induced. I would

have fared far better had I informed myself and come up with a plan from

the get-go. No one was stopping me. This experience makes it easier

for me to understand the "victim of change" syndrome.

- At work, I like change. When changes make sense, they feel like

progress, moving forward. I like to explain what changes I see coming

and why they are necessary as far in advance as possible, with regular

repetition to get people used to the idea and join the discussion. Many

of the people I work with feel excited like me; others tend to be more

moderate and bring up potential issues for consideration, which is a

great balance. On the other hand I can count on a few staff members to

resist passively, doing everything possible not to implement or be

affected by the new developments. At least one person will become very

angry about any proposed change and quickly devolve to the personal,

looking for hidden agendas, someone to blame...just like me and the

insurance industry.

- I guess the thing that works best for me is to:

Expect change, rather than resist it

Concentrate on what I like about the "new" (system, etc.)

Find humor--with the help of others

Imagine how it could always be worse--strangely, it helps to do this!

Re-concentrate on what I like about the "new" (system, etc.) again and again

Take time out (break/vacation day off to realize what is important to me & it will all be OK)

Enjoy the process of learning as much as possible, knowing I will not be an "instant expert".What really worked for me personally, was learning my learning style. I hated to feel "stupid" and when I finally realized that it was OK not to understand everything right away, and that I would figure it out with a little time, I was easier on myself and now I LOVE change. Or at least I love learning, and part of that for me, means being "dumb" for a while, but being rewarded with competence or my own sort of "expertise" in the end.

It also helped me to train others. That is a great way to learn--to be part of the process of the change when possible. It helps empower people who like a sense of control too.

- When change occurs that doesn't involve people, but circumstance, I find myself returning to teachings of my childhood and holding on to that which is good. I have to believe in my religion and that there are higher forces that know all things, including what I am going through at the moment. That is comforting.

- It helps to continue to do the familiar small things that are good---taking care of myself by eating well, exercising and sleeping sufficiently, giving service to others in small ways. Going to work is a good thing because it generates income, it provides a service to others and helps me not dwell on my problems.

- What works for me: don't get too stressed out about what's

happening

in your life. I've heard it said that if you have problems that can be

solved with money, you don't really have that big of problems...not sure

I completely agree, but having had my health threatened one time put

everything else in perspective.

- I think change is not difficult. How we face change will make the

change difficult or not. It is hard for us to do a different task every

day. We generally are happy when we know what is coming, due to the way

we were raised. I think, if we realize today is not going to be the

same as tomorrow and day after tomorrow will be very much different than

today. Our minds are more ready for the change and change will not be

difficult. Change is the way life is. This may sound like some

Chinese saying but I often realize I have made the day harder on myself

by trying to hold on to my way of things. Often letting go and flowing

with the change is not a bad thing.

- I think that working through the frustration of "why is it taking me so long to catch on to this" was just something that I knew HAD to be done, and the quicker I got at it, the sooner I'd learn it. It helped having gentle teachers. THEN, when I finally "got" something, I tried to (and I've always done this) emphasize to myself how GOOD it feels, how satisfying, really, and that always gave me encouragement to keep on. CHANGE is just something you have to adapt to. It helps to be able to look back over a (long?) life and say to yourself, "Well I made it through this or that, earlier,...I'm sure I can do it again."

Based on these insights and on some soul searching that I have done, and on readings, I offer these ideas for how to approach change on a personal level. Some may be harder for you do to than others; it depends on where you are in your change cycle.

- Accept that change is inevitable and that it's happening to you

right now.

- Take some time to examine your feelings about that change.

Whether you're angry or

pleased, just look at those feelings and accept them; realize that

they're normal.

- Decide where your limits are: decide at what point you will no

longer participate in the change. What has to happen before you quit

your job, divorce your spouse, move away, discontinue treatment, end a

friendship, disinherit your kid, change your religion.

- This next step gives you some breathing room so that you can

examine the change without panic. Look

at the change and imagine the worst case scenario. Does that

worst case cross over the boundaries you just set?

- Now find good side to the change: Can you learn new skills and be

more marketable in the future if you weather this change? Also, are

there any good things that can come from this change? Sometimes

you must lose something in order to make room for a new and better

thing.

If the

divorce goes through, maybe someday you'll find your

real soul mate. If you have to report to a new boss, maybe that boss

will fall in love with your ex and they'll move away and you'll be

promoted. Maybe the loss is worth the future gain.

- Now you can choose how you're going to respond.

Jack Canfield wrote a book called Success Principles.

- Remind yourself about your past successes. You've gone through

changes in the past, and some of them went well. Examine what you did

right in those situations. What did you learn through them, what

attitudes were you able to change to allow you to succeed?

- Make a list of the things that are still the same. Reminding

yourself that not EVERY thing has changed will provide some comfort.

- Talk with others: co-workers, counselors, trusted friends and

relatives. Choose people who will give you viewpoints that are

different from yours. Also, talking with others may give you stories of

their challenges that might make your own seem smaller. You might find

that if others made it through their personal changes, you can, too.

Caution:

We sometimes set people up to agree with us, e.g. "You won't believe

what those idiots have done now!" When seeking advice or support from

others, try to remain as neutral in your delivery as possible. That

way

you will set yourself up for a more honest (and useful) response.

- Put your fears on hold and openly experience the change. See what

it really feels like without being magnified by the fears and concerns

you had. Try experiencing the change with a confident attitude and see

if that makes it feel better.

- Be creative. Try to get your "best-case scenario" to come

true: get something beneficial from the change.

"Never waste a good crisis." Find something to learn, something to

improve, something to let go of in this transition.

- Be watchful and be open. If the situation gets

close

to the boundaries you identified earlier, then reexamine your

boundaries. Maybe they've moved farther out. Maybe you've discovered

some good

things about this change, now that you've experienced it, and those

boundaries have changed or have moved backwards. If they haven't, then

start thinking about what you need to do get out of the situation.

- If you find that they're unfounded, let go of your past fears about

this change. No need to carry the baggage around; you need the room

for your new skills and attitudes.

- Share your successes with others who are having problems with the

change.

- Remember what you are learning through this change so it will help you during the next change.

We humans need balance. When one part of our lives is in upheaval be sure another part is solid. If you're having problems with your job, then take actions to keep your home life, your real life, solid. If both of them are out of whack, then concentrate on keeping yourself healthy and fit. Or reaffirm your religion or faith or philosophy of life. Or volunteer to help other people -- do something to keep some part of your life in balance while you work on the part that isn't.

In closing, I would like to leave with you a little story:

A Zen master, while visiting the United States, wants to check in with a former student. The student is working as a New York City street hot dog vendor. The Master locates him and spends a little time visiting with him. As a way to show support, the Master wants to buy lunch from his student. "Grasshopper," he says, "Make me one with everything." The student gratefully pulls out a hotdog bun, slaps in the hotdog, slathers sour kraut on it, adds mustard, pickles, tomatoes, onions, ketchup, and relish and hands it to his Master. The Zen master pays the student with a $20 bill, and the student puts the bill in the cash box and closes the lid. "Grasshopper," says the Master, "What of my change?". The Grasshopper responds, "But Master, change comes from within."

Thank you so much for your time and patience. I've enjoyed working on this project -- learning about change is never done. I can use all the advice and help I can get as a supervisor and as a person, so if you have insights that we haven't talked about today, I'd still love to hear them. You can email me directly or use the webform here:

http://www.uoregon.edu/~shared/change.html

I think there's time for a few comments, so I open the floor to you.

N Smith: "When you live in reaction, you give your power away. Then you get to experience what you gave your power to."

Brian Tracy: "You cannot control what happens to you, but you can control your attitude toward what happens to you, and in that, you will be mastering change rather than allowing it to master you."

Carl Sandburg: "Time is the coin of your life. It is the only coin you have, and only you can determine how it will be spent. Be careful lest you let other people spend it for you."

Al Rogers: "In times of profound change, the learners inherit the earth, while the learned find themselves beautifully equipped to deal with a world that no longer exists."