The Doctrine of Double Predestination:

A Summary

The Doctrine of Double Predestination:

A Summary

It has become a commonplace of Reformation historiography to

decenter

the doctrine of predestination in the theology of John Calvin. Not

predestination

but justification was the fulcrum of his theology, combined with a

strong

sense of wonder and awe at the sovereign power of God; as William J.

Bouwsma

emphasizes, Calvin admired Luther highly and saw himself as fulfilling

what the latter had begun. By the same token, predestination was the

logical

consequence of any doctrine based on salvation by grace alone

--

which included the doctrines of both Luther and Zwingli. Finally,

Calvin

was not, strictly speaking, a “Calvinist,” in the sense that

predestination

came to occupy an ever more central theological role only after the

Genevan

reformer's death, when theological debate among Protestants became more

polarized and doctrinaire. As Alister McGrath puts it, Calvin's

religious

ideas may have been systematically arranged; those of his

successors

were “systematically derived on the basis of a leading

speculative

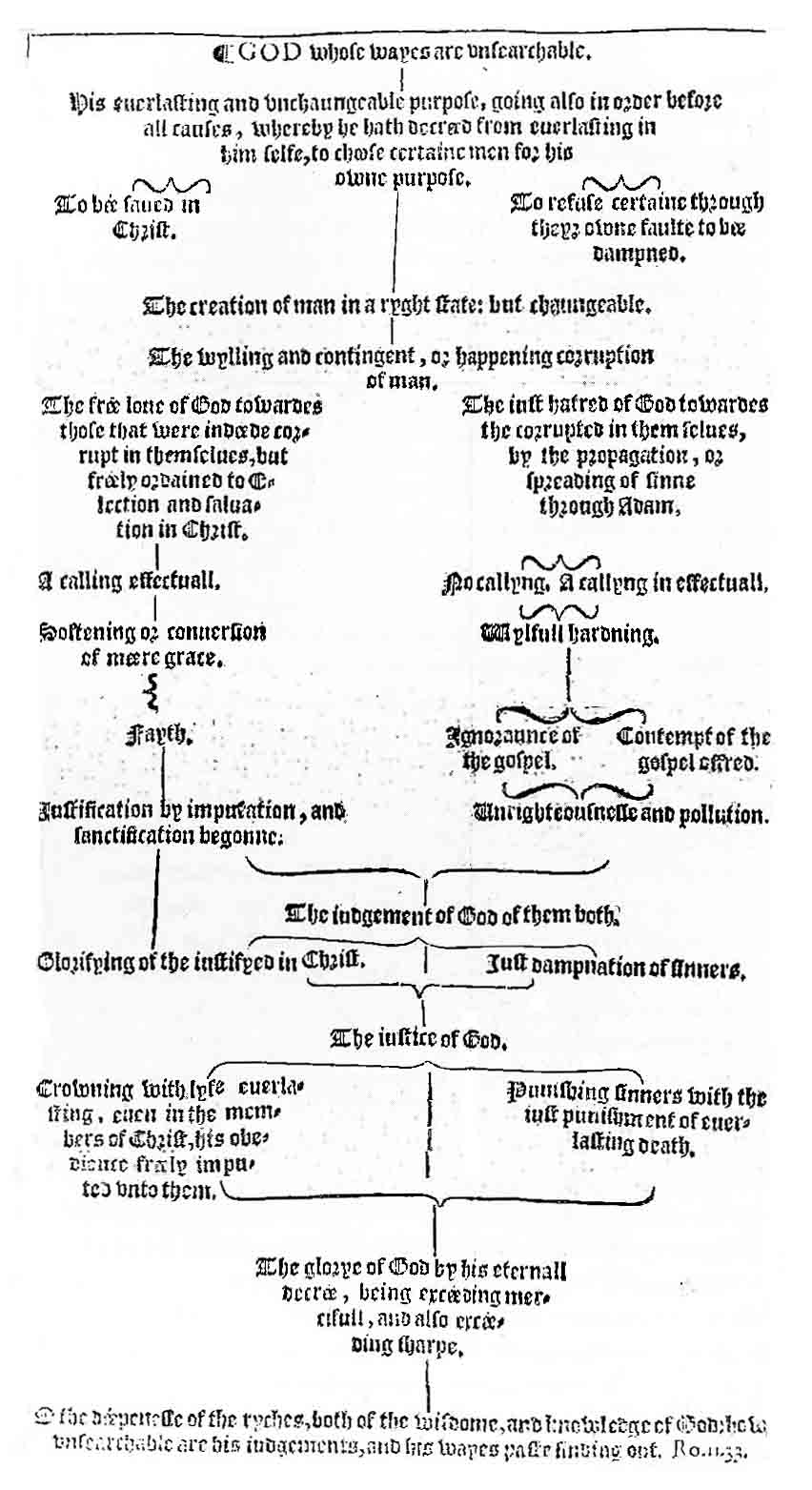

principle,” that of predestination. And yet this is precisely the

issue:

as with Luther on secular power, the historical importance of Calvin's

theology transcends the emphasis he placed on this element or that. In

this sense, the strong “popular” association between Calvin's thought

and

predestination is not misguided at all.

Image: Titlepage of Calvin's Institutes of Christian Religion (1556).