I admit there are some days when I find my job to be rather monotonous. Crank out some retrocon, withdraw some titles, fix some call numbers....It's all very worthwhile and good, but often it's not...well...imaginative, creative, exciting....

But sometimes I run into something that unexpectedly captures my imagination and makes the past seem immediate and touching. That happened to me recently when I received an older book to reinstate. The title had been withdrawn since 1985 and needed retrospective conversion. But when I looked at it with an eye to cataloging it, I realized the "cover title" was quite different than the title page... in fact, it wasn't a cover title at all.

Since I began life as a cataloger in the Library in 1987, I have had the privilege of dealing with a number of rare or old books, and it's possibly my favourite part of the job. It always gives me a thrill to dip into a cookbook from 1720, or pamphlets written when Charles II of England was still alive. That to me is part of the romance of cataloging! But somehow this particular book was especially interesting to me. Maybe it was the personalization of the binding, which I haven't seen much at my desk (although perhaps the official rare books catalogers have seen it more often). In any case, I became quite obsessed with it, and spent some of my own time tracking down the history surrounding it.

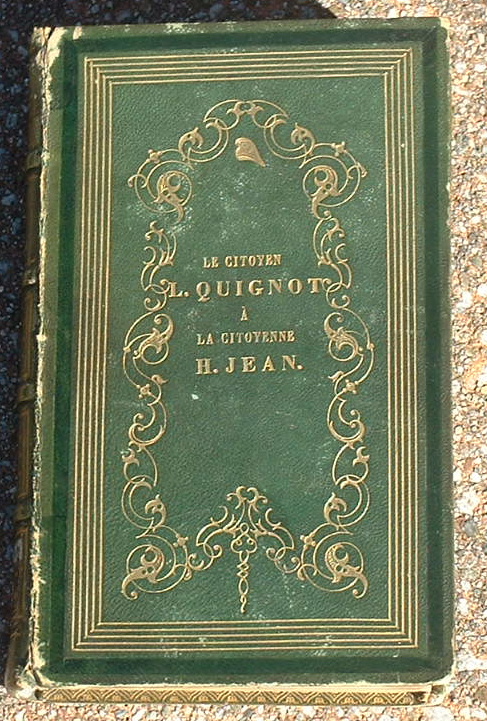

The book at my desk was Voyage en Icarie

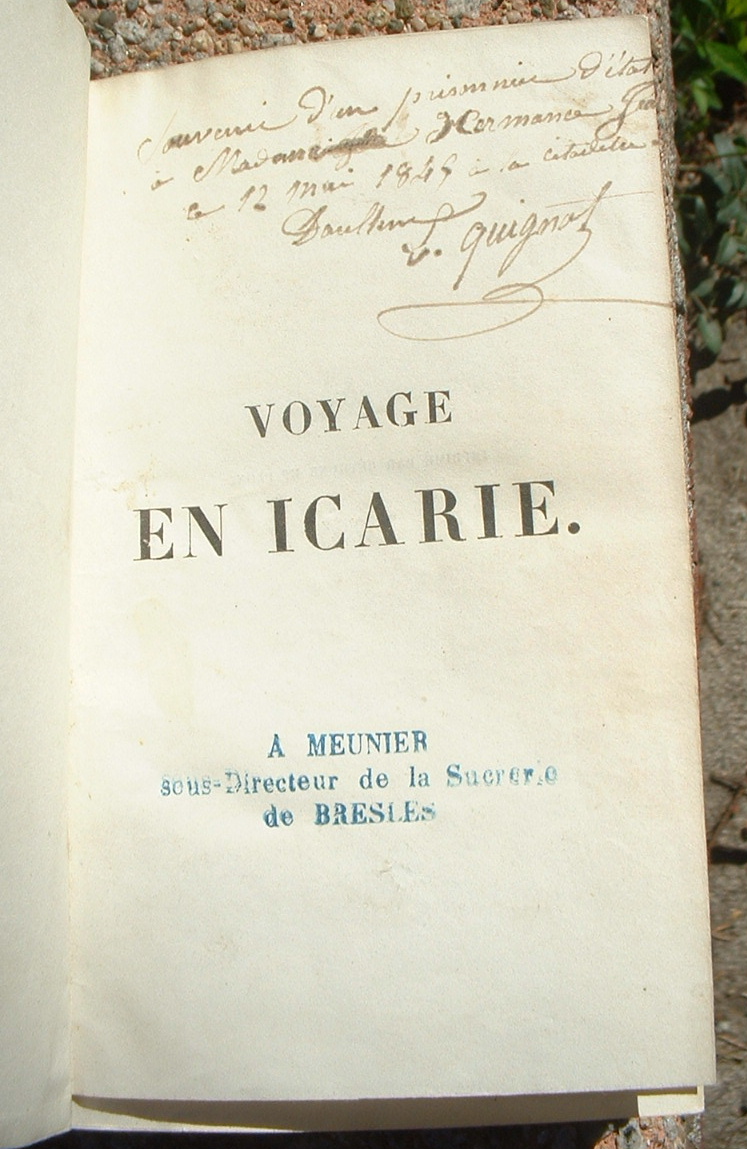

Photographs © LR Sexton. Click on images to enlarge.

and it's a Utopia of a sort by Etienne Cabet. On its beautiful smooth forest-green leather binding is some gold tooling, and in the center in gold the inscription "Le citoyen L. Quignot à la citoyenne H. Jean". Inside on the half-title page in fading brown ink is the inscription "Souvenir from a prisoner of state to Mademoiselle Hermance Jean, 12 May 1849....."

In Paris in 1837, Auguste Blanqui, a man who in a sense was a "professional revolutionary", and who was given the nickname "L'Enfermé" because he spent so much time in prison, had formed a underground group called the Société des Saisons. The group's aim was to overthrow the current government, and you can read their appeal to the citizens here. The part that interested me was this: "Le gouvernement provisoire a choisi des chefs militaires pour diriger le combat ; ces chefs sortent de vos rangs, suivez-les ! ils vous mènent à la victoire. Sont nommés : Auguste Blanqui, commandant en chef, Barbès, Martin-Bernard, Quignot, Meillard, Nétré, commandants des divisions de l'armée républicaine." In other words, "The provisional government has chosen the military leaders to direct the fight. These leaders come from your ranks, follow them! they will lead you to victory. Here named:".....The name that interested me was Quignot, commander of a division of the republican army. I was positive it was the same person.

I found a little information about Louis Quignot in Barricades: The War of the Streets in Revolutionary Paris, 1830-1848, by Jill Harsin. I also found a bit about him in Un républicain méconnu: Martin Bernard, 1808-1883 by Claude Latta. Louis-Pierre Quignot, a tailor and revolutionary of Paris, was the son of François Quignot and Joséphine Céjournant. He lived on rue Saint-Denis, was married with a child, and was about 30 when he wrote at least one position paper for the extremely secretive Société des Saisons in 1839. As a "commander of a division" he took part in the fighting of the "revolution" of May 12, for which he was sentenced to 15 years in prison. The Encyclopedia Britannica online says "Five hundred armed revolutionaries took the Hôtel de Ville ("City Hall") of Paris, but, isolated from the rest of the population, they were easily defeated after two days of fighting".

The second day, however, was an anticlimax; most of the enthusiasm and the revolutionary ranks having evaporated as the first day waned. Harsin's description of the whole event made me think how like a village or group of villages in many ways the Paris of the early 1800s must still have been. The revolutionaries had gathered in Right Bank cafés and bars on the morning of Sunday, May 12, 1839, and when the word was finally given, dashed off to construct barricades and overthrow the state — some paying the startled proprietors for their drinks and others not. The fighting was in places bloody, and was mostly done with hunting rifles and pistols. Estimates of insurgents ranged from 300 t0 600 men (including a handful of women as well) — far fewer than the revolutionaries had hoped for. And the masses did not rise on this occasion. By the next day most of the cobblestones had been replaced.

Louis and a number of his friends and fellow revolutionaries were in prison at Mont-Saint-Michel from 1840 to 1844, where their sufferings at length caused a public outcry. In October 1844 they were sent to Doullens, where they were given a bit more freedom, and engaged in gardening. Latta quotes Martin Bernard as saying that Louis's taste for gardening was such that he redesigned their garden plot each year.

The revolutionaries were freed at last when the success of the February Revolution in 1848 resulted in a change of government. They somberly left Doullens on 26 February 1848. Louis returned to Paris and his profession as a tailor, and was no longer visibly active politically, although he remained a close friend to Bernard (who at various times found himself in a position of influence, and in exile). He was Bernard's executor and one of the chief mourners at his funeral. Louis himself died in 1887 and is buried next to Martin Bernard in the cemetary of Monmartre-Nord.

But what of Hermance? She remains so far a mystery to me. Who was she? The most likely guess is that she was his wife, or daughter, if his child was a girl. It may be that her history is lost, or that I have simply not been able to look in the right place for her traces.

In any case she was important enough to this proud tailor and revolutionary from the barricades of Paris that he gave her a radical text bound beautifully and engraved with her name in gold for the world to ponder a century and a half later. One wonders — did they dream of travelling to join Cabet in the New World? The half-title page also bears the ink-stamp of A. Meunier, under-director of the "sugar-house" of Bresles (Oise, Picardie, in France). Impossible now to tell how the little book came from Bresles to the University of Oregon, although the older UO bookplate shows that it was purchased with the "English fee" money.

The UO Libraries hold many books that are signed by a famous author or have emerged from the personal collection of someone of significance. But for the most part their stories are known, the histories of their authors and collectors the subject of dissertations or articles in the popular press. This book fascinates me even more now because I know it was given by an obscure man from the working class who fought at least once on the barricades of Paris and survived his harshest prison sentence while retaining his humanity, to a woman he knew would appreciate the radical text. And he didn't just write an inscription, he bound his dedication with leather and gilt and both their names, and on it he stated his abiding position: he remained always not a "sujet", not a "tailleur", but a "citoyen".

What a world of romance passes through my hands at this desk!

This article appeared in the May 2004 LSA News and was republished in the June 2004 Library Mosaics, a magazine for library support statff (which ceased publication after its November/December 2005 issue.)

© 2004 Harriett Smith