Ming2

Summing up WINTER

With the founding of

the Ming the period of destruction related to the rebellions that ended the

Mongol Yuan dynasty gave way to a time of consolidation of the state visible in

the reconstruction of agriculture and administration.

The end of the Yuan

saw a rapid inflation, corruption of the Tibetan clergy who controlled the

Chinese clergy and interfered in political affairs, and rebellions of the

exploited Chinese population against Mongol and other foreign officials.

One of the rebellions

attracted the poor monk Zhu Yuanzhang (1328-1398)

who later became the head of a rebel army and successfully fought against

the Mongols as well as other contenders for power.

The Hongwu emperor, Zhu Yuanzhang

The Hongwu emperor, Zhu Yuanzhang

The Ming dynasty may

be divided into four larger periods:

1. 1368- 1450: The age

of economic reconstruction and installation of new institutions. Diplomatic

and military expansion were pursued in

The Yongle emperor, Zhu Di

The Yongle emperor, Zhu Di

2. 1450-1520: A period

of withdrawal and defence after the great expeditions. This period in the

eyes of orthodox Confucians was a time in which commerce disrupted the cycle

of agriculture and began to corrupt society. The polarization of the wealthy

and the poor began.

3. 1520-ca.1580: A 2nd

Chinese ‘renaissance’ among Chinese intellectuals during the rules of emperors Zhengtong and Zhengde could not

avert the growing imbalance of agriculture and commerce. Agriculture, so the orthodox

Confucians, was neglected, commerce dominated the

economy. The purity of working the land gave way to the excesses related to the

influence of capital.

Consumption, not

necessity, began to drive production.

4. 1580-1644: a

period of crises in commerce, politics, and revolts among urban workers

Phase I:

Society in the initial century of the Ming was characterized by a search for

stability through reconstruction of the agrarian social system (which had

been abandoned as early as the Song when a commercial revolution had propelled

the economy) and at the same time created physical and social immobility while

the population more than doubled.

► Agriculture:

restoration and reclamation of land

reforestation

transfer of immigrants to new territories, land

distribution

► Physical

immobility:

Travel was

discouraged. The maximum radius of travel in which no route certificate was

required was a distance of 58 km.

Transgression of this

law was punished (at times by capital punishment) at the time of return.

► Social

immobility:

Occupations were

hereditary. (This regulation actually had first been introduced by the Mongols

and belongs to those regulations that the first Ming emperor, Hongwu, did not discard instantly.)

The society consisted

of

• peasants

who had to settle in villages,

• artisans

who worked in state-service workshops,

• merchants

who were only allowed to perform trade in necessities,

• and

soldiers who were settled at the frontiers in large numbers.

• A small educated

elite whose members were generally more distrusted than trusted by emperor

Hongwu, managed the administration of the empire.

► A rural idyll was propagated:

Families had a house

to live in, land to cultivate in the predictable rhythm of the annual cycle of agriculature, hills with trees for firewood, gardens to

grow vegetables. Taxes were appropriate. Life was secure due to the absence of

bandits and military attacks. Moral values were kept high through a functioning

marriage and family system.

► Registration

for purposes of tax collection:

Households were registered

in official charts. In order to recruit household members for duty in the

labor service system, units of 10 households were combined to one ‘tithing’

(jia),

headed by a ‘tithing head’ whose position rotated annually;

units of ten tithings

were combined to a ‘hundred’ (li), headed by a ‘hundred captain’; his position rotated on

a decade basis.

‘Tithings’,

‘hundreds’, and their heads were supervised by six tax captains selected by the

local administration.

Mobility would

have distorted and in fact later did distort the systematic registration of

the population for tax purposes. In the beginning of the Ming, physical mobility

was only supported and at times required for

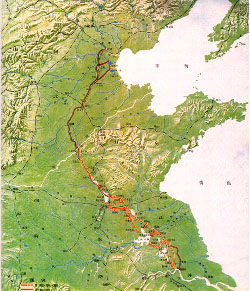

► creating

new settlements in the border regions in order to control military activities

of the neighboring peoples or states and

► creating a

new social fabric in the cities especially in the metropolitan areas when

households of former opponents of contenders for power were sent into exile as

settlers of territories that were to be newly cultivated. The population was

functionally divided and distributed.

► Uniformity in

official matters

Due to the loss/

transformation of state ritual and etiquette during the Yuan Dynasty uniformity

was required in costume and in handling official matters.

Models for writing

memorials were published. These models enabled not only educated officials but

also less educated commoners to formulate their ideas and concerns in an

officially accepted standardized fashion.

Memorials could be

handed in by commoners who -at least in one case transmitted to us- could

impeach a magistrate.

Each memorial that

was sent in had to be duplicated. The original was sent directly to the emperor

who wrote a statement and sent memorial and statement to the Office of

Supervising Secretaries. The office was created in the Ming and solely in

charge of handling memorials. It received the duplicate and matched it with the

original and the emperor’s statement. Every memorial was recorded in the

official Court Record. A handwritten summary was published in the Beijing

Gazette which also informed its readers about promotions, demotions, military

and diplomatic affairs, as well as news from the provinces such as natural

disasters etc.

When the Veritable

Records (Shilu)

were composed at the end of a rulers’ reign, the Gazette was one

of the sources on which the Shilu

were based.

► Officially approved physical mobility

was supervised by the Ministry of War which

managed

the courier service,

the postal service, and

the transport service.

Courier stations were

established every 35 to 45 km. They kept up to 450 horses and mules, and 50-60

sedan chairs (which had been introduced as a means of transportation during the

Yuan Dynasty) and the necessary amount of carriers.

The

47.004 full-time

laborers were in charge of maintaining the

Means of

transportation

horse, mule

sedanchair

wheelbarrow (max. load: 120 kg)

4 wheel mule-cart

(max. load: 3000 kg /375 km)

grain barge (average max. load 30.000 kg) made

of pine (exchange: every 5 years) or made of the more durable fir wood

(exchange: every 10 years)

Brook argues that

the tension created by the search for social stability caused the trend of

economic growth. Regional and national commercial networks were formed. Agriculture

developed from producing the means for subsistence to a production of surplus

which could be traded. The production of commodities used the improvements

in infrastructure provided by the newly consolidated state for its tax goods.

Mobility necessarily increased.

On an international

level the states roaming the ‘