Summing up Naquin/Rawski, chapters 1&2

Political

Structures

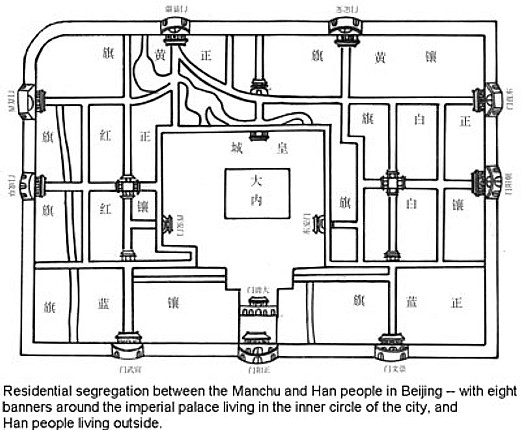

The Manchu, Mongol, and parts of the Chinese population were integrated into civil-military units called banners which again were divided into smaller units of approximately 7500 households each. The eight basic banners were identified by a colored flag (yellow, white, blue, red) with a plain or bordered edge. After more groups of the population had been integrated, there were 24 banners. By 1648 only 16% of the bannermen were of ethnic Manchu origin.

Banners were units in charge of registration, conscription, taxation, and mobilization. The army was led by Manchu aristocrats who were assisted by Chinese generals. The Mongols were fully politically integrated into the Manchu state when the seal of the Great Khan came into the possession of the Manchu rulers in 1635 after a victory of the Manchu over the Mongol army. Possessing the Great Seal aligned the Manchu ruler with Chinggis Khan, who had first united the Mongols in a strategy similar to Nurhaci’s unification of the Manchus.

The banner command initially was in the hands of the Manchu emperor, his sons and nephews who shared the rule. During a process of increased bureaucratization the privileges of the hereditary aristocracy were checked by the growing political power of the imperial clan members.

When the

rebellion of the Three Feudatories during the decline period of the Ming was

quelled, the Manchus successfully began to win the

sympathies of the culturally dominating elite of the

The Southern Inspection Tour of the Kangxi Emperor (detail)

New Institutions:

The Imperial Household Department was an institution newly created in 1661 that replaced the eunuchs in the management of the imperial household. (Eunuchs continued to work as servants in the harem only.) Now Chinese bondservants and officials

► managed the budget of the imperial clan

► provided for the emperor’s food, clothing, housing

► managed the imperial printing bureau

► managed the estates in

the bannermen

► supervised the monopolies of the sale of ginseng, salt, and pearls, the coin-copper

trade with

► the customs offices

The main institutions of the Qing

government:

Emperor personally advised by bondservants

▼

Central administration:

Six Ministries Censorate

new: Grand Council

Personnel 6-10 high ranking officials

Revenue (50% Manchu, 50% Chinese)

Rites personal consultants of the War emperor, drafted imperial edicts

Law

Public Works

new: Court of Colonial Affairs (in charge of Inner Asian matters; staffed by Manchus and Mongols exclusively)

▼

Local administration

18 Provinces (consisted of 7-13 prefectures): ruled by governor-generals (first ruled by Han-Chinese, after 1667: 50% Manchu, 25% bannermen, 25% Han Chinese)

new: bureaus for interprovincial grain traffic and maintenance of waterways

Ming army of the Green Standard was retained as a police force and absorbed local militias (which had not been abolished)

▼

Prefectures (consisted of 7-8 counties)

▼

1281 counties + 221 departments (in the end of the 18th century) managed by a magistrate who ruled over approx. 200.000 people

Officials’ ranks and examination system

Officials were graded in 9 ranks with an additional division in a (higher ranking) and b (lower ranking) attributes.

To obtain an official position exams on the

prefectural

provincial and

national levels had to be passed.

Winners of the national degree could also participate in the highest examination, the palace exam.

Two special examinations (1679, 1736) were held in addition to the standard exams in order to recruit important scholars for government service, but there were also additional exams on the lower levels from time to time which considerably increased the number of examinees (as well as the competition between them). Employment was given to many scho lars who passed the exams and did not obtain regular office by including them in the publication projects for imperial editions of the History of the Ming Dynasty, the edition of the Complete Library of the Four Treasuries (the result of the imperial book inquisition) etc.

Participants for the exams were selected according to a quota to insure that regions were represented in a balanced ratio. Bannermen competed in separate exams which allowed for special privileges.

Suppression of Ming loyalists

Ming loyalists

in the Southeast (especially in and around

The Manchu government faced the danger as well as the usefulness of the well-educated local elites. They could serve the local communities well, but at the same time they could also take over government functions which were part of the officials’ duties. In order to limit their influence, tax-exemption practices were changed: tax and corvée exemptions were no longer granted to the household but now only to the individual.

Minority communities were headed by chieftains of local tribes but just like in the Ming. Chinese colonists had to settle in many of these regions in order to sinicize the local population by providing schools and temples, and active promotion of Lamaist monasteries.

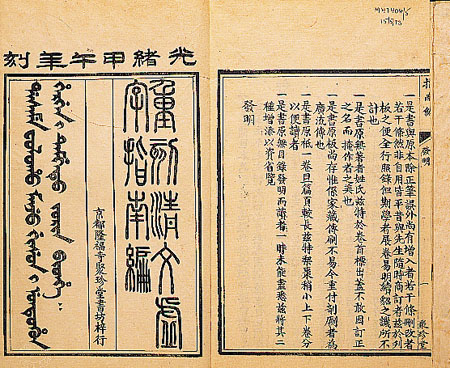

A ban of intermarriage between Han and Manchu proved to be impossible to enforce. Nevertheless, Qianlong insisted on the use of the Manchu language and learning of the Manchu script by the Manchu population. To preserve Manchu history and tradition he ordered the Manchu history to be written. In addition the history of the eight banners was composed, as well as the publication of Manchu genealogies and the recording of the shamanistic tradition of the Manchu people.

At the same time public morality was stressed following the pattern of the Ming Dynasty.

Six Maxims and Sixteen Injunctions where published by the emperors. They had to be publicly recited twice a month and demanded filial piety, respect towards elders, education of the children by the parents, and proper behavior from the common population. The demand for moral behavior was further strengthened by the many manual on morality that were published during the 17th and 18th centuries.

Economic rehabilitation

Economically the Qing managed to consolidate the state by tax exemptions for areas that had suffered damage in the takeover fights. In 1713, corvée tax quotas were frozen permanently and corvée and land taxes were transformed into payments of silver.

Land cultivation was intensified by planting maize and potatoes on a large scale. Peanuts became increasingly important and tobacco competed with rice and sugarcane for good planting land, because tobacco became a profitable crop. Several crops such as rice, wheat and barley could be harvested twice a year.

Due to the peaceful period and the positive results in food supply the population tripled between 1650 and 1850. In times of bad harvests, famine relief was paid to the victims who could then buy grain from reserve stocks in the so-called ‘ever-normal granaries’.

At times the government actively took measures to regulate and stabilize the economy. Between 1759 and 1762 the export of raw silk was forbidden because to many weavers had lost their jobs and foreign sales had increased local prices. Later the type and amount of silk that was bound for export was limited for the entire country.

Foreign

Relations

The tributary

system functioned as it had under the Ming:

envoys from

The

relations with

Different

from future encounters with other Western nations, contacts with

Social

Relations

Kinship

The basic

unit of production and consumption was, as it always had been, the family

clan using a common budget and common property. The clan was presided over

by a patriarch who made the essential decisions about family matters (marriage

alliances between surnames, usually diversified careers of sons, punishments

etc.). ‘Membership’ in a clan was indicated by the common family name; family

organization strived for joint efforts to keep up shared rites of passage,

gravesites, elaborately constructed ancestral halls in which the ancestral

tablets were displayed, education for the children, and recording the clan

genealogy. These shared institutions and activities especially in south and

central

Residence

and Community

Earth-god temples and temples of specific local deities served as neighborhood centers for countryside and city communities.

The spiritual hierarchy mirrored the secular hierarchy: the god of the stove was the deity of the family, supervised by the earth-god, who again was controlled by the city-god, just like the magistrate was the administrative authority for all lower-ranking officials and clerks.

Since the Song welfare activities that formerly had been associated with religious groups (predominantly Buddhist) had been taken over by well-to-do households (orphanages, public cemeteries, hospitals, schools, granaries, fire-fighting brigades and police forces etc.) This philanthropy continued throughout imperial times until the Qing.

Economic

organization

Lodges and guilds were occupational organizations organized by and for members (exam candidates, immigrants from a different province etc.) from the same native place in cities. They provided meeting space, lodging, financial aid, and storage facilities to merchants or travelers from their home region. Large lodges also had professional and religious facilities (a wharf, a temple). Guilds also organized workers, often in the fashion of secret societies.

Patronage

Networks outside of the local community organizations were scholarly communities which became increasingly strong political factions. Officials of the same examination year kept contact among themselves as well as with their teachers and examiners (in academies for instance).

Different

groups supported each other which in the end of the dynasty led to the development

of a competition between the state bureaucracy and the banners. Manchus,

Chinese bannermen, Northern Chinese and the

Portrait

of Emperor Kangxi

Portrait

of Emperor Kangxi

Portrait of Emperor Kangxi

(r. 1661-1722)

Portrait of Emperor Kangxi

(r. 1661-1722)

Emperor Yongzheng (r. 1723-1735)

Emperor Yongzheng (r. 1723-1735)

Portrait

of Emperor Qianlong (r. 1735-1796)

Portrait

of Emperor Qianlong (r. 1735-1796)