Introduction

For the second part of this week's lecture presentation we will address

the more philsophical questions posed in the Photography Theory section (found in the Photography: Part One lecture) throughout the sections of photographs below. To review these questions:

Again consider how all of this creates a much more complex dynamic of representing the reality around us with our photographic compositions. Such as think about how something like film speed changes the look of a photograph from the Vietnam War, is the photographic lighter or darker than what the human eye actually saw at the time?

Does this then change the narrative and thematic subject matter of the photograph?

Say for instance, even if the photographer was not "taking sides," can the photographer's use of of a lens and film speed create an anti-war or pro-war visual narrative? Is this more due to the photographer's use of the mechanics of the camera or is more due to the viewer's reading of the photographic composition?

Finally do we still find these situations, and questions, to be part of photography in our current times? Why or why not?

Interesting questions arise from this analysis: This photograph utilizes

elements of design and photography in what seems to be a formalized way, but

the photograph's subject matter conveys a single moment frozen in time.

How

did these elements occur in a photograph that was of a moment in reality (as

opposed to creating the scene in a studio)?

How much "staging" did occur of

this image? This this compositional and use of elements of design/photography "staging" create a true or false representation of the scene (and indeed of the historical context and moment)?

-

Does photojournalism reflect more of an aesthetic or narrative function

in art, or is it a combination of both?

-

How do the "Institutional Frames" change the meaning of

a photograph?

-

How do photographs of events and/or people define a culture?

-

What is the role of the photojournalist/photographer?

-

What is the role of the viewer?

-

The "artistic 'aesthetic' is seen as intentional" and canonized,

is this true of photojournalism?

-

Do the definitions of 'beauty' hurt or help photojournalism? Why?

-

What does defining a highly culturally sensitive and politicized form,

such as photojournalism, as art mean for the art administrator?

Learning Objectives and Reflection Framework

At the end of this presentation you will know more about:

-

The ways in which photography has a strong historical context that interplays with the elements of design/photography to create striking visual narratives.

-

The questions about how photographs are taken and what is the balance between the rational and intuitive processing of the photographer in creating photographic compositions?

-

The issue of 'beautification' in photojournalism and photographic compositions.

-

The ways in which photographic narratives can be the same, and different, across historical timeframes and cultures.

-

How photography is connected to your own lives, as both historical and creative documents.

-

Ways in which you can think about as possible arts administrators the challenges of presenting photographic works in artistic venues.

-

How in general, and specifically, you personally view and define the information found within photographic compositions.

Photography, Theories of Art, and Cultural Narratives

Art history of the early and mid 20th century argued that photography

was not part of the fine arts. As we moved into the modern and postmodern

art movements, art history acknowledged that photography was indeed

an art form of high regard. Museums of fine arts started to, on a regular

basis, exhibit and collect photographs as fine art.

This photography was associated with individuals who identified themselves

as artists, or at least went out of their way to create aesthetically

pleasing works. Photojournalism, on the other hand, was and has been

seen as a documentary forum (such as those Civil War photographs found in the Photography: Part One lecture). Photojournalists were/are out to document reality,

not create artistic narrative and aesthetics. But, in current times,

this has been reevaluated (just as photography in general was earlier).

Artistically created narrative is important in defining art, and can

be read into journalistic images, as well as the use of elements of

design and photography. These are all aspects that artists use to create

visually pleasing works. But where does documentation and creating art begin and end? Where is the overlap of each aspect? Think about this even further and the ways in which artistically produced works, such as Ansel Adams landscapes, also have aspects of artistic narrative and aesthetics and document our world and history.

Ansel Adams

Minarets, Evening Clouds, California

c. 1937

©The Trustees of the Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust

|

| |

Section One: For this section we are going to play a 'game' of

sorts. Take out a scratch piece of paper. Then look at each photograph

separately (going from the first to the second to the third). Write

down your first impressions of:

1) WHERE the photograph takes place.

2) WHEN the photograph takes place.

DO NOT THINK ABOUT THE QUESTIONS as you look at the photograph; just

go with your very FIRST IMPRESSION, which you will share in this week's Blog Topic Discussion. The answers are at the bottom of

the page (click on the link below the photographs).

|

|

|

Photography, especially photojournalism, is seen as a representation

of reality. We are taught to view photographs as the indexical signs

we learned about in the semiotics lecture. The photograph is seen as

a visual proof of an event. But, as we saw in the pyramid model 'Cultural

Baggage' is very important to viewing a photograph. In addition, The

Period Eye and Institutional Frames theories argue that the time

period in which we view an image in is very important to the way we

define that image's narrative.

|

| |

Section Two: This single photograph was taken during the Tiananmen

Square uprising and massacre of 1989. It is an excellent example of

the use of design and photographic elements to create a visually stunning

image. Note the use of visual vectors and the manner in which these

vectors create a tension within the overall frame. The tanks are pointed

downwards in one direction and the two on the bicycle are pointed in

the opposite direction. There is an interesting use of contrast with

the massive shapes (tanks and concrete) at the top of the frame, and

the bicycle is coming out of the dark empty space on the bottom. This

creates a juxtaposition of where we would think the heavy (foundation) elements

and lighter elements would be placed, and again creates a very dynamic

(oppressive) tension that relates to the story being told. A question arises out

of Williams' assertion that photography is a highly intuitive process.

This photograph would seem to be very spontaneous in that the scene

does not lend itself to lots of thought about how to create the composition.

But at the same time there is a very strong compositional frame that

utilizes elements of design. So, how much of this photograph is rationally

or intuitively thought out?

|

|

|

Section Three: This series of photographs is an example of what

I see as the 'beautification' problem of photojournalism. The issue

of 'beautification' arises when one defines photojournalism as an art

form. By using elements of design and photography to create memorable

images creates a dilemma of portraying horrific events in a beautiful

way. The first photograph below is straightforward in this aspect in

that it does not portray a horrific event. It is a photograph of a laser

beam reflected off the Washington Monument for a celebration. The photographer

utilized dynamic color and contrast to produce a visually pleasing photograph.

In this case it is an event meant to be beautiful.

The next is the infamous Hindenburg Disaster on May 6, 1937, where 35

passengers and crew died in an accident that was caught on film. Now

we have gone from the harmless narrative of the first photograph to

a photograph that captures the moment of the death of 35 humans. But,

if we can step away from the narrative and only look at the aesthetics

of the image, it is in its own right a beautifully portrayed photographic

image. It is very visually dynamic with an excellent exposure and lots

of striking light and dark contrast.

The last photograph is by a Russian (Soviet at the time) photographer

during the Second World War. It is a stunning photograph, especially

when one goes back to the elements of photography and examines how difficult,

using older technology, it would be to take this clear of an image with

the right exposure. And how the incoming shells and explosions from the turrets creates this fireworks look to the overall composition. But, what happens when one examines the narrative of this tank

battle that took place near Kursk on July 4, 1943, where over 6,000 German

and Russian tanks took part in the battle? The battle lasted over a

week, "by July 12 the battlefield was a hideous desert, not a tree

or bush left standing, with hundreds of burnt-out tanks, crashed planes,

and half-buried corpses littered the bare earth-the worst military carnage

in World War II" (Von Laue, T., Von Laue, A. (1996). Faces of a

nation: The rise and fall of the Soviet Union, 1917-1991. Golden, CO:

Fulcrum Publishing. p. 82.).

The issue arises about whether or not the

visual beauty of the photograph undercuts the horrific message it is portraying.

Take for instance Susan Sontag’s comments from her excellent book Regarding the Pain of Others:

“That a gory battlescape could be beautiful—in the sublime or awesome or tragic register of the beautiful—is a commonplace about images of war made by artists” (p. 75).

“One can feel obliged to look at photographs that record great cruelties and crimes. One should feel obliged to think about what it means to look at them, about the capacity actually to assimilate what they show. Not all reactions to these pictures are under the supervision of reason and conscience. Most depictions of tormented, mutilated bodies do arouse a prurient interest….All images that display the violation of an attractive body are, to a certain degree, pornographic. But images of the repulsive can also allure” (p. 95).

“No moral charge attaches to the representation of these cruelties. Just provocation: can you look at this? There is the satisfaction of being able to look at the image without flinching. There is the pleasure of flinching” (p. 41).

|

|

|

Section Four: Cultural narratives do share similarities across

time and society. This series of photograph documents the way in which

common threads can be seen in the subject matter. At the same time,

it is important to keep in mind the historical context of each image

and the way this context defines the story for particular viewers in

different cultures. Think about how one would view the series below

as a Chinese from Mainland China, or a Taiwanese, or a German, or a

Polish Jew, or an American, or a Vietnamese. Additionally, think about

how important these images would be at the time in creating a cultural

story.

The first is of German soldiers executing Polish Jews in the mid to

late 1930s, the second is Chinese Nationalists executing Chinese Communists

in 1949, and the third is the South Vietnamese solider executing a North

Vietnamese.

|

|

|

Section Five: Next, I have put together a series of photographs

that show how photography can portray different aspects of an issue

to create an overall cultural narrative. The first photograph is of

New Yorkers protesting a proposed Gay Rights Bill, the second is an

AIDS patient, and the third is of an AIDS patient who has died with

his loved ones at his bedside.

Take a look at this series and ask yourself:

-

How much does the imagery around us define who we are?

-

What is the artist's, photographer's, photojournalist's responsibility

in presenting cultural narrative?

-

How much has the meaning of the individual photographs changed

in this Institutional frame of an instructor placing the photographs

in a series for an academic lesson?

"Photographers often want to communicate a thought or emotion with their work. Although the camera lens views the world impartially, the photographer constantly judges, deciding what to photograph and how to photograph it -- focusing on creating a strong image that will communicate the desired message. The words that accompany a photograph may also influence the way we "read" the picture." (Library of Congress, Does The Camera Ever Lie? Retrieved July 1, 2005 from http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/cwphtml/cwpcam/cwcam1.html)

|

|

|

Section Six: The last question I want to address is the role of the arts administrator

in presenting art works, such as photographs, in certain venues. About

eight years ago I saw the photographs of Dmitri Baltermants (the tank

battle photograph above and the examples below) in a Portland gallery.

It was in a very interesting experience for me. Here were these large

and beautiful images of death and destruction hanging on a gallery wall

for sale. The first thing I thought to myself who would buy these for their home. A

lot of the prints would completely fill one's wall with dead bodies

or bombed out cities. But I thought about it more and decided on a better question: Were the prints only meant to go to museums? This question, along with the overall experience, brought up the issue of whether

or not exhibiting these types of images in any forum (gallery, museum,

library, etc.) would glamorize war and death. Personally, I was drawn

to the beauty and repelled by the grimness, and now as an arts administrator

in the museum field I wonder how to create a dialogue with visitors

that can address both the beauty and horror. It is a question that is

also very important to visual literacy theory.

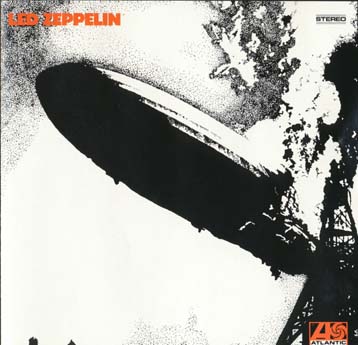

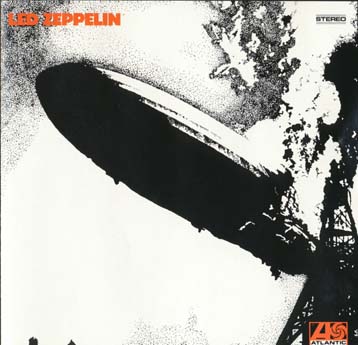

Another layer to this issue is how popular media utilizes images of death and destruction. So, when we recoil at the thought of putting the war images I saw in the gallery in one's home think about how images, such as the one below from the cover of Led Zeppelin's first album, adorn our walls.

|

|

|

Section One Answers:

Photograph One = Photographer not credited. Washington DC, USA

(1968). Hulton Getty Picture Collection. (This was after the riots that

followed the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr.)

Photograph Two = Photographer not credited. Internment camp, USA

(1945). Hulton Getty Picture Collection. (Japanese internment camp in the United States during

the Second World War)

Photograph Three = Michael McInerney. County Cork, Ireland.

(1933). RTE.

Back to Top

|