The ‘Totally

Irresistible’ CosmoGIRL: Narratives of Difference and Desire

Michele Clay

Operation Kiss Off:

Only a Smooch From a CosmoGIRL! Can Save Our Planet. Pucker up!

- from a link to a game on

the CosmoGIRL! Website

Get Inspired. See

Your Stylist.

- Redken ad

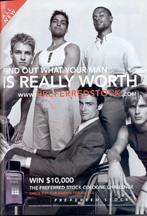

Find Out What Your

Man is Really Worth. The Preferred Stock Cologne Challenge.

-

preferredstock.com ad

CosmoGIRL! Magazine (CG), the little sister to Cosmopolitan, proclaims itself as ‘the teenage girl's new best friend and confidant’. Adolescence is a border full of richness and possibility. Borders are places to try new roles and scripts, but borders can also be dangerous. Friends and mentors help forge a smooth border crossing. Yet there is little advice in CG about navigating this crossing. CG constructs a reality based on mixed messages. The CosmoGIRL! is not just sexy, assertive, and fun, but she also wants power and success. However success in the Cosmo world entails being both sexy and a good consumer. In addition, the glamour and sexiness narrative subverts the necessary discussion of women’s sexuality. CG makes one feel included, until one realizes that inclusion requires ‘following the script’. Though the cover of CG suggests there are ‘685 Ways To Be Totally Irresistible’, these ‘ways’ still fall into a narrow definition of ‘irresistible’. This asserts hegemonic notions of how a young woman should negotiate her sexuality and identity in a complex world.

According to Chatman, the discourse is revealed both by looking at how the media is constructed and how it is meant to be read. CG is a light and playful fashion magazine for teenage girls. The design integrates advertising, advice, and fashion. Reading this magazine is meant to a fun and light task; one is not supposed to take CG seriously. What follows is an attempt to take CG seriously.

The Hearst Corporation owns CG. They also own numerous magazines, newspapers, and commercial websites. According to the Hearst Corporation website all of the board members and executives are male, except for one woman. Similar to the Hearst corporate discourse, there are limited scripts for women presented in CG. There are also a limited number of subject positions. Like many fashion magazines for women the emphasis is on the male subject position. This asserts the importance of women ‘appearing’ for men. When ads in CG have female subject positions, they are either acne sufferers or sexual servants (see page 23).

CG magazine constructs a particular assertion of truth and reality. This is evident when one tries to unpack the CosmoGIRL. Though many versions are offered up; her scripts are limited. She is concerned with fashion and looks (more than smarts). She wants power, but this is silently seceded to competition for male attention. She also loves celebrities and is encouraged to emulate them. She is all-American (white). Everyone else tries to spoil CosmoGIRL’s fun: black girls are flirty, boys hurt you, and parents get on your nerves.

The cover of CG does not feature the plunging necklines of Cosmopolitan; instead, Katie Holmes graces the cover in modest clothing. Her gaze is seductive, but who is Katie seducing? This seductive gaze appears in many images of women. Young readers internalize this gaze and seeing it feels natural. The abundance of these seductive images creates a hegemonic discourse of femininity. This enforces the myth of the perfect woman from the male gaze. Although there are many types of women, only one type is a ‘truthful’ representation (white, sexy, and fun). The subject-position in this magazine is the male. The ads, the stories, and the advice columns all work in concert. Inter-textuality is also evident in representations of women that mimic images found in pornography.

Advertising makes up a significant portion of CG (79 pages). Advertisements are also found within the regular features and columns (not included it the tally above). Often the lines blur between story and advertisement. For example, the ad on the back of CG mimics the cover: same pose, wind blowing through the hair, necklace and gaze. The ad suggests that being a cover girl requires CoverGirl make up. Both ads and articles in CG represent the good life: play, parties, and clubbing. Advertisers in the magazine also appear in the pages of columns and features. Girls are told how to ‘getta date’ (page 54) by buying gifts like Twister or cell phones for guys they want to date. Each product signifies a message to the potential suitor. Indeed securing the perfect boyfriend is a by-product of being the ‘perfect’ consumer.

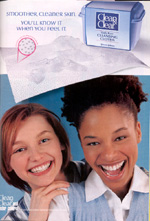

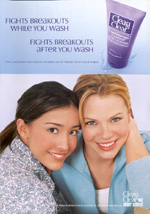

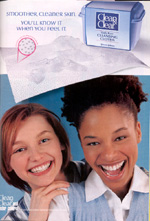

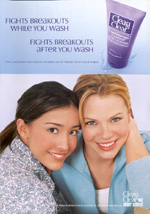

The ‘irresistible’ CosmoGIRL constructs her identity by establishing difference. In the Cosmo world there are many ‘others’. There are few images of anyone older than twenty. There are no images of families. When black or Asian women do appear, they are ‘sidekicks’ to young white women. Power circulates in these representations of difference. For example, there are three ads (pages 10, 95, and 183) with essentially the same pose: a white girl is ‘presenting’ her ‘ethnic’ friend. The white model either appears higher in the ad or she has her hands on her ‘friend’. These give the white models power and subjectivity; the ‘other’ is objectified as a decorative object. The copy underneath two of the ads read "Clean, Clear and Under Control" (pages 95 and 183). Clearly, not only pimples must be kept ‘clean and under control’.

Difference is also ambivalent because it can be both positive and negative. According to Hall, marking difference is powerful, because it represents taboo. This type of difference becomes alluring and exotic. The commodification of exotic women allows girls to fantasize about their own (subversive) sensuality. This conflicts with the dominant CG narrative: one must succeed and will not let her sensuality get in her way. She can assume the signifiers of sensuality by wearing exotic clothing and scents (J-Lo’s Glow, for example). The CosmoGIRL exists as a fantasy of male sexual desire.

Another example of the ‘other’ in CG is boys. For example in the ‘His Diary’ section (page 58), Steve visits Miami University to show CG readers what college is really like. Steve is curious about this school because Playboy ranked it second in colleges having ‘the hottest girls’. This story also provides another narrative: what do guys think of girls? This narrative also connects to a larger discourse of hegemonic ideologies of how women should behave.

However,

boys are also dissected, analyzed and rated. Boys in CG are judged by their

looks, clothes and net worth. One example is a regular feature, ‘the boy-o-meter’

(page 50). Another example is the Preferred Stock ad (page 53) asking

the reader to ‘Find Out What Your Man Is Really Worth’. This ad presents

three white men and two minorities. The occupations of each man are explicitly

coded: ‘ethnic’ men are either soldiers or laborers, and white men

are jocks, artists or executives. Each stereotype is heightened by their pose

and props. Hall suggests that stereotyping occurs "where there are gross

inequalities of power" (p. 258). The man in the center who is seated quite

comfortably is the white man in a suit. Clearly he is the ‘preferred stock’.

His power is both formed by his placement near ‘others’, and through

trangressive attributes gained in association with ‘others’. This,

according to Hall and Foucault, is the circulation of power through stereotype

and difference.

However,

boys are also dissected, analyzed and rated. Boys in CG are judged by their

looks, clothes and net worth. One example is a regular feature, ‘the boy-o-meter’

(page 50). Another example is the Preferred Stock ad (page 53) asking

the reader to ‘Find Out What Your Man Is Really Worth’. This ad presents

three white men and two minorities. The occupations of each man are explicitly

coded: ‘ethnic’ men are either soldiers or laborers, and white men

are jocks, artists or executives. Each stereotype is heightened by their pose

and props. Hall suggests that stereotyping occurs "where there are gross

inequalities of power" (p. 258). The man in the center who is seated quite

comfortably is the white man in a suit. Clearly he is the ‘preferred stock’.

His power is both formed by his placement near ‘others’, and through

trangressive attributes gained in association with ‘others’. This,

according to Hall and Foucault, is the circulation of power through stereotype

and difference.

There are also examples of boys as

a predatory ‘other.’ These are especially interesting in the way that

they work with the dominant narrative of CG. CosmoGIRL’s sexuality is for

men only. Ads in CG tend to accentuate risky behavior. But the male gaze in

CG is not always friendly and a little risk crosses the line into ‘dangerous’.

For example in a Levi’s ‘too super-low boot-cut jeans’

ad (page 15), the copy reads: ‘Dangerously Low’. The model is alone in an empty parking lot and

it is dark and desolate. She looks like she may have been crying and appears

defeated. She strikes a ‘tough pose’, but her appearance betrays her

toughness. There is someone else in this ad, but they are not visible. Low jeans

are currently fashionable, but if jeans are dangerously low–does

this signify a potential rape? The model is in danger, but who is threatening

her?

‘Dangerously Low’. The model is alone in an empty parking lot and

it is dark and desolate. She looks like she may have been crying and appears

defeated. She strikes a ‘tough pose’, but her appearance betrays her

toughness. There is someone else in this ad, but they are not visible. Low jeans

are currently fashionable, but if jeans are dangerously low–does

this signify a potential rape? The model is in danger, but who is threatening

her?

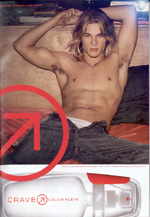

Another

example of risk is a Calvin Klein Crave ad (page 23). This ad features

a sexy, enticing, and Adonis-like model. A quick glance at such a specimen offers

the eye some relief in a magazine brimming with fetishized images of women.

Unfortunately, a second glance detonates another narrative. The model leans

back with his pants unzipped, pulled down, and open. His underwear is visible.

His hands do not reach out to the female viewer. He is not here to provide her

pleasure or fulfill her fantasy. His hands are behind his head, ready for fellatio.

If his pose is not suggestive enough, the phallic perfume bottle and the red

arrow assist the imagination. This ad is also an example of inter-textuality.

The holiday issue Cosmopolitan (CG’s older sister) featured an article

on ‘how to surprise him with fellatio tricks’. In ‘adult’

Cosmo the message is explicit and fun, whereas the little sister’s

message is a little harder to read. The message is the same, if you want to

keep your man you better be good at ‘it’. This is not to assert that

there is anything wrong with sex, but that there are few representations of

women’s pleasure, let alone examples of dialogue and reciprocity between

partners.

Another

example of risk is a Calvin Klein Crave ad (page 23). This ad features

a sexy, enticing, and Adonis-like model. A quick glance at such a specimen offers

the eye some relief in a magazine brimming with fetishized images of women.

Unfortunately, a second glance detonates another narrative. The model leans

back with his pants unzipped, pulled down, and open. His underwear is visible.

His hands do not reach out to the female viewer. He is not here to provide her

pleasure or fulfill her fantasy. His hands are behind his head, ready for fellatio.

If his pose is not suggestive enough, the phallic perfume bottle and the red

arrow assist the imagination. This ad is also an example of inter-textuality.

The holiday issue Cosmopolitan (CG’s older sister) featured an article

on ‘how to surprise him with fellatio tricks’. In ‘adult’

Cosmo the message is explicit and fun, whereas the little sister’s

message is a little harder to read. The message is the same, if you want to

keep your man you better be good at ‘it’. This is not to assert that

there is anything wrong with sex, but that there are few representations of

women’s pleasure, let alone examples of dialogue and reciprocity between

partners.

Another example appears in the Issues section. This is a story about a cheerleader who was sexually assaulted by her coach. Included in this story is a section warning: "Is an Adult in Your Life a Predator?" This story seems to suggest that only adults are predators (thus ignoring date rape). The only hotline number included is the 24-hour national child abuse hotline. This story involved not only child abuse, but also sexual harassment, coercion, and rape. Since many readers (evidenced in other sections) are in their twenties, the writers should have included more hotline numbers. What is ironic is that the ‘predator’ is criticized for suggesting the cheerleaders wear sexy clothes. But the outfits reveal (and suggest) a lot less than the clothing featured in CG. It is irresponsible for CG to dress the reader in sexy outfits and poses, without providing advice on how to negotiate boundaries or unwanted attention. CG doesn’t explicitly define what unwanted attention is. Finally, the story also makes light of the betrayal and trauma these women are trying to reconcile.

So is CG really ‘a teenage girl’s best friend’? CG does not have the qualities of a good friend. Many pages are dedicated to hyper-representations of sexiness, power and looks. This is the kind of ‘friend’ that invites you to a costume party; upon arrival you are the only one in costume (a sexy one) and all of the guests are men! Friends in the CG world have connections, throw cool parties, and compete for boys. CG ignores the discussion of issues such as building confidence, friendships or community. Features such as ‘Boost Your Confidence With Astrology Today’ assert that confidence is best left to fate, not from participating in activities such as social justice, debate team or sports.

In summary, this magazine perpetuates the representation of women as objects. Stereotypes appear on many interconnected levels in CG, making it difficult to negotiate mixed messages. This stereotyping asserts what Foucault calls power/knowledge. Power both produces and limits representations and narratives in CG. This power circulates through the dominant narratives and images of the ‘other’. This magazine may appear to promote playfully subversive roles for women, but in the end, the dominant hegemonic narrative of male sexual fantasy creates the norm. Women can succeed, but only in certain ways and in terms defined by this fantasy. Certainly teenage girls deserve much better friends and confidants.