CosmoGIRL!: A

Trojan Horse for Advertisers

Corinne Johnson

CosmoGIRL!, a teen spin-off of the

successful women’s magazine Cosmopolitan, is published by the Hearst

Corporation, one of the world’s largest magazine publishers, which also

owns such well-known and diverse titles as Esquire, Good Housekeeping, Popular

Mechanics, Town & Country, and O, The Oprah Magazine. The high-gloss

monthly appears to be targeted at middleclass girls of all ethnicities in their

early teens. This deduction is based on observations that: the merchandise advertised

is mostly at department store prices; women of color are well represented and

appear no more exoticized than others (see pp. 111, 114, 164-165, 172-173, 174-177);

and the editorial is a "pajama party" mixture of pop star profiles,

personality quizzes, and "sneak peeks" at college life and other people’s

diaries.

My critique of CosmoGIRL! focuses on

the kind of discourse it creates about what it means to be a girl, and why it

might choose to be this particular type of role model. I look at the magazine’s

juxtaposition of feminine and masculine, and how it uses stereotyping to both

establish men as the "other" and propagate a culture of insecurity

that serves to further the publisher’s financial goals. While there is

clear evidence of parents also being constructed as "other" (pp. 164),

this is a separate argument and, for brevity’s sake, I don’t go there.

CosmoGIRL! attempts to represent itself

as something more than just another girls’ fashion magazine. By showcasing

successful females (see "Project 2024," p. 106, and "Cosmo Girl

of the Year Awards," pp. 124-137) and including self-help sections such

as "Girl Talk" and "Life Coach," the magazine tries to center

itself in a discourse that promotes female self-esteem, self-acceptance, and

empowerment. In her editor’s letter (page 28), Rubenstein tells readers

not to worry if they don’t fit the mold others create for them — to

be their own person, "the girl you’ve always wanted to be." But

then the magazine proceeds to tell readers that the girl they want to be is

thin ("Fitness 101," pp 96-99), fashionably dressed and heavily made

up, with chemically colored and styled hair. Unfortunately, the bulk of CosmoGIRL!’s

editorial conspires with its abundant ads for sexy clothes, sexy fragrances,

and sexy new shades of makeup, to create an inter-textual discourse that is

anything but unique.

CosmoGIRL!, I found, is just another

voice for the same tune sung by most women’s magazines — a discourse

that establishes a female’s ultimate concern as that of making herself

attractive to males. The magazine makes no mention of current news events. Indeed,

it contains little editorial of substance. The majority of its content is structured

around beauty, fashion, and dating tips and the merchandise to capitalize on

these "important insights." The lead cover story of the issue I critiqued

is "685 Ways to Be Totally Irresistible."

In CosmoGIRL!’s teen-female version

of Jhally’s "Dreamworld," the hegemony of male/female binary

opposition is reversed. Here, girls hold the powerful subject position of spectator

and it is men who are the objectified "other," reduced to a handful

of characteristics or mere body parts. On page 50, for example, is a "Boy-O-Meter"

where readers are invited to evaluate the featured fellow, on a scale from "sizzle"

to "fizzle," based solely on a photograph.

Men are stereotyped as either guileless

and devoted prey waiting to be snared, or jerks and sexual predators. A good

example of this binary form of representation is the "Date Your Crush"

feature on page 139. The same boy who "means everything to you" becomes

"your stanky crush" if he doesn’t return your affections. Worthwhile

men, the magazine suggests, are more interested in a girl’s personality

than her physical appearance and are willing to make a romantic commitment.

Faithful 18-year-old Stephen (p. 58), for example, states in his travel diary

that thinking of his girlfriend back home saved him from making "some stupid

decisions" where other girls were concerned. And the magazine’s 27-year-old

centerfold maintains that the first thing he notices about a girl is "the

way she carries herself" (69). This hunk of pretty male flesh also confesses

that one of his lifelong dreams is "to be a great father."

Even though the men objectified by

CosmoGIRL! are typically older than its readers (i.e. forbidden and exciting

"college guys"), within the magazine’s regime of representation

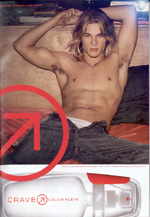

they are vulnerable and, therefore, controllable. The Calvin Klein cologne ad

on page 23 is a good example of this myth under construction. Denotatively,

we have a photograph of a shirtless  young

man sitting on a sofa with his pants unzipped. But such signifiers as the model’s

unzipped pants and slouching posture — emphasized by the low camera angle,

which positions the reader below and between his legs — conveys the message

that this person is surrendering himself to the viewer’s sexual exploitation.

His half-closed eyes and his arms laid back behind his head imply total submissiveness.

young

man sitting on a sofa with his pants unzipped. But such signifiers as the model’s

unzipped pants and slouching posture — emphasized by the low camera angle,

which positions the reader below and between his legs — conveys the message

that this person is surrendering himself to the viewer’s sexual exploitation.

His half-closed eyes and his arms laid back behind his head imply total submissiveness.

Calvin Klein is counting on this culturally

understood "sign" combining with a second set of signifieds —

a romantic Western female ideology about the relationship of sex to romance

— to produce a whole new meaning for their ad through what Barthes terms

a "second level of signification" (Hall, 39). The play on words ("Get

it on," in tiny subscript below the photo) has apparently been thrown in

to assure that CosmoGIRL!’s young readers don’t miss the myth

being marketed here — that you, too, can have sex and love if you buy this

product.

Sex sells. And CosmoGIRL!, although

meant for young girls, is subtly sexual. Most men featured in the magazine are

either topless or have their shirt unbuttoned (see "Dear Almost Naked College

Guy," p. 112; the centerfold model, pp. 64-69;  and

the article on p. 59), suggesting that teen girls have — or should have

— a fetish for male chests. This amounts to little more than an "age

appropriate" disavowal of an obsession with male genitalia, which allows

young girls to indulge in sexual fantasy even while their gaze is displaced

from the true object of fascination (Hall, 267). As unobserved onlookers, CosmoGIRL!’s

readers are safe to exercise a voyeuristic power to reduce the male "other"

to an erotic "thing" to be consumed.

and

the article on p. 59), suggesting that teen girls have — or should have

— a fetish for male chests. This amounts to little more than an "age

appropriate" disavowal of an obsession with male genitalia, which allows

young girls to indulge in sexual fantasy even while their gaze is displaced

from the true object of fascination (Hall, 267). As unobserved onlookers, CosmoGIRL!’s

readers are safe to exercise a voyeuristic power to reduce the male "other"

to an erotic "thing" to be consumed.

What

is interesting, considering that CosmoGIRL! purports to champion female

individuality and empowerment, is that girls also fall victim to symbolic violence

within its pages. All of the female images in the magazine are stereotypically

thin, suggestively dressed, and heavily made up. Overall, the inter-textual

meaning produced by CosmoGIRL! is that females are incomplete without

a man in their life and, therefore, girls need to make whatever physical changes

are necessary to lure and capture a boyfriend.

What

is interesting, considering that CosmoGIRL! purports to champion female

individuality and empowerment, is that girls also fall victim to symbolic violence

within its pages. All of the female images in the magazine are stereotypically

thin, suggestively dressed, and heavily made up. Overall, the inter-textual

meaning produced by CosmoGIRL! is that females are incomplete without

a man in their life and, therefore, girls need to make whatever physical changes

are necessary to lure and capture a boyfriend.

This discourse also implies that the only

things men are interested in are a woman’s physical attributes, a statement

in direct contrast to the "sensitive man" fantasy being promoted by

the magazine on its surface. Both guys and girls have been naturalized to the

state of animals in pursuit of a mate, attracted by scent and/or a show of finery.

This discursive formation creates a deficit self-image that serves the publisher

well. Commercial interests — and the magazines that are dependent upon

their advertising income — are working hard to expand and reinforce a culture

of insecurity that trusts in consumerism as therapy.

According to her profile on the corporation’s

website, one of the main focuses of Hearst Magazine’s president, Cathleen

Black, is the extension of the company’s titles into other commercial products.

CosmoGIRL!, launched in late 1999 — just as the magazine

industry was catching on to the long-term benefits of establishing name brand

recognition in the teenaged consumer set - is one of these product extensions.

Through their diversified interests in magazines,

television, radio, syndicated production, and cable stations and networks, media

moguls like the Hearst Corporation have access to a powerful array of tools

of enculturation. They pretty much control the way televised and print media

represent the world. It is only through educating people to the manipulation

of psyche taking place that there lies any hope of dismantling this reductionist

system of representation that encourages mass psychosis in the interest of commercial

gain.

young

man sitting on a sofa with his pants unzipped. But such signifiers as the model’s

unzipped pants and slouching posture — emphasized by the low camera angle,

which positions the reader below and between his legs — conveys the message

that this person is surrendering himself to the viewer’s sexual exploitation.

His half-closed eyes and his arms laid back behind his head imply total submissiveness.

young

man sitting on a sofa with his pants unzipped. But such signifiers as the model’s

unzipped pants and slouching posture — emphasized by the low camera angle,

which positions the reader below and between his legs — conveys the message

that this person is surrendering himself to the viewer’s sexual exploitation.

His half-closed eyes and his arms laid back behind his head imply total submissiveness. and

the article on p. 59), suggesting that teen girls have — or should have

— a fetish for male chests. This amounts to little more than an "age

appropriate" disavowal of an obsession with male genitalia, which allows

young girls to indulge in sexual fantasy even while their gaze is displaced

from the true object of fascination (Hall, 267). As unobserved onlookers, CosmoGIRL!’s

readers are safe to exercise a voyeuristic power to reduce the male "other"

to an erotic "thing" to be consumed.

and

the article on p. 59), suggesting that teen girls have — or should have

— a fetish for male chests. This amounts to little more than an "age

appropriate" disavowal of an obsession with male genitalia, which allows

young girls to indulge in sexual fantasy even while their gaze is displaced

from the true object of fascination (Hall, 267). As unobserved onlookers, CosmoGIRL!’s

readers are safe to exercise a voyeuristic power to reduce the male "other"

to an erotic "thing" to be consumed. What

is interesting, considering that CosmoGIRL! purports to champion female

individuality and empowerment, is that girls also fall victim to symbolic violence

within its pages. All of the female images in the magazine are stereotypically

thin, suggestively dressed, and heavily made up. Overall, the inter-textual

meaning produced by CosmoGIRL! is that females are incomplete without

a man in their life and, therefore, girls need to make whatever physical changes

are necessary to lure and capture a boyfriend.

What

is interesting, considering that CosmoGIRL! purports to champion female

individuality and empowerment, is that girls also fall victim to symbolic violence

within its pages. All of the female images in the magazine are stereotypically

thin, suggestively dressed, and heavily made up. Overall, the inter-textual

meaning produced by CosmoGIRL! is that females are incomplete without

a man in their life and, therefore, girls need to make whatever physical changes

are necessary to lure and capture a boyfriend.