Recognizing the experience can help heal patients and repair institutional damage, they write in the American Psychologist

EUGENE, Ore. — Sept. 15, 2014 — Clinical psychologists are being urged by two University of Oregon researchers to recognize the experiences of institutional betrayal so they can better treat their patients and respond in ways that help avoid or repair damaged trust when it occurs in their own institutions.

EUGENE, Ore. — Sept. 15, 2014 — Clinical psychologists are being urged by two University of Oregon researchers to recognize the experiences of institutional betrayal so they can better treat their patients and respond in ways that help avoid or repair damaged trust when it occurs in their own institutions.

The call to action for clinicians as well as researchers appears in a paper in the September issue of the American Psychologist, the leading journal of the American Psychological Association.

In their paper, UO doctoral student Carly P. Smith and psychology professor Jennifer J. Freyd draw from their own studies and diverse writings and research to provide a framework to help recognize patterns of institutional betrayal. The term, the authors wrote, aims to capture "the individual experiences of violations of trust and dependency perpetrated against any member of an institution in a way that does not necessarily arise from an individual's less-privileged identity."

AUDIO CLIPS from Carly Smith

► General overview of the paper, 46 seconds

► A framework for clinicians, 39 seconds

While their paper focuses on sexual assaults on college campuses, in the military and in religious institutions, the authors say that such betrayal is a wide-ranging phenomenon. Throughout the paper, they discuss the case of a college freshman in the Midwest whose questionably handled allegations against a major university's football player eventually contributed to her suicide.

"I think what struck me most in our examination of the literature was that people are starting to turn over this idea in their minds in all these different fields," Smith said. "They are starting to notice that when we see abuse or other trauma occurring, it might behoove us to broaden our focus beyond the individual level."

They note that institutional betrayal is a dimensional phenomenon, with acts of omission and commission as well as instances of betrayal that may vary on how clearly systemic they are at the outset. Institutional characteristics that the authors say often precede such betrayal include:

• Membership qualifications with inflexible requirements where "conformity is valued and deviance quickly corrected as a means of self-policing among members." Often, a member making an accusation faces reprisal because of the institutional value placed on membership.

• Prestige given to top leaders results in a power differential. In this case, allegations that are made by a member against a leader often are met by gatekeepers whose roles are designed to protect top-level authority.

• Priorities that result in "damage control" efforts designed to protect the overall reputation of the institution. Examples include the abuse scandal at Pennsylvania State University, the movement of clergy to other locations in the face of allegations and hiding incidents of incest within family units. More recently, Freyd and Smith noted, the NFL demonstrated this quality by denying it had seen video footage of one of its players battering his fiancee and its previously long record of minor penalties for such interpersonal abuse.

• Institutional denial in which members who allege abuse are marginalized by the institution as being bad apples whose personal behaviors should be the issue.

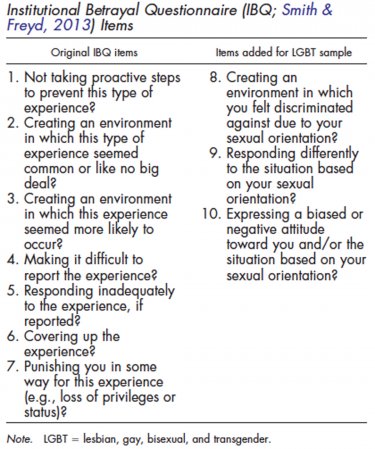

Smith and Freyd, in the paper, offer recommendations to institutions for reducing the likelihood of betrayal. Recognizing such patterns is also important for clinicians who work with people who have been sexually abused, Smith said. She and Freyd suggest the use of the Institutional Betrayal Questionnaire they developed for their research. The questionnaire — initially envisioned for use amid a rising number of sexual assaults being reported by women in the military — contains key terminology that might help both clients and clinicians discuss abuse.

Smith and Freyd, in the paper, offer recommendations to institutions for reducing the likelihood of betrayal. Recognizing such patterns is also important for clinicians who work with people who have been sexually abused, Smith said. She and Freyd suggest the use of the Institutional Betrayal Questionnaire they developed for their research. The questionnaire — initially envisioned for use amid a rising number of sexual assaults being reported by women in the military — contains key terminology that might help both clients and clinicians discuss abuse.

"Clinicians can take this knowledge and apply it directly into their practice," Smith said. "Just having the language can help them work with clients who may be grappling with a feeling of having been mistreated by the institution rather than helped and protected by it. In trauma work, language and developing a coherent narrative improves understanding of events that, at face value, are disorienting. It can help make sense of how events and the aftermath unfolded. This can help clinicians work with clients to make sense of their experience so that they can move forward with their lives."

It is important, Smith added, that clinicians also are aware of their own roles within institutions or in private practice. "It is important that clinicians be aware of the potential to act in a way that contributes to institutional betrayal," she said. "They can also contribute to healing and repairing the damaged trust that arises from institutional betrayal. We think this can have a ripple effect of healing for both the individual and the relationship with an institution."

Media Contact: Jim Barlow, director of science and research communications, 541-346-3481, jebarlow@uoregon.edu

Sources: Carly P. Smith, doctoral student, Department of Psychology, 541-346-5093, carlys@uoregon.edu, and Jennifer J. Freyd, professor of psychology, 541-346-4929, jjf@uoregon.edu

Note: The University of Oregon is equipped with an on-campus television studio with a point-of-origin Vyvx connection, which provides broadcast-quality video to networks worldwide via fiber optic network. In addition, there is video access to satellite uplink, and audio access to an ISDN codec for broadcast-quality radio interviews.