EUGENE, Ore. -- (April 27, 2011) -- Researchers at four institutions, using data gathered from the USArray seismic observatory, have seen more than 200 miles below the surface, capturing evidence on how the Colorado Plateau, including the Grand Canyon, formed and continues to change even today.

EUGENE, Ore. -- (April 27, 2011) -- Researchers at four institutions, using data gathered from the USArray seismic observatory, have seen more than 200 miles below the surface, capturing evidence on how the Colorado Plateau, including the Grand Canyon, formed and continues to change even today.

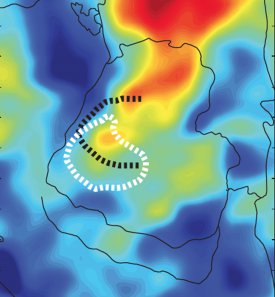

Reporting in the April 28 issue of the journal Nature, the eight-member team reports that uplift occurred as bottom portions of the lithosphere -- the upper layer of the Earth -- deteriorated, peeled and collapsed into magnetic, liquid-rich material, allowing the thick, underlying layer of fragile rock -- the asthenosphere -- to ascend and push up remaining surface material.

The images they created document the process of delamination. They also make a case for how much of the western half of the United States and, perhaps, many similar areas around the globe have formed, said co-author Eugene D. Humphreys, professor of geological sciences at the University of Oregon. The process is ongoing, he added, with the western half of the Grand Canyon still rising ever so slowly on the geological clock.

The images they created document the process of delamination. They also make a case for how much of the western half of the United States and, perhaps, many similar areas around the globe have formed, said co-author Eugene D. Humphreys, professor of geological sciences at the University of Oregon. The process is ongoing, he added, with the western half of the Grand Canyon still rising ever so slowly on the geological clock.

"This is the first time this process has actually been imaged, and it gives us insight into how tectonic plates can disintegrate and give surface uplift," Humphreys said.

|

Audio from Gene Humphreys: |

UO doctoral student Brandon M. Schmandt applied UO-developed tomography techniques, similar to those used in CAT scans, with USArray data collected by Rice University geologists, including lead author Alan Levander. Their computation was pulled together using interface imaging techniques developed by Levander.

Researchers, including scientists from the University of Southern California and the University of New Mexico, created depth maps of underground features. They did this by calculating seismic secondary waves (S waves) and primary waves (P waves), which travel differently in response to earthquakes anywhere in the world. These waves were monitored at the USArray stations, which were inserted into the ground throughout the west in 2004.

Much of the western United States rose upward in the absence of horizontal tectonics in which plates collide, forcing one to descend and the other to rise. The Colorado Plateau covers much of an area known as the Four Corners -- southwestern Colorado, northwestern New Mexico, northeastern Arizona and southeastern Utah.

Much of the western United States rose upward in the absence of horizontal tectonics in which plates collide, forcing one to descend and the other to rise. The Colorado Plateau covers much of an area known as the Four Corners -- southwestern Colorado, northwestern New Mexico, northeastern Arizona and southeastern Utah.

"Most geologists learned that vertical motions, like mountain building, are the result of horizontal motions such as thrust faulting, such as the Himalayas." Humphreys said. "More recently we are finding that changes in the density distribution beneath an area -- like the base of a relatively dense plate falling off -- can have a strong effect on surface uplift, too. This has been surprising to many, and for the base of a plate -- in this case, the lithosphere, in geology terminology -- falling off in particular, the question is: How does it do that?"

The two alternative theories have centered on a dripping process, or melting of the lithosphere's underside, or the peeling that occurs in delamination. In 2000, geologists argued that the Sierra Nevada mountain range is the result of the latter.

"We had to find a trigger to cause the lithosphere to become dense enough to fall off," Levander said. The partially molten asthenosphere is "hot and somewhat buoyant, and if there's a topographic gradient along the asthenosphere's upper surface, as there is under the Colorado Plateau, the asthenosphere will flow with it and undergo a small amount of decompression melting as it rises."

It melts enough, he said, to infiltrate the base of the lithosphere and solidify, "and it's at such a depth that it freezes as a dense phase. At some point, it exceeds the density of the asthenosphere underneath and starts to drip." The heat from the invading melts also reduces the viscosity of the mantle lithosphere.

It's possible, Humphreys said, that mountainous areas of southern and northern Africa and western Saudi Arabia resulted from the same process.

Co-authors with Levander, Schmandt and Humphreys were USC geologist Meghan Miller, Rice graduate student Kaijian Liu, Rice geologist Cin-Ty A. Lee, and geologist Karl E. Karlstrom and doctoral student Ryan Scott Crow, both of the University of New Mexico.

National Science Foundation EarthScope grants and the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation Research Prize to Levander funded the research.

About the University of Oregon

The University of Oregon is among the 108 institutions chosen from 4,633

U.S. universities for top-tier designation of "Very High Research

Activity" in the 2010 Carnegie Classification of Institutions of Higher

Education. The UO also is one of two Pacific Northwest members of the

Association of American Universities.

Media Contacts: Jim Barlow, director of science and research communications, 541-346-3481, jebarlow@uoregon.edu and Mike Williams, senior media relations specialist, Rice University, 713-348-6728, mikewilliams@rice.edu

Photos: Click on images to access original high-resolution versions. Also offered here: a mug shot of Eugene Humphreys

Source: Eugene Humphreys, professor of geological sciences, 541-346-5575, ghump@uoregon.edu; Alan Levande at Rice University may be reached through Mike Williamss (above).

UO Science on Facebook: http://www.facebook.com/UniversityOfOregonScience