|

|

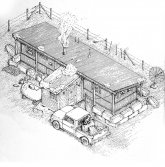

| Graphic captures Heath's theory that a building is not a place unless it incorporates people and how they use the space. | |

| (Image courtesy of Kingston Heath) |

EUGENE, Ore. -- (Dec. 13, 2008) -- A building designed to recapture the past may bring nostalgia, but the end product may not capture current realities of a place, says Kingston Heath, a professor of historic preservation at the University of Oregon.

"It is a humanistic inquiry that recognizes that buildings and settings, alone, do not make place," he said in a talk Dec. 13 at the 2008 annual meeting of the International Association for the Study of Traditional Environments in Oxford, UK. "People, in their interaction with the natural and built environment, make place."

Heath draws attention to a small group of architecture and urban design professionals who in recent years have begun to challenge the practice of designing modern structures that simply strive to produce mirages of the past. The emerging field is called "situated regionalism."

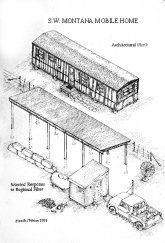

"This is a design-and-planning approach that considers the current human and environmental situation," Heath said in an interview before his talk. "We look at the regional filter -- the collective forces that shape place."

"This is a design-and-planning approach that considers the current human and environmental situation," Heath said in an interview before his talk. "We look at the regional filter -- the collective forces that shape place."

Heath's approach to the field will be more fully detailed in his upcoming book "Vernacular Architecture and Regional Design: Cultural Process and Environmental Response." His talk Saturday -- during the session "Regeneration and Tradition" chaired by UO architecture colleague Mark Gillem -- aimed to define vernacular architecture as a way to explore both current and past uses and needs of populations living in a particular place to better understand regional dynamics.

Also speaking in the session was UO architecture professor Howard Davis, who focused on the relationship between craftsmanship and the possibility of contemporary production drawing upon traditional building practice with modern methods. His material, from a graduate seminar, also will be part of a book, currently titled "Post-Industrial Craftsmanship in Buildings and Cities."

Regionally based architecture, Heath said, should respond to very specific dynamics of local and extra-local forces, resulting in design and planning that uses data, not imagery, of how buildings and their uses have changed over time to create new buildings that people can use according to current needs. "The end result may or may not look like something in the past," Heath said, "but ultimately it will be situated in the current human condition."

In his talk, Heath notes that "no culture is monolithic." As people move into an area they establish their own approach to their existing needs. As time moves on, new people, perhaps coming with different cultural traditions and preferences move in, leading to changes to the way existing buildings are used. Environmental conditions may change, along with new technologies and new ways of social approaches to building use. "Hybridity results," he said.

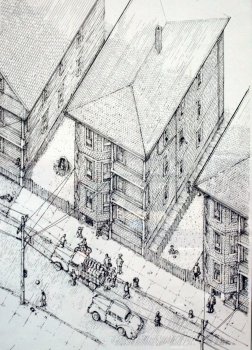

Vernacular, or regional, architecture is always in transition, not locked in the historical past, Heath said. "The regional filter that once identified the past may have changed for various reasons. Rather than looking at patterns of continuity, we need to be studying patterns of contradiction that show how past forms are being altered to meet the needs of people that haven't been accommodated in design. They may be visually awkward, even unattractive."

In effect, architects and planners should serve as "a kind of therapist who listens and sees a built environment in all of its messiness," he said, adding that idea is the same as turning emotional chaos into effective accommodation. "Architects and planners can look at this physical chaos of buildings in transition and give the chaos some conceptual and formal clarity that addresses current needs, opportunities, and aspirations."

His book will elaborate this approach to regional architecture through nine international case studies that address various approaches to designing residences and public buildings.

"The overarching aspect of situated regionalism is that it is really oriented toward the next generation of architecture and urban design students who want to make a difference in the world," Heath said. "What we are looking at are examples -- some award-winning and others that are based on work by emerging young architects -- that provide insights into achieving positive social and environmental accommodation through design."