|

| UO biologist Bruce Bowerman points to images showing cell division |

| (Photo by Jim Barlow) |

EUGENE, Ore. -- (Dec. 4, 2008) -- Biologists have discovered a mechanism that is critical to cytokinesis -- nature's completion of mitosis, where a cell divides into two identical daughter cells.

The researchers have opened a new window on the assembly and activity of a ring of actin and myosin filaments that contract to pinch a cell at just the right time. They focused on key proteins whose roles drive signaling mechanisms that promote the production of both linear and branching microfilaments along the inside surface membrane of a dividing cell. By down-regulating the production of branched microfilaments at the right time, the membrane may be more malleable and better able to pinch inward and complete cytokinesis.

|

|

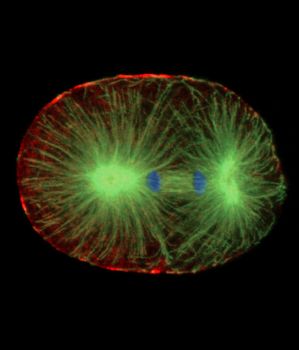

A photomicrograph made using fluorescent light microscopy shows a one-cell stage Caenorhabditis elegans (roundworm) embryo undergoing cell division. View this image and another with additional information. (Image courtesy of Bruce Bowerman) |

The findings-- detailed in the Dec.5 issue of the journal Science -- come from basic research using Caenorhabditis elegans (roundworm) embryos. The discovery provides more basic insight than immediate biomedical application, but the implications could lead to a fine-tuning of anti-cancer drug therapies or to isolating new targets for drugs to stop cancerous cell division, said Bruce Bowerman, professor of biology in the University of Oregon's Institute for Molecular Biology.

Bowerman and Karen Oegema of the Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research at the University of California, San Diego, were principal investigators of a seven-member team funded by the National Institutes of Health. Julie C. Canman, a former postdoctoral fellow in Bowerman's lab and now a postdoctoral fellow at the Ludwig Institute, was the study's lead author.

Scientists have theorized that modulation of microfilament structure plays a role in cell division. However, finding that such shape-shifting down-regulation specifically targets branched microfilaments assembly came as a surprise, Bowerman said.

C. elegans is used in many genetics research laboratories to discover basic requirements for the 20,000 genes that compose its genome; most of the genes are conserved in humans and carry out similar processes. Using these nematodes, Bowerman said, is allowing researchers to "find players inside that previously weren't known to be involved in cytokinesis."

The new research focused on enzymes targeted by the GAP domain of the protein CYK-4 that is part of a multi-protein complex called centralspindlin. This GAP domain functions as a GTPase activator, targeting protein switches called GTPases, which bind and hydrolyze guanosine triphosphate (GTP) to guanosine diphosphate (GDP). When GTPase is bound to GTP it acts as an on switch; when GTP is hydrolyzed to GDP, the switch is turned off.

The researchers found that deleting a GTPase called Rac could bypass the requirement for the GAP domain in CYK-4, Bowerman said. Because Rac GTPases promote branched microfilament assembly, this suggests that normally the CYK-4 GAP acts to down-regulate the production of branched microfilaments.

Previously CYK-4 had been thought to only down-regulate a different GTPase called RhoA, which promotes linear microfilament assembly. Thus these new results implicate the down-regulation of branched microfilaments at the cell cortex as a critical step in cell division.

"We have found a completely new way of thinking about how cells remodel their internal skeletons such that they undergo the shape changes needed to divide and produce daughter cells," Bowerman said. "Some of these proteins already are targets of some cancer drugs. Now we have the opportunity to study and understand how certain proteins stabilize microfilaments within cells and inhibit cell division, and how other proteins act to modulate the stiffness of a cell's membrane to allow them to undergo shape changes needed for cell division and proliferation."

Co-authors with Bowerman, Oegema and Canman were Lindsey Lewellyn, Kimberley Laband and Arshad Desai, all of the Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research, and Stephen J. Smerdon of the National Institute for Medical Research.