Week

4: Europe and the World

Textbook reading: Birn, Chapter 5. This

week we look at Europe's relations with the wider world from two perspectives:

first, the growing impact of European commercial and (increasingly)

political and military penetration of the societies in Asia and Africa;

and second, the reverse effects of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century

"globalization" on European economies and cultures.

The First

Globalization

I. Expanding Horizons: The Advance

of European Explorations

Image right: Willem van de Velde (1633-1707), The

Cannon Shot (Detail) (1670). Oil on canvas, 78,5 x 67

cm. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam. Image Source: Web

Gallery of Art.

Map: European Explorations (1492-1600)

Map: The Fifteenth-Century Eurasian World System

Map: European Explorations in North America, 1565-1690

Map: Explorations of Terra Australis

Map: Edmond Haley's

“Magnetic Declination Map” (1701)

II. Knowledge of the World:

The New Cartography

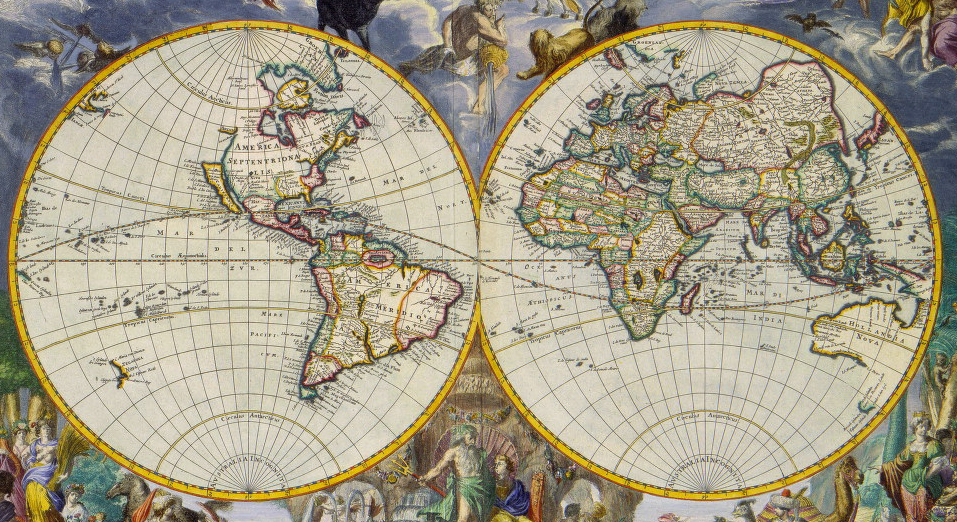

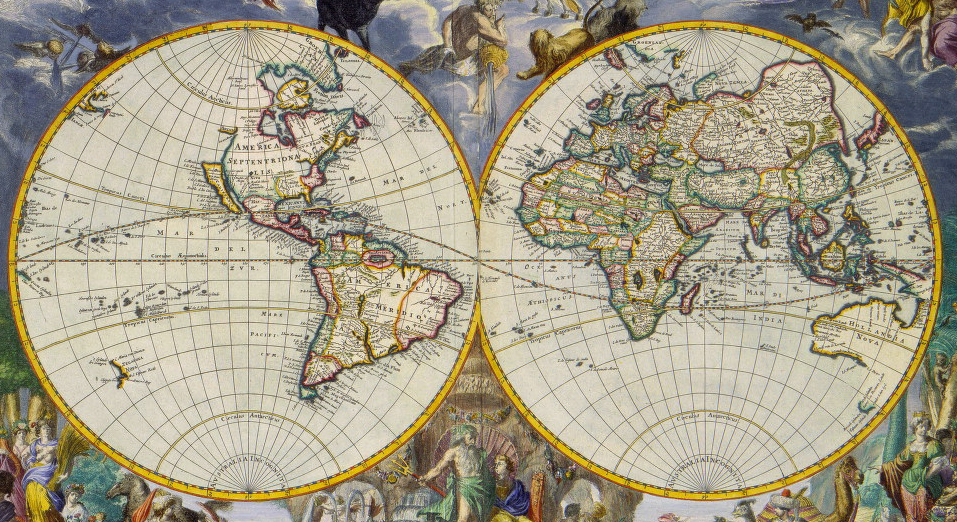

Image: Gerhardus Mercator, Orbis

Terrae Compendiosa Descriptio (1595)

Image: The Hereford Map (13th century)

Image: A Portolan Chart of the Mediterranean,

1489

Image: A Japanese Portolan Map, 17th C.

Image: Mercator's Projection,

1569

III. Europeans Abroad

A. Warfare with Non-Europeans

B. European Competition, Local Cooperation, and the Projection of

Power

Map: The Mystic Massacre, May 26, 1637

IV. Colonization, Slavery, and

Consumption

A. From Tribute Extraction to Capitalism

B. A Case in Point: Slave Economies and the Middle Passage

C. Slavery and Sugar: Creating a Consumer Society

Animation: The Atlantic Slave Trade

Map: The Atlantic Slave Trade

Chart: Annual Sugar Consumption in England, 1731-1780

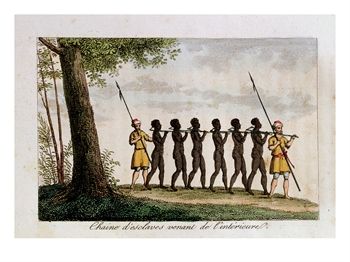

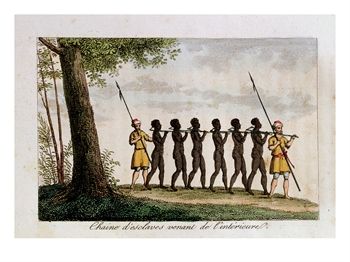

Image: Chaine d'esclaves venant de l'interieur,

from René Claude Geoffroy de Villeneuve, L'Afrique, ou histoire,

moeurs, usages et coutumes des africains: le Sénégal (Paris,

1814), vol. 4, facing p. 43. The author lived in the Senegal region

for about two years in the mid-to-late 1780s and made this drawing from

his own observations. He provides a detailed description of the capture

and the movement of slaves from the interior to the coast: “Every

year the Mandingo traders, called slatées or Sarakole [Sarakule,

Sarracolet, etc.] Negroes, after having sold slaves in exchange for

European goods, leave with necessary goods for the interior, toward

Bambara country. The Mandingo slatées often carry with them iron

bolts of 15 to 18 inches long...They cut pieces of a heavy wood, around

5 or 6 feet long, forked at one end so that the forked end can fit around

the slave's neck. The two ends of the forked branch are drilled/pierced

so as to permit the iron bolt, held at one end by a head, and fixed

to the other end by a flexible iron blade [which passes] through a hole

in the bolt...When all the slaves are run through in this fashion and

the traders want to start the march to the coast, they arrange the captives

in a single file. One of the traders puts himself at the head of the

line, loading on his shoulder the handle of the forked branch of the

first black; each slave carries on his shoulder the handle of the forked

branch of the person behind him...During the entire route, the fork

is never removed from the slaves' necks, and at the arrival point, as

at the departure, the traders take great care to check if the iron bolts

are in good working condition. It is thus that five or six armed traders,

without fear, can succeed in conveying coffles of 50 slaves, and even

more, from the interior to the European coastal factory.” Commentary: The

Atlantic Slave and Slave Life in the Americas, University of Virginia.

Image source: Allposters.com.

|

.jpg)

Image: Fortress of Melaka (1630)

Image: Zheng Chenggong

(1624-1662)

Map: "The Island of Formosa" (1726)

Map: The Mughal Empire

Map: The Safavid Empire

Map: European Settlements in India (1498-1739)

Image: Batavia (1681)

Image: Plan de Pondicherry (1741)

Map: Map of India in 1767

Map: The Banda Islands (Indonesia)

Image: Fort Nassau (1646) |

.jpg)