Judicial Torture in Eighteenth-Century Europe

Judicial Torture in Eighteenth-Century Europe

If one were to judge solely by the arguments that Voltaire presented in his “Essay on Toleration” (1763), one might conclude that the Enlightenment knocked the foundation out from under the regime of judicial torture. Among other things, Voltaire objected to the “legally sufficient indications” of guilt that were allowed judges to proceed with judicial torture to extract a confession. Not long after Voltaire’s death (1778), in royal declarations of 1780 and 1788, King Louis XVI formally abolished all forms of judicial torture in France.

But this comforting story is nothing more than a fairy tale, and for three main reasons:

1) It ignores the fact that judicial torture, like capital executions, was already declining long before the eighteenth century. In Munich, for example, the use of judicial torture dropped from about 44% of criminal inquests in 1650 to only 16% in 1690.

2) It operates on the assumption that the moral outrage of intellectuals is enough to move mountains. The problems with this are obvious: eighteenth-century critics were advancing arguments that, in various forms, had been circulating for centuries; already in the late seventeenth century, for example, numerous intellectuals had argued against its use in cases of witchcraft and magic. And since the sixteenth century critics of judicial torture had argued that torture measured not the truth but an individual’s ability to withstand pain every.

3) It also assumes that judicial torture and the goals of Enlightenment were necessarily opposed to one another. For the followers of Voltaire, to be sure, they were inextricably tied. But others sought to “tame” the regime of judicial torture by standardizing and regulating the conditions under which torture could be used.

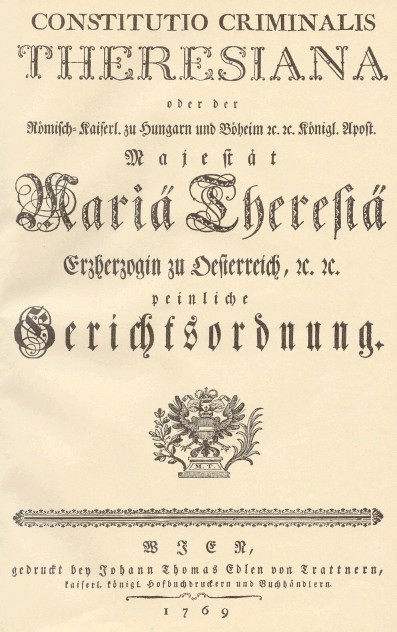

One of these was the Constitutio Criminalis Theresiana—the Criminal Code of Maria Theresia, Archduchess of Austria, promulgated in 1768, five years after the publication of Voltaire's famous essay. The Theresiana was meant to introduce uniform criminal law and procedure throughout the Habsburg Crown Lands and remained in effect until the reforms of Emperor Joseph II in 1787. To that end, it included a series of appendices, which showed how judicial torture should properly be applied. (The law did not apply in Hungary).

Image: the rack (Streckleiter)

Image: strappado (Hochziehen)

Image: thumbscrews

(Daumenstock)