The Republic aimed to rebuild society and culture from the bottom up, to transform it so utterly that a transparent and virtuous republic could take root in France. This meant creating new values and a system of symbols, rituals, and observances to make them stick. The Republic tried to do this all at once, advancing simultaneously and vigorously on all fronts. The predicatble effect was to politicize life to a degree that had not been seen since the Wars of Religion, two hundred years before. As Censer and Hunt observe, even the smallest gestures could become signs of revolutionary fervor or counterrevolutionary defiance.

To be sure, not all opposition, to be sure, was stimulated by the Republic’s intrusions: protests against high grain prices, for example, continued right along as if the Revolution had never happened.Nor was all opposition counterrevolutionary, strictly speaking: in the provinces, it proved possible to rally constitutional monarchists (who had welcomed the Revolution) with the defenders of local autonomy (who included many opponents of the Revolution) in common cause against the centralizing Committee for Public Safety. This kind of opposition was seated in cities, especially, which were jealous of the freedoms that they had gained during the first phase of the Revolution.

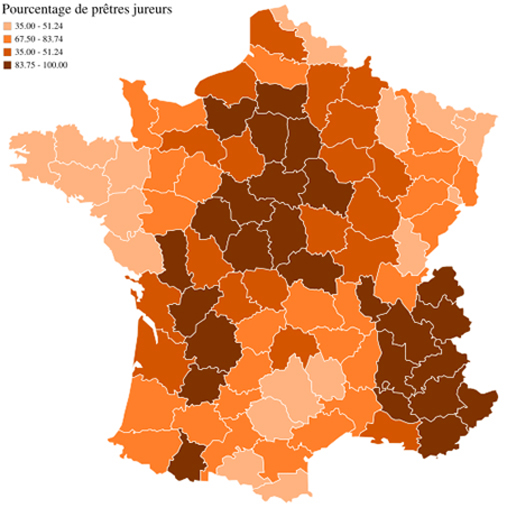

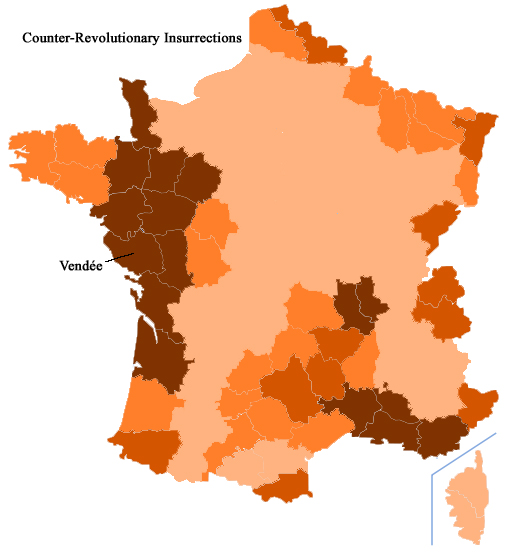

In rural France, though, the opposition was increasingly counterrevolutionary, and its inspiration was often religious in nature. This comes across most clearly when we compare the two maps at left. The first shows rates of execution under the Terror--a crude but useful indicator of the geographic distribution of militant opposition to the Republic. The lower chart indicates the percentage of priests who took the oath of loyalty to the Republic: the darker the shading, the higher the percentage of oath-taking priests in a particular département.

The two maps are mirror opposites of one another, which suggests how important was the role of priests in stirring up opposition to the Revolution. For priests, it was a matter of life and death: de-Christianization was aimed right at them. But for the rural population at large, too, the Revolution had become more a curse than a blessing: rural folk had benefited enormously from the dismantling of the seigneurial system in 1789, but since then the Revolution had worked as much against the interests of peasants as in their favor; now, in 1793, the Convention was attempting to abolish Christianity itself.

Resistance was most intense in western France—always a center of opposition to central authority—especially in the Département of the “Vendée,” situated to the south of the Loire river from the city of Nantes. There, between the spring of 1793 and the spring of 1794, a “Catholic and Royal Army” composed of artisans, peasants, and weavers carried out an armed insurrection against the National Guard, assassinating Jacobins and even occupying several towns in the region. The Vendée rebellion was crushed even more brutally than the revolt of the cities—tens of thousands of peasants were slaughtered; something like one third of the population of the Vendée did not survive the uprising. By the summer of 1794, counterrevolution had been defeated decisively; but a guerilla war continued throughout 1795 and revived again in 1799.