National

Socialist Welfare

National

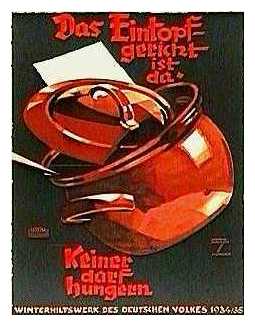

Socialist Welfare In addition to make-work programs, the National Socialist regime also introduced welfare programs that were designed to link poverty relief with sacrifice for the common good of the racial community, or Volksgemeinschaft. The principal manifestations of this endeavor were the Winter Relief Agency (Winterhilfswerk or WHW) and the National Socialist People's Welfare (NS-Volkswohlfahrt or NSV).

The WHW was founded in September 1933 under the supervision of the Propaganda Ministry to coordinated the collection of money and supplies for emergency relief to needy or homeless “racial comrades.” WHW volunteers, often members of the Party, the HJ, and BDM collected donations door-to-door or on the street; people who donated received a token lapel-pin, which soon one of the most visible signs of National Socialist rule in everyday life. Something like 8,000 different tokens, each corresponding to a distinct fund-raising campaign, were produced between October 1933 and March 1943.

Image: “BDM im Dienste des Winter-Hilfswerk des deutschen Volkes 1934/35,” 120 x 80 cm; Source: Deutsches Historisches Museum (1990/532). The slogans read “Everyone will be wearing the Winter-Hilfswerk flower on Sunday, November 4” (Jeder trägt am Sonntag 4. November die Blume des WHW) and “You too must give!” (auch Du mußt opfern!).

This

token is from a collection undertaken in January 1934 and bears the slogan

“Protect the Family -- We Sacrifice”. The object, greatly enlarged here,

has a diameter of 2.5 centimeters. To see more examples of the these tokens,

click

This

token is from a collection undertaken in January 1934 and bears the slogan

“Protect the Family -- We Sacrifice”. The object, greatly enlarged here,

has a diameter of 2.5 centimeters. To see more examples of the these tokens,

click  Despite

widespread corruption, the WHW managed provide relief to large numbers of

people--about 10,000,000 received parcels or cash in the winter of 1937,

for example. In Berlin alone, some 75,000 WHW volunteers collected 375,000

RM in October 1935.

Despite

widespread corruption, the WHW managed provide relief to large numbers of

people--about 10,000,000 received parcels or cash in the winter of 1937,

for example. In Berlin alone, some 75,000 WHW volunteers collected 375,000

RM in October 1935.