How was Hitler able to establish dictatorial power in the first place? Hitler had been appointed Chancellor of Germany on 30 January 1933 at the head of a cabinet consisting mostly of nationalist conservatives who believed that they could harness his movement to their purposes. When Hitler became chancellor, there was no certainty that he would achieve dictatorial rule. How did he do it? One argument is that Hitler was able to impose a dictatorship in part because there was never a single, revolutionizing moment in his “seizure” of dictatorial power that might have mobilized the opposition.

- For one thing, Hitler’s appointment as chancellor had been legal—no one could deny that.

- This was hobbling for the pro-Republican forces on the center and the left (Z, DDP, SPD), which were concerned to preserve the Weimar Republic: how could they rise up in defense of the Republic against a legitimately appointed Chancellor?

- In addition, Hitler appeared initially to be hemmed in by his cabinet: only three were Nazis, and of these one (Göring) had no “portfolio,” i.e., he enjoyed membership in the Cabinet without heading any governmental ministry at the Reich level.

- Finally, Hitler proceeded to establish his dictatorial rule by means that gave the appearance, at least, of legality.

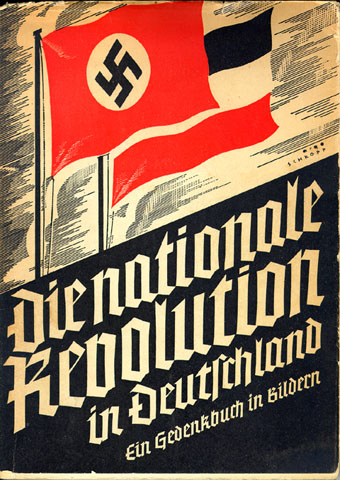

Image right: the cover of a pamphlet commemorating Hitler's appointment as chancellor, what National Socialists called the "Seizure of Power" (Machtergreifung) or "National Revolution" (die nationale Revolution). Source: Wilhelm Köhler, Die nationale Revolution in Deutschland. Ein Gedenkbuch in Bildern (Minden: Druck und Verlag von Wilhelm Köhler, 1933); Source: German Propaganda Archive at Calvin College.

1)

The

Intensification of Executive Powers:

Above and beyond the consolidation

of police powers in Prussia, Hitler set in motion a massive intensification

of executive power on the legal basis of presidential decree. His first

move in this direction came the day after his appointment, when Hitler

persuaded the president to dissolve the Reichstag and call new elections for March 5. In those elections—which were not quite free elections—the

NSDAP garnered 43.9%; with the added votes of the DNVP (8%), Hitler

could command just over half the Reichstag.

- But the crucial event in the

intensification of executive power occurred on 27 February 1933,

when the Reichstag building went up in flames:

- Ever since that day, historians have debated ever since whether the fire was set by the Nazis, or if it was set by a single arsonist acting alone (a Dutch Communist, Marinus van der Lubbe) as the government alleged.

- Marinus van der Lubbe was charged with the crime, tried, and found guilty; the best evidence suggests that the Nazis weren’t lying about this one, that in fact van der Lubbe did set the fire.

Either way, it was an incredible stroke of good luck, which Hitler exploited to the fullest:

- On 28 February 1933, Hitler issued the “Reichstag Fire Decree”: this suspended all constitutional protection of political, personal, and property rights; it also declared a state of emergency—that being the threat of a Communist revolution.

Once again, Hitler had chosen well: by arranging to have himself appointed as a “presidential chancellor,” he was able to appropriate the President’s emergency powers to suspend the very constitution they were designed to protect.

- Within 48 hours after the fire, some 10,000 political opponents rounded up and crammed into makeshift SA prisons, concentration camps, and torture chambers; virtually all of them were Communists and Social Democrats.

- These emergency decrees also enabled the new regime to ban political speech: thus on 21 March 1933, the “Rumor Decree” forbade criticism of the regime or the NSDAP, even if the statement were true.

2)

Coordination

of the State Governments:

The “Reichstag Fire Decrees”

amounted to a fundamental law of the Nazi regime; they also enabled Hitler

to suspend all existing state governments and replace them with commissars—like

Göring in Prussia—appointed from the national capital in Berlin. The

final clause of the Reichstag Fire Decree stipulated that

If a state fails to take the necessary steps for the restoration of public safety and order, then the Central Government is empowered to take over the relevant power of the highest state authority.

Hitler used this as a blanket excuse to subordinate state governments and overthrow the non-compliant ones. Many of the smaller states—where the NSDAP already participated in governing coalitions—had already been subordinated to central authority in February.

- During the first two weeks of March—exploiting the momentum gained by the election results on 5 March—the central government used its emergency powers to place all the remaining state governments under the auspices of a centrally-appointed “Reich Commissioner.” This would give the regime indirect control over police forces outside of Prussia (which was already under its control).

- In state after state, governments

surrendered to a combination of SA intimidation, ultimatums, and blackmail;

in several instances, the change of guard resembled a coup d’état:

§ In Württemberg, an overthrow was led by a centrally-appointed state police commissioner (Jagow)

§ The last holdout against these takeovers was Bavaria—ironically, where the Nazi party was born—on 10 March 1933; there, Minister President Heinrich Held (BVP) succumbed to by a veritable overthrow (Epp).

3) The

“Legal” Transfer of Legislative Power:

The final deed in the transition

to dictatorship was an act of parliament: the so-called “Enabling Act”

of 23 March 1933, which formally transferred legislative authority

to the Hitler Cabinet.

- Though the NSDAP-DNVP government enjoyed a parliamentary majority, a supermajority of two-thirds would be required to transfer any constitutional powers to the executive.

- Despite the Nazi gains on March 5, the SPD and the Z still possessed a large enough bloc of votes to prevent a two-thirds majority.

- But on 23 March, the Center

Party delivered the final, fatal blow to parliamentary democracy in Germany

by agreeing to support the legislation despite the lack of a quorum in

the Reichstag—which had resulted from the illegal exclusion of KPD delegates.

- To make a long and complex story short, the Center Party agreed to a Hitler dictatorship in return for guarantees that the new regime would respect the rights of the Catholic church.

- Thus the Enabling Act passed, by a vote of 444 in favor to 94 opposed—every one cast by a Social Democrat.

4) “Revolution

from Below”:

It is crucial to remember

that behind the façade of legality lay the threat of brutal political

violence. The pressure on non-Nazis to comply was relentless: on the day

of the vote on the Enabling Act, a crowd formed outside the building where

the Reichstag sat ; a Bavarian Social Democrat recalled the scene he encountered

on entering the building:

We were received with wild choruses: ‘We want the Enabling Act!’ Youths with swastikas on their chests eyed us insolently, blocked our way, in fact made us run the gauntlet, calling us names like ‘Center-Party pig,’ ‘Marxist sow.’ The [Reichstag] building was crawling with armed SA and SS men…The assembly hall was festooned with swastikas and similar ornaments….When we Social Democrats had taken our seats on the extreme left, SA and SS men lined up at the exits along the walls behind us in a semicircle. Their expressions boded no good.

Throughout February and March, too, the opposition was treated to a wave of SA violence and intimidation: the so-called “Revolution from Below”:

- KPD demonstrations against Hitler on 31 January were broken up by SA and SS attacks—most famously at Breslau.

- Throughout Germany, SA men attacked the headquarters of labor unions and of the Communist and Social Democratic parties

- Historian Richard Bessel argues that the effect of all this was devastating: the “within roughly two months of Hitler’s appointment as Reich Chancellor,” he writes, “open opposition to the Nazis had disappeared.”

In all this, the Nazis were quite explicit about their intentions. Here is how the district party boss Wilhelm Murr phrased them at a victory rally after the takeover in Württemberg (15 March):

The government will brutally beat down all who oppose it. We do not say, ‘an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth.’ No, he who knows out one of our eyes will get his head chopped off, and he who knocks out one of our teeth will get his jaw bashed in.

In view of such intimidation, the political parties of Weimer were destroyed or dissolved themselves:

- The Social Democratic Party (SPD): Banned June 22

- The German People's Party (DVP): Dissolves itself June 28

- The German National People's Party (DNVP): Dissolves itself June 27

- The German Democratic Party (DDP): Dissolves itself July 4

- The Bavarian People's Party (BVP): Dissolves itself July 4

- The Center Party: Dissolves itself July 5

- 14 July 1933: the Party Law bans all parties except NSDAP—a legal confirmation of realities already in place since early July.

Return to 443/543 Homepage

A Revolution

by Installments

A Revolution

by Installments