|

Who Became a National Socialist? Who Voted for Hitler?

To find out what sort of person voted for the NSDAP or who joined the

party is not as easy a task as it might seem. Problems begin with the distinction

between voter and party member: the two groups overlapped, of course, but

they were not identical. The two groups present very different methodological

problems as well. The social characteristics of party members, for example,

can be established with far greater specificity than is possible with voting

constituencies. For information about party members, one can use the NSDAP's

own membership, which are housed in the Berlin Document Center. But balloting

in pre-1933 Germany was secret, so for information on Nazi party voters

one

must deduce their social and cultural characteristics from comparisons

between election results and the make-up of localities that produced them. |

|

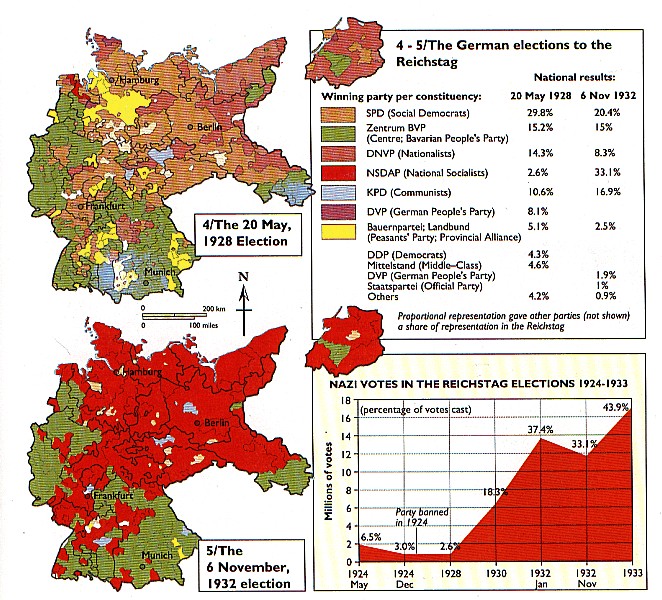

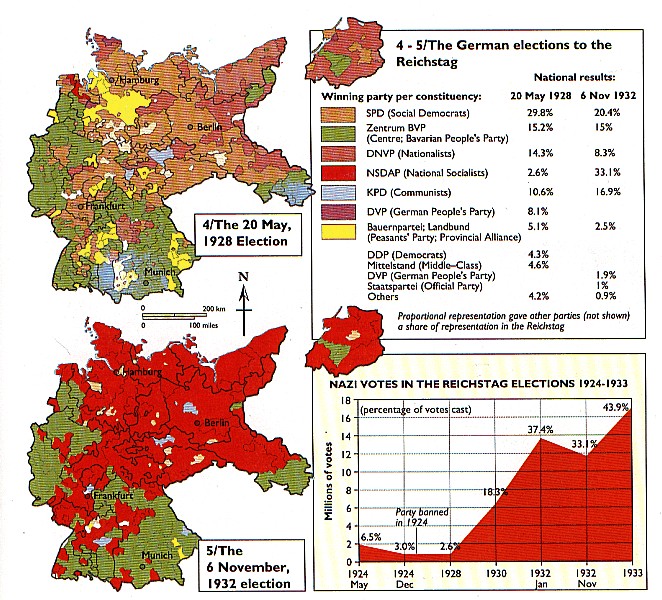

Starting with the big picture, several obvious patterns emerge. One

is a relationship between region, religion, and National Socialism. The

map at the right compares Reichstag election returns from 20 May

1928 and 6 November 1932, broken down by administrative district. A comparison

between the results of these two elections reveals that certain regions

in the west and south were highly resistant to Nazi inroads; these regions

were predominantly Roman Catholic by religion, strongholds of the Center

Party (or Zentrum). In the Reichstag elections of July 1932,

42% of German Catholics voted Zentrum or the Bavarian People's Party

(its sister-party in Bavaria). This points at one of the strongest correlations

in Nazi voting behavior: the NSDAP typically fared best in Protestant regions

of Germany, poorest in the Catholic parts.

Many historians argue that a similar correlation

existed between class and voting: the NSDAP performed less well in heavily

industrialized districts with large working-class populations, and this

seems to be born out by the resilience of the Social Democratic and Communist

constituencies during the period between 1928 and 1933, when the NSDAP

became the largest single party in Germany. Thus 40-45% of blue collar

workers voted for the SPD or the KPD in 1932, while only 10% of workers

voted for one of the Catholic parties. The remainder were divided among

the various bourgeois parties of the middle and right; by 1930 most of

these were voting for the NSDAP. But overall, Nazis remained a minority

among blue-collar voters. (Map source: Richard Overy, The Penguin Historical

Atlas of the Third Reich (1996), 21). |

All this suggests that the biggest shifts in voter behavior took place

within the middle classes—as the collapse of the bourgeois parties suggests

(see Reichstag Election Results, 1919-1932).

The idea in a nutshell, is that the Nazi party owed its success to a middle-class

defection from the Republic, its values and institutions. By why? Historians

have devised several theories to explain this shift.

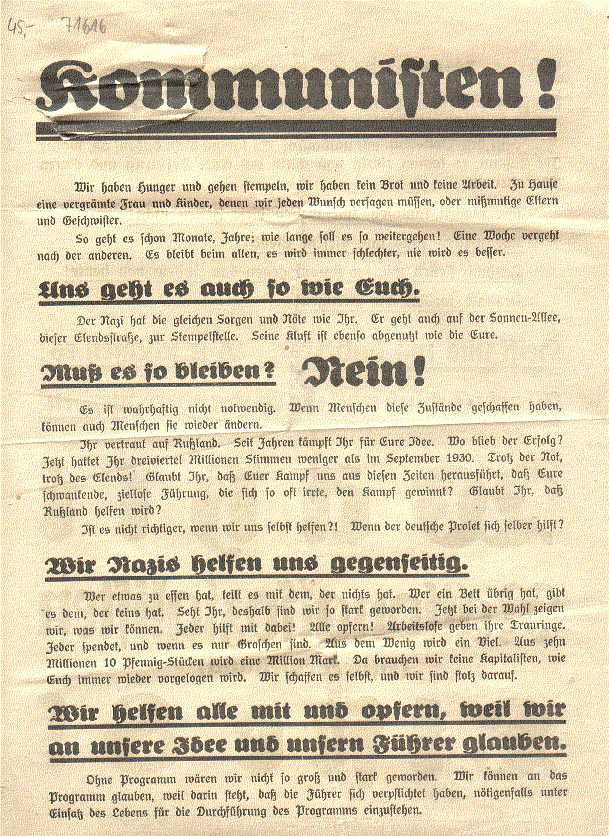

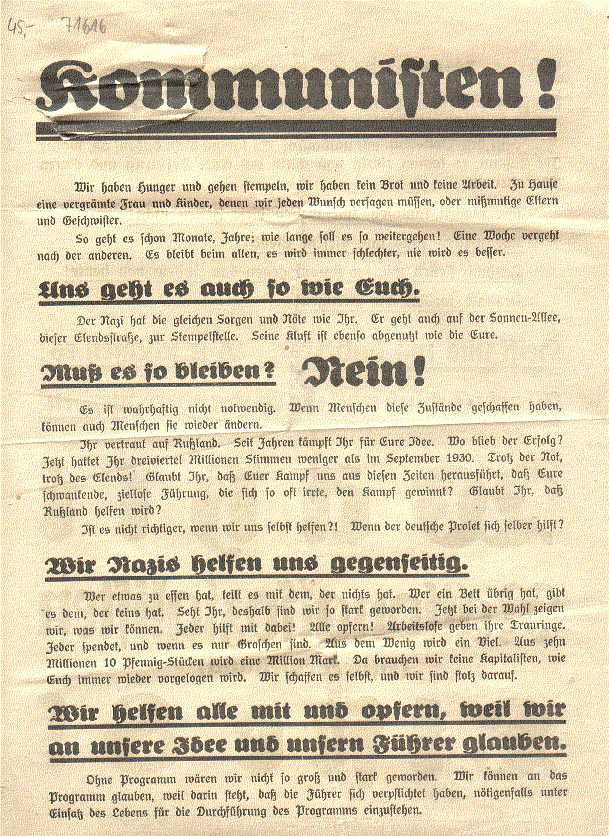

This Nazi campaign flyer, from 1932, is directed at Communists

and offers them mutual aid and support if they abandon their party and

vote National Socialist. Source: German

Propaganda Archive. |

1) Mass Psychology:

This is the idea that Nazism's appeal was deeply psychological, rooted

in irrational fears of isolation in an atomized, industrial society. Nazism

seemed to offer a sense of purpose and community to people who lacked both.

For many Germans, according to this view, Nazism offered the promise of integration in a purposeful community,

a way out of the rootlessness of modern life. According to this hypothesis, one would expect Nazism to resonate most strongly among the least integrated

social groups, such as war veterans, unmarried youth, and victims of the

Great Depression—in other words, people among whom feelings of isolation and powerlessness were

most pronounced. By the same token, one would also expect to find that Nazism appealed least

in highly integrated communities. |

2) Middle-Class Panic:

In his classic study, The Nazi Seizure of Power,

William Sheridan Allen argued that after the Great Depression struck, middle

class Germans turned to Nazism not because they had suffered greatly but

because they feared that they might. Such concerns were especially

pronounced among the lower middle class, especially members of the “old”

middle class occupations—independent artisans and retailers, middling farmers,

employees. These were the people who were most vulnerable to the effects

of an industrialized, consumer-oriented economy, who were the most exposed

to the threat of a decline in social status, who were in the greatest danger

of descending socially into the “proletariate.” In contrast to the established middle

class parties, the NSDAP exhibited vitality and dynamism; to members of

the “old” middle class, Nazism promised a restoration of their social,

economic, and political importance. |

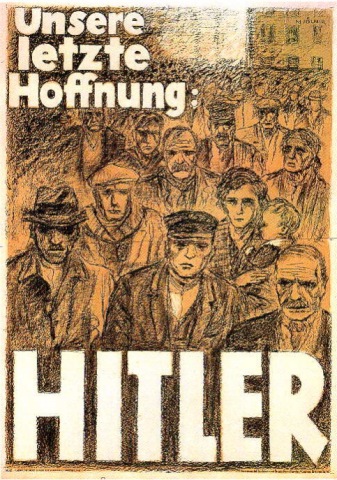

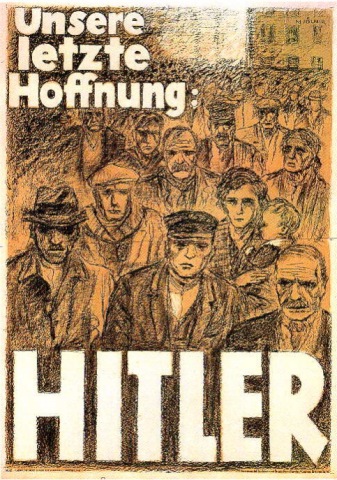

This poster from the November 1932 elections declares

Hitler to be “our last hope”. Source: German

Propaganda Archive. |

This Reichstag campaign poster from 1932 promises

to deliver a “final blow” to the Center Party—symbolized by a Catholic

priest—and the Marxist parties of the left. Source: German

Propaganda Archive. |

3) Political 'Confessionalism':

Why did some social groups prove so vulnerable to Nazism, while others

did not? The theory of political confessionalism draws on the 'mass psychology'

thesis to explain why certain middle-class groups were resistant to Nazism,

while others became easily frustrated with the political parties that represented

them. From the 'mass psychology' theory it borrows the idea that poorly

integrated people were especially susceptible to the NSDAP's appeals; it

adds the notion that political parties that offered strong identities and

dense social networks that 'immunized' their members against Hitler. These effects

were most pronounced among German Catholics—hence resilience of electoral districts in which the party of political Catholicism, the Zentrum, did well at the polls—and among members of the Social Democratic Party (SPD) and the

Communist Party (KPD). All of these parties provided their members far more than

ideology; they offered a rich associational life, a sense of common purpose

and distinction. |

How does the evidence stack up? To find out, go to:

1) Mass Psychology

Age of new NSDAP members, 1925-1933

Unmarried new NSDAP members,

1925-1933

Residence of new NSDAP members,

1925-1933

2) Middle-Class Panic

New NSDAP members, yearly

by class, 1920-1944

New NSDAP members, by occupational

group, 1925-1933

New NSDAP members, male and female,

by occupational group, 1925-1933

New NSDAP members, by class,

1925-1933

3) Political 'Confessionalism'

New NSDAP by confessional

context, 1925-1933

Social composition of the NSDAP,

1942

A Final Note: Women

and National Socialism

Voting Behavior According

to the Sex of the Voter

Percentage of

Women's and Men's Vote for the Hitler/NSDAP

Bibliography:

William Sheridan Allen, The Nazi Seizure

of Power: The Experience of a Single German Town, 1922-1945, 2d ed.

(New York: Watts, 1984).

Thomas Childers, The Nazi Voter: The

Social Foundations of Fascism in Germany, 1919-1933 (Chapel Hill: University

of North Carolina Press, 1983)

——, “Who, Indeed, Did Vote for Hitler?,”

Central

European History 17 (1984): 45-53.

——, ed., The Formation of the Nazi Constituency,

1919-1933 (Totowa: Barnes & Noble, 1986).

Jürgen W. Falter, Hitlers Wähler

(Munich: Beck, 1991).

——, “Wer wurde Nationalsozialist?: Eine Überprüfung

von Theorien über die Massenbasis des Nationalsozialismus anhand neuer

Datensätze zur NSDAP-Mitgliedschaft 1925-1933,” in Helge Grabitz et

al., Die Normalität des Verbrechens: Bilanz und Perspektiven der

Forschung zu den nationalsozialistischen Gewaltverbrechen (Berlin:

Edition Hentrich, 1994), 20-41.

——, “The Social Bases of Political Cleavages

in the Weimar Republic, 1919-1933,” in Larry Jones and James Retallack,

eds., Elections, Mass Politics, and Social Change in Modern Germany:

New Perspectives (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992).

Johnpeter Horst Grill, THe Nazi Movement

in Baden, 1920-1945 (Chapell Hill: University of North Carolina Press,

1983).

Richard F. Hamilton, Who Voted For Hitler?

(Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1982).

——, “Braunschweig 1932: Further Evidence

on the Support for National Socialism,” Central European History

17 (1984): 3-36.

Oded Heilbronner, Catholicism, Political

Culture, and the Countryside: A Social History of the Nazi Party in South

Germany (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1998).

Michael Kater, The Nazi Party: A Social

Profile of Members and Leaders, 1919-1945 (Cambridge: Harvard University

Press, 1983).

Detlef Mühlberger, Hitler's Followers:

Studies in the Sociology of the Nazi Movement (London: Routledge, 1991).

Helena Waddy-Lepovitz, “Beyond Statistics

to Microhistory: The Role of Migration and Kinship in the Making of the

Nazi Constituency,” German History 19 (2001): 340-368.

Return to

443/543 Homepage