1) After the consolidation of dictatorial power but before the radicalization

of the late 1930s, three tendencies gave structure to Hitler's regime and

his position in it:

-

Perhaps the primary characteristic of this period was the increasing fragmentation

of power: the splintering of government and the Party into separate

and self-interested agencies with competing and overlapping jurisdictions,

each of them dependent to Hitler's individual will as Führer.

-

During these years as well, Hitler's racial and expansionist goals—present

in various forms from his earliest days of political activity—acquire sharper

focus than before.

-

At the same time, Hitler became both increasingly withdrawn from domestic

politics and intolerant of differing opinions, even coming from his

closest associates.

Finally, these were the years when Hitler's personal prestige expanded

to the point where his will could not be challenged—to a point, in other

words, where Hitler's will was absolute. |

Image: from an unofficial pamphlet commemorating Hitler's

appointment as chancellor. In the rear stands the new Interior Minister,

Wilhelm Frick. The caption reads, "Hitler greets the President on Memorial

Day" (12 March 1933). Source: Wilhelm Köhler, Die nationale Revolution

in Deutschland: Ein Gedenkbuch in Bildern (Minden: Köhler,

1933); German Propaganda

Archive at Calvin College. |

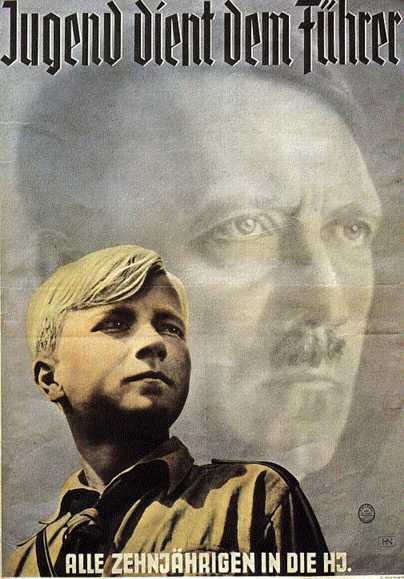

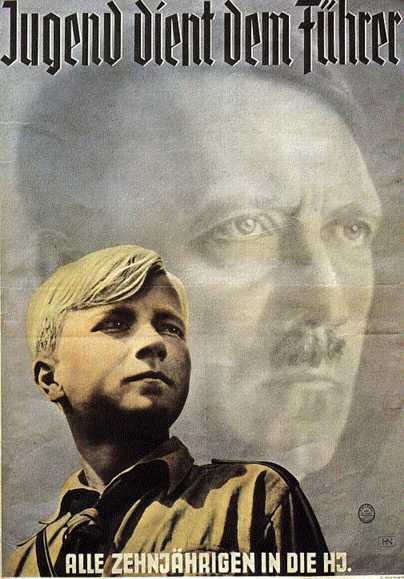

Image: "Youth Serves the Führer." Source: German

Propaganda Archive at Calvin College. |

2) These tendencies were interrelated. As Kershaw writes:

"Hitler's personal actions...were vital to the development.

But the decisive component was that unwittingly singled out in his speech

by Werner Willikens. Hitler's personalized form of rule invited radical

initiatives from below and offered such initiatives backing, so long as

they were in line with his broadly defined goals. This promoted ferocious

competition at all levels of the regime, among competing agencies, and

among individuals within those agencies. In the Darwinian jungle of the

Third Reich, the way to power and advancement was through anticipating

the 'Führer Will,' and, without waiting for directives, taking initiatives

to promote what were presumed to be Hitler's aims and wishes."

|

3) Hitler was, therefore, at one and the same time the absolutely indispensable

fulcrum of the entire regime, and yet largely detached from any formal

machinery of government. This enables us to explain Hitler's paradoxical

ability to remain aloof from much practical decision-making and to

increase his personal power in the process:

-

Through the dynamics of “working toward the Führer”, initiatives

were taken and policies adopted in ways that fell in line with Hitler's

aims, but without the dictator necessarily having to dictate.

|

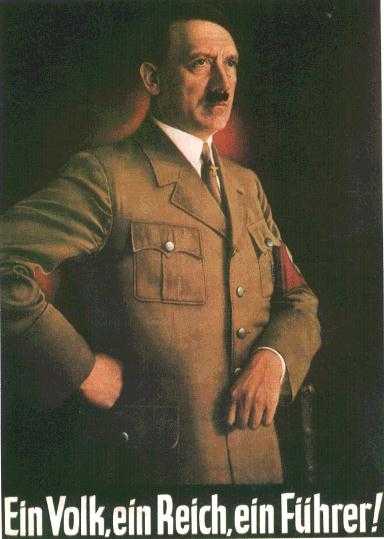

Image: from a pamphlet of photographs taken by Heinrich Hoffmann

entitled The Hitler No One Knows [Hitler wie ihn keiner kennt]

(Berlin: Zeitgeschichte Verlag, 1932). Source: German

Propaganda Archive at Calvin College. |

Hitler reviews a parade at the 1938 Party Rally at Nürnberg--the

last of its kind before the outbreak of war terminated the annual event.

Source: Hanns Kerrl, Reichstagung in Nürnberg 1938 (Berlin:

C. M. Weller, 1939), German

Propaganda Archive at Calvin College. |

4) The result, perhaps inevitably, was a high level of governmental

and administrative disorder. More ominously, competition encouraged the

continuous,

cumulative radicalization of policy in the direction of making

realities out of Hitler's own ideological obsessions. This process also

swelled Hitler's already immense ego, magnifying his already strong megalomaniac

tendencies, deepening his contempt for caution, even as his successes in

foreign and domestic policy made effective resistance to his regime less

and less viable. |

“Working

Toward the Führer”

“Working

Toward the Führer”