The “Stahlecker Report” (15 October 1941) [excerpts]

The following is an excerpt from the first of two summary reports compiled

by SS-Brigadeführer Franz Walter Stahlecker, commander of Einsatzgruppe A,

and sent to Security Service Headquarters in Berlin. Einsatzgruppe A was deployed behind the German front line as it advanced through the

Baltic countries. With enclosures, the entire document is over 130 pages

long, far and away the most extensive of all the Einsatzgruppen operational

reports. It and the “Jäger Report” are also distinguished by the fact

that they were written by commanding field officers and were not altered

in the editorial process that affected most of the other operational reports.

The document records a shift from encouraging local populations to engage

in “autonomous cleansing actions” (pogroms) during the first weeks after

the invasion to one of systematic genocidal killing. Significantly, the

report refers to “orders” received concerning “cleansing operations aimed

at a maximum elimination of the Jews.” Estonian partisans killed Stahlecker

on 23 March 1942; see Ronald Headland, Messages of Murder: A Study of

the Reports of the Einsatzgruppen of the Security Police and the Security

Service, 1941-1943 (London and Toronto, 1992), 152-154].

Headings:

“Encouragement of Autonomous Cleansing Actions (Selbstreinigungsaktionen)”

“The Fight against Jewry”

Bibliography

|

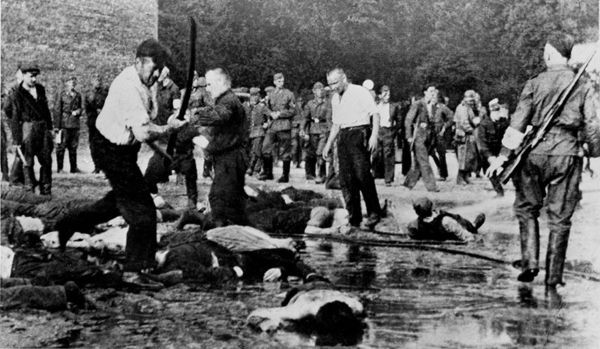

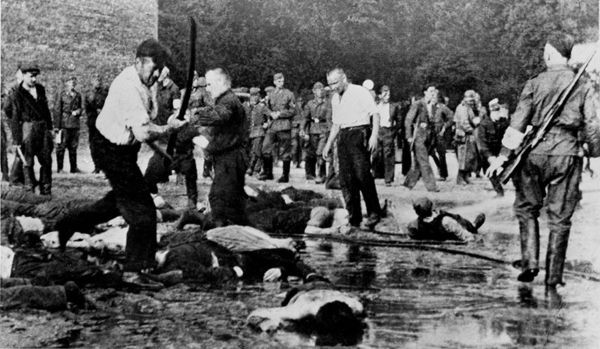

Image: In his report of 15 October 1941, SS-Brigadeführer Stahlecker describes the efforts of Einsatzgruppe A to foment so-called “Autonomous Cleansing Actions” (Selbstreinigungsaktionen) among Lithuanians against the Jewish population. This photograph documents such an “autonomous” pogrom, carried out in Kaunas/Kovno on 25-29 June 1941. “Both in Kovno and in Riga,” the report notes, “evidence was taken on film and by photographs to establish, as far as possible, that the first spontaneous executions of Jews and Communists were carried out by Lithuanians and Latvians.” This photograph, and the series to which it belongs, is one of these documentations. Source: Topographie des Terrors. |

Secret Reich Business!

40 Copies

23rd Copy

Einsatzgruppe A

General Report up to October 15, 1941

[…]

II. Cleansing and Securing the Area of Operation

1) Encouragement of Autonomous Cleansing Actions (Selbstreinigungsaktionen).

Basing [ourselves] on the consideration that the population of the Baltic

countries had suffered most severely under the rule of Bolshevism and Jewry

while they were incorporated into the USSR, it was to be expected that

after liberation from this foreign rule they would themselves to a large

extent eliminate those of the enemy left behind after the retreat of the

Red Army. It was the task of the Security Police to set these self-cleansing

movements going and to direct them into the right channels in order to

achieve the aim of this cleansing as rapidly as possible. It was no less

important to establish as unshakable and provable facts for the future

that it was the liberated population itself which took the most severe

measures, on its own initiative, against the Bolshevik and Jewish enemy,

without any German instruction being evident.

In Lithuania this was achieved for the first time by activating the

partisans in Kovno. To our surprise, it was not easy at first to

set any large-scale anti- Jewish pogrom in motion there. Klimaitis, the

leader of the partisan group referred to above, who was the first to be

recruited for this purpose, succeeded in starting a pogrom with the aid

of instructions given him by a small advance detachment operating in Kovno

[Kaunas/Kauen], in such a way that no German orders or instructions could

be observed by outsiders. In the course of the first pogrom during the

night of June 25/26, the Lithuanian partisans eliminated more than 1,500

Jews, set fire to several synagogues or destroyed them by other means,

and burned down an area consisting of about sixty houses inhabited by Jews.

During the nights that followed, 2,300 Jews were eliminated in the same

way. In other parts of Lithuania similar Actions followed the example set

in Kovno, but on a smaller scale, and including some Communists who had

been left behind.

These autonomous cleansing actions ran smoothly because the Wehrmacht

authorities who had been informed showed understanding for this procedure.

At the same time it was obvious from the beginning that only the first

days after the occupation would offer the opportunity for carrying out

pogroms. After the disarmament of the partisans the self-cleansing Actions

necessarily ceased.

It proved to be considerably more difficult to set in motion similar

cleansing actions and pogroms in Latvia. The main reason was that the entire

national leadership, especially in Riga, had been killed or deported by

the Soviets. Even in Riga it proved possible by means of appropriate suggestions

to the Latvian auxiliary police to get an anti-Jewish pogrom going, in

the course of which all the synagogues were destroyed and about 400 Jews

killed. As the population on the whole quieted down very quickly in Riga,

it was not possible to arrange further pogroms.

Both in Kovno and in Riga evidence was taken on film and by photographs

to establish, as far as possible, that the first spontaneous executions

of Jews and Communists were carried out by Lithuanians and Latvians.

In Estonia there was no opportunity of instigating pogroms owing to

the relatively small number of Jews. The Estonian self-defense units eliminated

only some individual Communists, who were particularly hated, but in general

limited themselves to carrying out arrests [....]

3) The Fight against Jewry

It was to be expected from the beginning that the Jewish problem in

the Ostland could not be solved by pogroms alone. At the same time, the

Security Police had basic, general orders for cleansing operations aimed

at a maximum elimination of the Jews. Large-scale executions were therefore

carried out in the cities and the countryside by Sonderkommandos [Special

Killing Detachments], which were assisted by selected units of partisan

[nationalist] groups in Lithuania, and parties of the Latvian Auxiliary

Police in Latvia. The work of the execution units was carried out smoothly.

Where Lithuanian and Latvian forces were attached to the execution units,

the first to be chosen were those who had had members of their families

and relatives killed or deported by the Russians.

Particularly severe and extensive measures became necessary in Lithuania.

In some places—especially in Kovno—the Jews had armed themselves and took

an active part in sniping and arson. In addition, the Jews of Lithuania

cooperated most closely with the Soviets.

The total number of Jews liquidated in Lithuania is 71,105.

During the pogrom 3,800 Jews were eliminated in Kovno and about 1,200

in the smaller cities.

In Latvia, too, Jews took part in acts of sabotage and arson after the

entry of the German Wehrmacht. In Dünaburg [Dvinsk, Daugavpils] so

many fires were started by Jews that a large part of the city was destroyed.

The electric power station was burned out completely. Streets inhabited

mainly by Jews re- mained untouched. Up to now 30,000 Jews have been executed

in Latvia. The pogrom in Riga eliminated 500.

Most of the 4,5000 Jews living in Estonia at the start of the Eastern

campaign fled with the retreating Red Army. About 2,000 stayed behind.

In Reval [Tallinn] alone there were about 1,000 Jews.

The arrest of all rnale Jews over the age of sixteen is almost completed.

With the exception of the doctors and the Jewish Elders appointed by the

Sonderkommando they [the remaining Jews] are being executed by the Estonian

Self-Defense Force under the supervision of Sonderkommando Ia. Jewesses

between the ages of sixteen through sixty in Reval and Pernau, who are

fit for work, were arrested and used to cut peat and for other work.

At present a camp is being built at Harku in which all the Jews in Estonia

will be sent, so that in a short time Estonia will be cleared of Jews.

After carrying out the first large-scale executions in Lithuania and

Latvia it became clear that the total elimination of the Jews is not possible

there, at least not at the present time. As a large part of the skilled

trades is in Jewish hands in Lithuania and Latvia, and some (glaziers,

plumbers, stove-builders, shoe- makers) are almost entirely Jewish, a large

proportion of the Jewish craftsmen are indispensable at present for the

repair of essential installations, for the reconstruction of destroyed

cities, and for work of military importance. Although the employers aim

at replacing Jewish labor with Lithuanian or Latvian workers, it is not

yet possible to replace all the Jews presently employed, particularly in

the larger cities. In cooperation with the labor exchange offices, however,

Jews who are no longer fit for work are picked up and will be executed

shortly in small Actions.

It must be also noted in this connection that in some places there has

been considerable resistance by offices of the Civil Administration against

large- scale executions. This [resistance] was confronted in every case

by pointing out that it was a matter of carrying out orders [involving]

a basic principle.

Apart from organizing and carrying out the executions, preparations

were begun from the first days of the operation for the establishment of

ghettos in the larger cities. This was particularly urgent in Kovno, where

there were 30,000 Jews in a total population Of 115,400. At the end of

the early pogroms, therefore, a Jewish Committee was summoned and informed

that the German authorities had so far seen no reason to interfere in the

conflicts between the Lithuanians and the Jews. A condition for the creation

of a normal situation would be, first of all, the creation of a Jewish

ghetto. When the Jewish Committee remonstrated, it was explained that there

was no other possibility of preventing further pogroms. At this the Jews

at once declared that they were ready to do everything to transfer their

co-racials as quickly as possible to the Vilianipole Quarter [Slobodka],

where it was planned to establish the Jewish ghetto. This area is situated

in the triangle between the River Memel and a branch of the river, and

is linked with Kovno by only one bridge, and therefore easily sealed off.

In Riga the so-called Moscow Suburb was designated as the ghetto. This

is the worst residential quarter of Riga, which is already inhabited mainly

by Jews. The transfer of Jews into the ghetto area proved rather difficult

because the Latvians living in that district had to be evacuated and residential

space in Riga is very crowded. Of about 28,000 Jews remaining in Riga,

24,000 are now housed in the ghetto. The Security Police carried out only

police duties in the establishment of the ghetto, while the arrangements

and administration of the ghetto, as well as the regulation of the food

supply for the inmates of the ghetto, were left to the Civil Administration;

the Labor Office was left in charge of Jewish labor.

Ghettos are also being set up in other cities in which there are a large

number of Jews [....]

(signed) Stahlecker

SS-Brigadeführer and Major-General of Police

Source: Nuremberg Documents L-180

Bibliography:

Arad, Yitzhak, Shmuel Krakowski, and Shmuel Spector, eds. The Einsatzgruppen

Reports: Selections from the Dispatches of the Nazi Death Squads' Campaign

Against the Jews in Occupied Territories of the Soviet Union, July 1941-January

1943 (New York: Holocaust Library, 1989).

Headland, Ronald. Messages of Murder : A Study of the Reports of

the Einsatzgruppen of the Security Police and the Security Service, 1941-1943

(Rutherford [N.J.]: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press ; London: Associated

University Presses, 1992)

Krausnick, Helmut and Hans-Heinrich Wilhelm. Die Truppe des Weltanschauungskrieges

: die Einsatzgruppen der Sicherheitspolizei und des SD, 1938-1942 (Stuttgart:

DVA, 1981).

Trials of War Criminals Before the Nuremberg Military Tribunals

under Control Council Law No. 10, Nuremberg, October 1946-April, 1949 (Washington,

D.C.: GPO, 1949-1953), vol. 4, Case 9: U.S. v. Ohlendorf (The Einsatzgruppen

Case).

Wilhelm, Hans-Heinrich. Die Einsatzgruppe A der Sicherheitspolizei

und des SD 1941/42 (Frankfurt am Main: P. Lang, 1996)

Return

to 443/543 Homepage