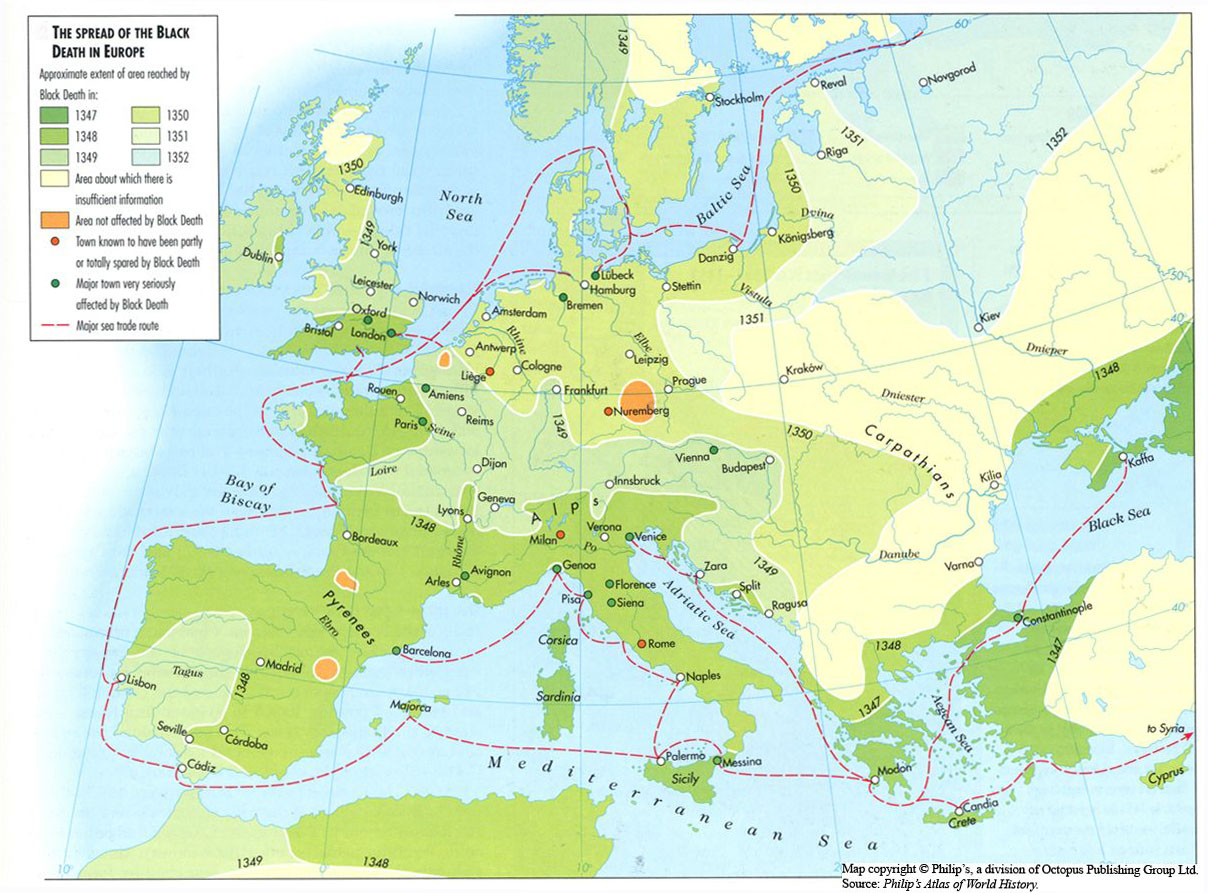

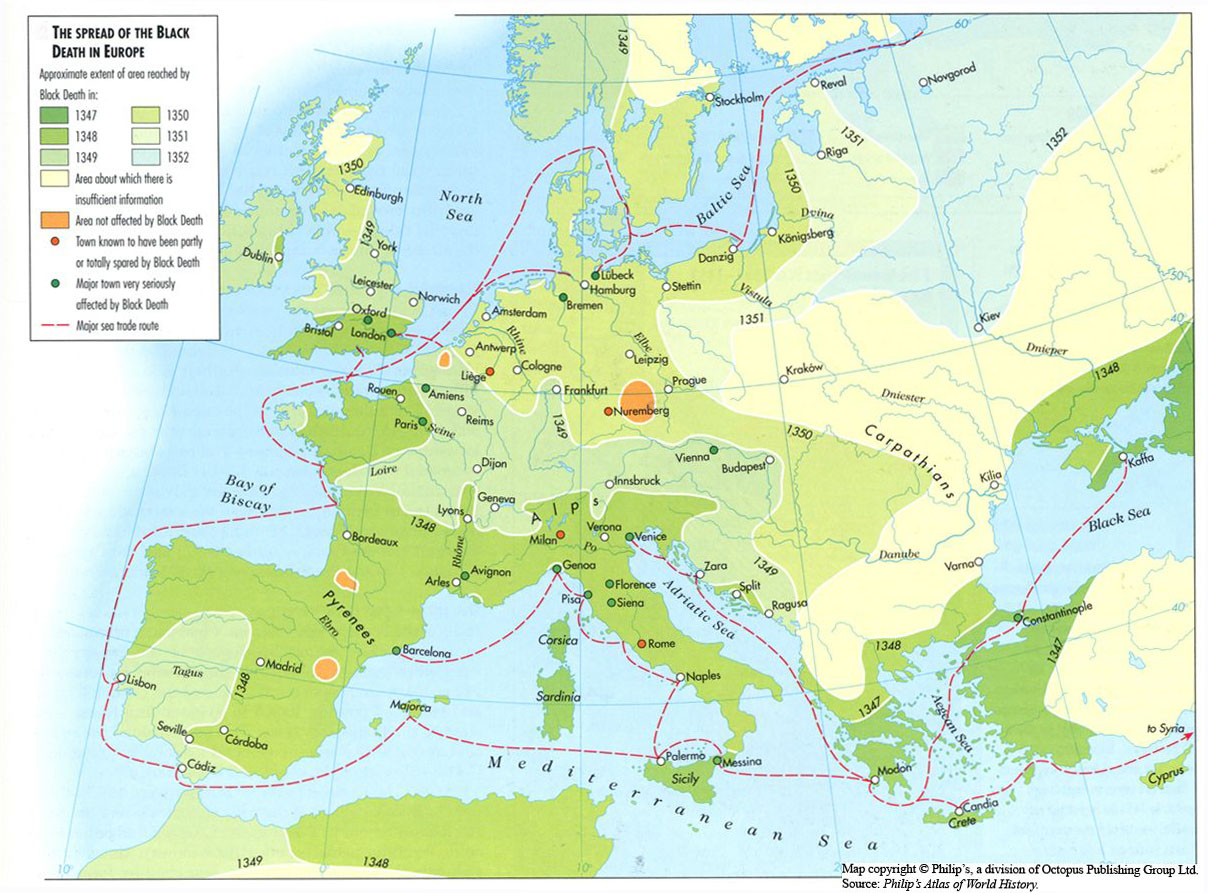

The Spread of Plague

The exact cause of plague and the vector of its

entry into the human population remains subject to debate. The dominant interpretation

remains that of William McNeil and others who hold that it was caused by the bacillus

Yersinia pestis, the same microbe that caused a rat-based epidemic in South

Asia in the 1890s.[1] That

thesis has recently been challenged on the grounds that in certain crucial respects,

the pattern of infection and mortality in 1347-1351 differed sharply from the

epidemiology of Yersinia pestis.[2]

This argument begs the question of coevolution, for it is to be expected that

a disease agent as deadly as the one which killed off a third of Europe's population

within a few years would mutate in the process. More secure is the path that Plague

took in spreading across Europe. Here is how a contemporary, Giovanni Villani,

described how the disease entered Europe from Asia:

[Having spread] over the whole

[Near East] and Mesopotamia and Syria…the pestilence leaped to Sicily, Sardinia,

and Corsica and Elba, and from there soon reached all the shores of the mainland.

And of eight Genoese galleys, which had gone to the Black Sea, only four returned,

full of infected sailors, who were smitten one after another on the return journey.

And all who arrived in Genoa died, and they corrupted the air to such an extent

that whoever came near the bodies died shortly thereafter….And the priest who

confessed the sick and those who nursed them so generally caught the infection

that the victims were abandoned and deprived of confession, sacrament, and medicine,

and nursing…And many lands and cities were made desolate. And the plague lasted

until....

...Villani left a blank here, intending to record

when the Black Death ended; but he, too, died of the disease.[3]

The

Human Cost of Plague: Barcelona, 1348-1653

This chart depicts the number of plague-induced deaths in the Barcelona between

the first outbreak in 1348 and until the great outbreak in that city in 1653.

It illustrates the long-term impact of epidemic disease on urban populations:

the cumulative effect was to keep Barcelona's population suppressed below pre-plague

levels for two hundred years, until the middle of the sixteenth century. Then

the 1653 epidemic struck, with consequences almost as drastic. It's important

to keep two things in mind when thinking about these numbers, however. The first

is that Barcelona, a major seaport on the Mediterranean coast, was like other

trading centers more exposed to outbreaks of plague and other forms of epidemic

disease than inland towns or rural districts were. On the other hand, it is likely

that large numbers of people move intoBarcelona after the 1348 pandemic,

which probably compensated for some of the drop in population. If that is so,

the number of deaths caused by plague in 1348-49 was greater than it appears

on this chart.[4]

Child Mortality and Plague: Siena, 1348-1400

This chart describes vividly the special vulnerability of children to the ravages

of plague in the late fourteenth century. The data come from records of the Dominican

cemetery in Siena, Italy, where precise accounts were kept of who was buried and

their age at death. The bear witness to a remarkable transformation in the pattern

of plague mortality: of 136 people buried in the Dominican cemetery in 1348, the

year of the first outbreak, the overwhelming majority were adults; not quite 9%

were children. Over the next three decades, that ratio was reversed: already in

1363, the proportion of young people killed by plague had risen so sharply as

to earn it the label pestis puerorum--the children's plague. Accordingly,

children made up 35% of the total number buried in the Dominican cemetery. The

apex of child mortality came in 1383, when 88.5% of the buriedvictims were children.[5]

[1] William H. McNeil, Plagues and Peoples (New York: Doubleday,

1977); Philip Ziegler, The Black Death (New York, John Day, 1969); Robert

Gottfried, The Black Death: Natural and Human Disaster in Medieval Europe

(New York: Free Press, 1983).

[2] Samuel K. Cohn, Jr., “The Black Death: The End of a Paradigm,”

American Historical Review 107/3 (2002): 703-738.

[3] Quoted in Gottfried, The Black Death, 53.

[4] Source for data: Jean Noël Biraben, Les hommes et la

peste en France et dans les pays européens et méditerranéens

(Paris: Mouton, 1975).

[5] Source for data: Cohn, “The Black Death: The End of a Paradigm.”

Return

to 441 Homepage