The

Liturgical Calendar

The

Liturgical Calendar

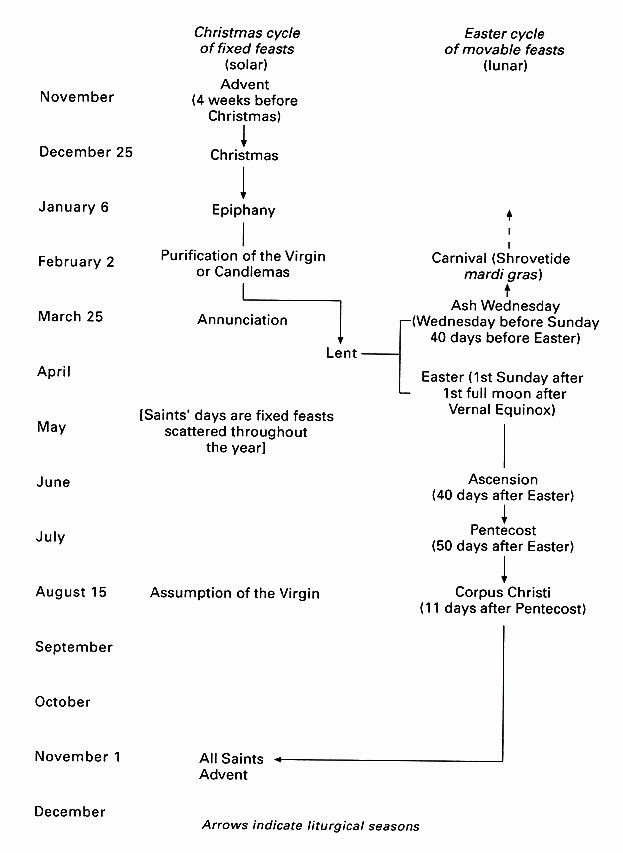

The Christian liturgical year was founded on three basic structures:

1) The Nativity

Cycle, reckoned from the twenty-fifth day of

the tenth month of the Julian solar year;

2) The Easter Cycle of movable feasts, derived from the lunar

dating of the Jewish Passover;

3) The Annual Round of Saints' Days, culminating on November

1 with All Saints'.

The main sequence of liturgical occasions was built around elements of all three. This was the cycle of events that re-enacted the great mysteries of Christian belief, the Incarnation, ministry, and Resurrection of Christ. The annual round began with Advent, a season devoted to commemorating the Incarnation, which began four Sundays before Christmas (December 25). The Christmas season itself lasted twelve days until the Feast of the Epiphany, January 6 (in the Roman reckoning); in the midst of this period fell the carnevalesque revelries that took place on the Feast of the Circumcision (January 1).

A second phase began on January 20 and centered on the Feast of the Purification of the Virgin, or Candlemas, on February 2. As Edward Muir writes,

This season connected the pure fertility of the Virgin, who gave birth to the light of the world, to the onset of spring...with its promise of the regeneration of nature. In some ways an amalgam of the pagan Feast of Lights (February 1) and the Roman Lupercalia (February 15), the Christian purification rituals retained associations with lustration, fire symbolism, and fertility. The central images of the season involved the rising sap in plants and the lengthening of the day, symbolized by the blessing of candles on Candlemas, an appropriate image since the seasonal work now shifted from indoor tasks to the first outdoor ones [Ritual in Early Modern Europe, 62].Despite or perhaps because of these associations, Candlemas was also an occasion for the magical empowerment of ordinary parishioners against hostile and evil forces: the blessed candles were distributed among the churchgoers, who used them for various apotropaic or even maleficent purposes. In England, for example, witches were said to drop blessed candle wax into the footprints of enemies, causing their feet to rot off [Duffy, Stripping the Altars, 18].

The highpoint of the liturgical season, of course, was the lunar-based Easter Cycle, which began Ash Wednesday, always 40 days before Easter itself. This cycle commemorated the central events of Christian belief: the Last Supper, Crucifixion, and Resurrection; as a lunar event, Easter fell on any Sunday between March 22 and April 25. Ash Wednesday inaugurated Lent, the season of fasting, prayer, and penance, leading up to Holy Week, which was filled with sacred performances commemorative of the Passion. On Maundy Thursday, for example, a priest washed the feet of twelve parishioners, in commemoration of the Christ washing the feet of the Apostles; Good Friday was observed with a ceremonial “burial” of the crucified Christ in a sepulchre:

At the end of the liturgy on Good Friday, the priest put off his Mass vestments and, barefoot and wearing his surplice, brought the third Host consecrated the day before, in a pyx. The pyx and the cross which had been kissed by the people during the liturgy were wrapped in linen cloths and taken to the north side of the chancel, where a sepulchre had been prepared for them....The host and crucifix were placed within it while the priest intoned the Psalm verse, "I am counted as one of them that go down to the pit," and the sepulchre was censed [Duffy, Stripping the Altars, 30].Easter itself was filled with ceremonial renactments of the resurrection; it was also the one day of the year on which most parishioners took communion. For Eamon Duffy, all these rituals imply a great deal about lay religious sophistication: Symbolic enactments of Christ's death and resurrection conveyed the central doctrines of Christianity to the widest possible lay audience, involving them performatively in a process of internalization.

Easter inaugurated a fourth liturgical season: forty days of rejoicing follwed Easter, just has forty days of fasting had preceded it, ending on Ascension Day. The last of the lunar festivals was Pentecost in June, but in the late Middle Ages it was overshadowed by the new Feast of Corpus Christi, celebrated eleven days later. On this occasion, the consecrated host was carried outside the church on procession through the parish amid elaborate parades and tableaux vivants.

The year was also punctuated throughout by Saint's days, though these were clustered more densely in the second half, after the main cycle of liturgical commemoration had concluded. The most widely observed were festivals associated with the Virgin Mary, John the Baptist, and the Twelve Apostles. The former included festivals of the Purification (February 2), the Annuncation (March 25), the Visitation (July 2), the Assumption (August 15), the Birth of Mary (September 8), her Presentation (November 21) and her Conception (December 8).Image source: Edward Muir, Ritual in Early Modern Europe (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997), 59.