|

History 102

Western Civilization (II) |

Was there a media revolution in fifteenth-century

Europe?

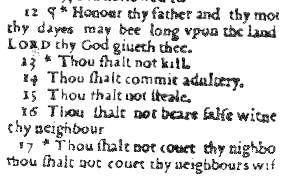

Image: “Wicked Bible” of 1631

In 1620, the Lord Chancellor of England, Francis Bacon, remarked—in

the flowery language of his age—on how technology had shaped his times:

We should note the force, effect, and the

consequences

of inventions which are nowhere more conspicuous than in those three

which

were unknown to the ancients, namely, printing, gunpowder, and the

compass.

For these three have changed the appearance and state of the whole world.

Did the invention of moveable block type bring about a “media

revolution”

in fifteenth-century Europe? Those historians who do insist that

the

new method of producing image and text fundamentally changed the

relationship

between people and information and revolutionized European culture in

the

process. Their argument goes something like this:

1) Printing may have been in the process of “discovery” in

several

places at once; but the first to develop the technology to its full

potential

was Johannes Gutenberg, a goldsmith in the German city of Mainz,

sometime

in the 1440s.

-

A shrewd businessman, Gutenberg published the first printed

Bible in

1455, with 42 lines per page; thanks in part to Gutenberg’s own

promoting,

the technology spread swiftly from Mainz to other European cities.

-

Strasbourg (1460) quickly became a leading center of

European publishing;

Rome

(1462),

Basel in Switzerland (1466), Utrecht in the

Netherlands (1470),

Paris (1470), Budapest (1473), Cracow

in Poland (1474);

London (1476) all followed soon after.

-

But the technique took hold most in Italy: by 1500, the city

of

Venice had 150 presses.

Most of the major forms of the modern book were invented during the

first fifty years of “print culture”:

-

The first printed illustrations were introduced in 1461—by

incorporating

woodcuts on a page of type.

-

Nicolas Jenson and Aldus Manutius developed the Roman typeface in 1470;

-

Manutius also invented Italic typeface and produced the first

“pocket

editions”;

-

A French press published the first “luxury edition” (1481);

-

It became customary for publishers to identify themselves on titlepages

as a means to prevent pirating; etc.

But these only describe the superficial elements of the “Media

Revolution.”

As

a cultural phenomenon, advocates of the "media revolution" thesis

emphasize

two major effects of printing on information: dissemination

and

standardization.

2) Dissemination: printing put more information into more

hands

at a lower cost than ever before. Any purchaser of books was now able

to

buy more books at a lower cost; the effect was simply an increase

in

the sheer volume of information being disseminated.

-

Now, most of this information was not particularly new material;

even so, simply by increasing the amount of text in circulation, even

though

most of it was not new, printing helped to enrich the European “diet”

of

information and knowledge.

What may not be so obvious is that this rearranged the

relationship

between books and their readers: before the advent of the printed

book,

readers

went to books; with publishing, increasingly, books went to

readers.

It is difficult to exaggerate the magnitude of this change. Consider

this: In 1503, a fifty-year-old woman could look back on her lifetime

and

observe that over 9,000,000 books had been printed since her birth in

1453.

This was a larger number, in all probability, than had been copied by

all

the scribes in all of Europe in all the centuries since the collapse of

the Roman Empire.

What were some of the effects of this explosion in the volume of

text in circulation?

a) Expanded Horizons:

In the long run, though, increased volume of information also broadened

the mental horizons of Europe’s readers. Libraries got bigger, and

bigger

libraries offered more occasion for comparing texts and other forms of

information storage, such as maps.

-

Perhaps the most vivid illustration of this was a proliferation of

so-called

“Polyglot Bibles”: Bibles published in all their most ancient

original

languages, side-by-side.

-

The climax of Polyglot Bibles was the London Polyglot of 1657, with

parallel

texts in “Hebrew, Samaritan, Septuagint Greek, Chaldee, Syriac, Arabic,

Ethiopian, Persian and Vulgate Latin” (this, according to a prospectus

for the book).

-

Some historians believe that dissemination also encouraged more

cross-cultural

comparison, too, which may help explain the sixteenth- and

seventeenth-century

fascination with alchemy, Arabic astrology and astronomy, with the

Jewish

Kabala and other forms of mysticism.

b) Propaganda and Censorship:

Established authorities, including the Church, initially encouraged

printing—the papacy, in particular, was instrumental in introducing

printing

to Italy in the early 1460s. The first best-seller was a devotional

work

by Thomas à Kempis, The Imitation of Christ, which went

through

99 editions between 1471 and 1500. But political authorities were

relatively

quick to recognize the dangerous potential of an unfettered flow of

information:

-

The German city of Cologne started censoring printed books

already

in 1487;

-

In the 1520s, the Protestant Reformation exposed the disruptive

potential

of printing; the historian A.G. Dickens described the impact of

printing

this way:

Between 1517 and 1520, [Martin] Luther’s thirty

publications

probably sold well over 300,000 copies…[and it] seems difficult to

exaggerate

the significance of the [printing] press, without which a revolution of

such a magnitude could scarcely have been [achieved]. Unlike [earlier]

heresies, Lutheranism was from the first a child of the printed book,

and

through this vehicle Luther was able to make exact, standardized, and

ineradicable

impressions on the mind of Europe. For the first time in human history,

a great reading public judged the validity of revolutionary ideas

through

a mass-medium which used the vernacular language.

- Some Reformers came to regard printing as a sign of God’s special

favor

on the Reformers: according to the sixteenth-century Protestant

historian,

Johann Sleidan:

As if to offer proof that God has chosen us to

accomplish

a special mission, there was invented in our land a marvelous new and

subtle

art, the art of printing. This opened German eyes even as it now is

bringing

enlightenment to other countries. Each man became eager of knowledge,

not

without feeling a sense of amazement at his former blindness.

- During the Reformation, authorities tried to restrict the

dissemination

of printed texts, especially “heretical” texts: the city of

Strasbourg

began censorship with a ban on a satire of Martin Luther in 1522;

before

long, Reformed cities would begin censoring Catholic tracts, and so on.

All this was before the Catholic Church established the “Index of

Prohibited

Books” in 1543.

3) Standardization: the second element of the “Media

Revolution”

involved the standardization of knowledge. The idea is simply this: printing

had the effect of fixing texts, of enhancing their permanence. At

the

same time, however, the vastly increased volume of knowledge in

circulation

through books raised the question of authority. A few examples:

a) Norming Text: Printing reversed the relationship between

multiplication

and error:

-

Under the scribal regime, the risk that a mistake might get

introduced

into a text increased every time a book was copied. The more

copies

made, the more mistakes. One result of this was that texts tended to “drift”—as

mistakes of transcription were copied and recopied into later versions

of the original.

-

In “print culture,” multiplication was the guarantee of

accuracy: printing

drew attention to errors by mass-producing them, and also made the

“accurate”

text easier to specify. Consider the “Wicked Bible” of 1631, which

omitted the word “not” from the Seventh Commandment!

b) Norming Language: Another effect of the preservative power

of

printing through the multiplication of identical texts was to standardize

language: prior to the sixteenth century, there was really no such

thing as “orthography,” not even in Latin.

-

The sixteenth century was one of dictionaries in most of the

major languages

in Europe; but these dictionaries were not so much recording an

existing

vocabulary but in the business of establishing and standardizing

one.

-

This, in turn, tended to codify existing or emerging linguistic

divisions:

to cite but one example, in the fifteenth century it made little sense

to speak of “Dutch” or “German” as sharply distinct languages. Rather,

there was a continuum of dozens of related spoken dialects from Flemish

in the west to Saxon and Prussian in the east and Bavarian in the

south.

But

by the end of the sixteenth century, Dutch had become a clearly

distinct,

literary language.

-

It would be an exaggeration to say that England became English

during

the sixteenth century, and because of printing; but there is little

doubt that printing fixed a “standard” of spelling and grammar in

“authoritative”

English.

c) Standardizing Culture: It is no accident that the terms

“stereotype”

and “cliché” come from the vocabulary of mechanical

type-setting:

the broadcasting of new ideas in print also encouraged certain

forms

of standardization in culture.

-

Take international fashion: for the first time, it was

possible

to publish identical sewing patterns, with the result that a Sicilian

and

a Scot could wear virtually identical clothing. Indeed, it is during

the

sixteenth century that Europe acquired an international culture of

clothing

fashion (among the very wealthy, to be sure).

-

By the same token, print culture tended to amplify and reinforce

ideas:

it would be exaggerated to say that printing “caused” the formation of

national or ethnic stereotypes—these have always existed. But it may

well

have reinforced them

Return

to homepage