Liturgy

and Folklorized Ritual: Sacramentals and functiones sacrae

Liturgy

and Folklorized Ritual: Sacramentals and functiones sacrae

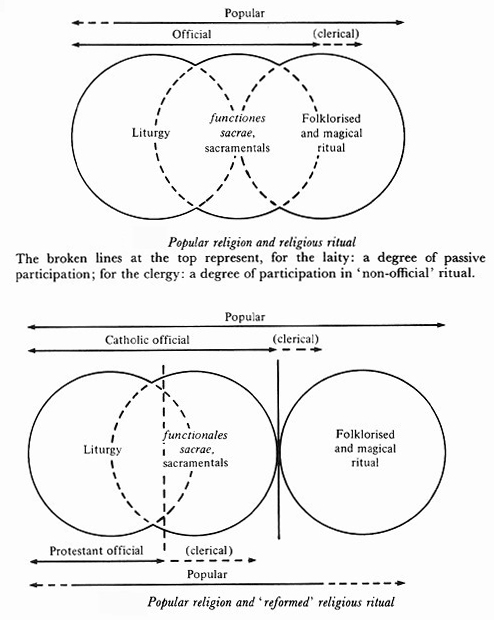

One way to explore the relationship between "official" and "popular" religion in late medieval and early modern Europe is to focus on liturgical objects and their uses. The central act of any festival in the liturgical calendar was, of course, celebration of the Mass. During the two hundred years prior to the Reformation, this rite consisted of the following principal elements: an introductory psalm; the announcement of redemption in the hymn Gloria; declarations of faith and readings from the Gospels and Epistles; the offertory, or collection from the congregation; the canon, or rite of communion; and concluding rituals, including the benediction. At several points in its celebration, the Mass was interrupted by processions around the church, accompanied by singing of the Salve, during which the congregation was incensed or sprinkled with holy water. Saints' relics in their monstrances might be placed on the altar or carried among the congregation; each Sunday there was a blessing of Holy Water. The official liturgy was also surrounded by a cloud of semi-liturgical performances, such as the public procession of wooden effigies of Christ, seated on an ass, through the parish on Palm Sunday, or the 'laying of Christ in the grave' on Good Friday. Robert Scribner describes these performances as "folklorized ritual": they touched on the official liturgy at several points, but also extended it. Common to both spheres--official liturgy and "folklorized ritual"--were the "sacred actions" (functiones sacrae or actiones sacrae) of the church: sacred re-enactments of the life of Christ and the mysteries of the church.

As this outline suggests, "sacred functions" involved the manipulation of words and objects, ritual performances which gave those words and objects great power. Popular magical beliefs and practices readily attached to these words and objects, which was a matter of some concern: in the wrong mouths, the words of the canon might be used for conjuring or witchcraft. Into this paraliturgical gray zone fell a class of words and objects called "sacramentals," which derived their power from the blessing of a priest or use in a sacred performance, but were put to all sorts of magical uses. For example, herbs blessed on the Feast of the Assumption of the Virgin (August 15) were commonly used for magical purposes. Another good example is "Blasius Water"--holy water blessed on the Feast of Saint Blasius (February 3), which was believed to be especially effective for curing throat infections. Water blessed on the Feast of Saint Stephen (December 26) protected cattle from sickness, but could also be used to ward off danger to humans. Among the most powerful were objects associated with performance of Mass. As Scribner notes,

Objects laid under the altar while mass was being celebrated...were held to acquire healing power. Looking into the chalice after mass was believed to be a cure for jaundice. The altar clorth and the corporal upon which the consecrated host was placed during the mass were also believed to acquire healing power by sympathy. The former could cure epileptics, the latter was good for eye illness...The corporal was also held to be effective in extinguishing fires, a sympathetic extension of the power of the consecrated host, which was held to have the same power, on to the object on which it had rested during the mass (Scribner, "Ritual and Popular Religion").The apotropaic (i.e. protective) or curative powers of these words and objects occupied a "twilight zone," as Scribner calls it, with no sharp boundaries between ecclesiastically sanctioned ritual, on the one side, and popular instrumental magic on the other side, even though the fundamental assumptions governing these spheres were quite different. Official liturgy was spiritually effective independently of the celebrant's inner state: a sinful priest could still perform a rite that guaranteed grace. The popular tendency was to treat sacramentals the same way. At issue between these positions was a question of agency: whether the ordained priesthood enjoyed a monopoly over human manipulation of the divine power through ritual.