|

|

|

|

The notion that the Cosmological Constant is nonzero is based on the idea that the vacuum can contain energy! In the vacuum, we know that fluctuations occur; in vacuum we find virtual pairs of particles spontaneously popping into and out of existence. The virtual pairs of particles (composed of a particle and its anti-matter twin) cannot be measured directly but their effects on the world can be measured and they can affect the evolution of the Universe.

The bizarre notion that virtual pairs can just appear and disappear in vacuum has, in fact, been experimentally verified. The Casimir Effect has been observed. This occurs when two uncharged metal plates attract each other through the electromagnetic force, if they are placed close enough. This is odd. There is also something known as the Lamb Shift. The structure of a hydrogen atom (note atoms are held together by the electromagnetic attraction between the positively charged protons in their nuclei and the negatively charged electrons surrounding the nuclei) is found to be slightly altered by the appearance and disappearance of virtual pairs of particles. The seemingly odd notion of spontaneous creation and destruction of particle pairs in vacuum is experimentally verified.

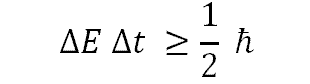

Strangely enough, it doesn't. In a quantum mechanical world, we cannot measure both the position and momentum of a particle to absolute precision simultaneously. At a given time, there is always an uncertainty as to where a particle resides and how much momentum it carries. The relationship between the uncertainty in the time when a particle exists and how much energy it carries during this time is also given by the Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle,

The above gives the energy formulation of the Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle. There is always an uncertainty in how much energy an object carries and when the object has that energy. Virtual pairs of particles can thus fluctuate into existence and if they subsequently annihilate fast enough, no conservation laws are violated because we cannot say for sure that they were there. If the fluctuation involves only a small energy, then it can exist for a long time.

|

The production of virtual pairs of particles occurs spontaneously everywhere in the vacuum. What are the implications of this? Look at the panel to the left, as the piston pulls out of the cylinder (moves to the right), the number of virtual pairs grows as the vacuum grows. That is, as the volume grows, the energy (and therefore mass) of the vacuum get larger! This is strange and oppostite to what happens with a normal gas. When a normal gas expands, it cools, becomes less dense, and its pressure goes down; the pressure performs work (and loses energy) as it pushes the piston outward. For a vacuum, as the piston moves outward, the energy increases because the density of pairs remains the same. This is odd and technically means that the pressure associated with the vacuum is negative ===> its effective mass is negative and so the vacuum acts like anti-gravity. Such vacuum energy may be the controlling force in the current evolution of our Universe! |

Yes, we can offer simple arguments to show how this should work. The appearance and disappearance of virtual pairs of particles must not be observable and so, this sleight of hand must take place over a small region, technically measured by something known as the Compton wavelength, the size of the region over which we cannot precisely pinpoint the location of a particle. So, Virtual Pairs of particles that form in vacuum, arise in boxes which are roughly the size of their Compton wavelengths. This allows us to estimate the density of Virtual Pairs of a given particle. If we then sum up the contribution to the vacuum from all of the known kinds of particles, an estimate for the Dark Energy can be made. Annoyingly, the estimate is wildly inconsistent with data. The

predicted to observed dark energy = 10120

Ooops! This is not good even by astrophysical standards. In order to bring the observed Cosmological Constant and its theoretical estimate into line requires that fluctuations in the vacuum be arranged so that there there is some fierce cancellation going on. The fierceness of the cancelation can be seen from the following argument. If we produce particles in such a way that the individual particles cancel each other out, then even though we make pairs, there is no overall effect. The fact that our estimate misses by 10120 means that for every 10120 virtual pairs that form and cancel, there is one fluctuation which does not cancel. This odd fluctuation is the one that leads to the dark energy of the Universe. This is fierce cancelation and represents fierce fine-tuning.