23 JUNE 2016 | VOL 534 | NATURE | 515

Let ter

reSeArCH

(M

tot,z

= (1 + z)M

tot

) and taking into account the advanced O1 hori-

zon redshift for this most massive binary (z = 0.7), the highest possible

observed mass within O1 would be approximately 240M

⊙

.

Spin magnitudes and directions of merging black holes are poten-

tially measurable by LIGO

1

. The second-born black hole in a BH–BH

binary does not accrete mass, and its spin at merger is unchanged

from its spin at birth. The first-born black hole, on the other hand,

has a chance to accrete material from the stellar wind of the unevolved

companion or during common-envelope evolution. However, because

this is limited either by the very low efficiency of accretion from

stellar winds or by inefficient accretion during common-envelope

evolution

26,27

, the total accreted mass onto the first-born black hole

is expected to be rather small (about 1M

⊙

–2M

⊙

). This is insufficient

to significantly increase the spin, and thus the spin magnitude of the

first-born black hole at merger is within about 10% of its birth spin.

In our modelling, we assume that stars that are born in a binary have

their spins aligned with the angular-momentum vector of the binary.

If massive black holes do not receive natal kicks (for example, in our

standard model M1), then our prediction is that black-hole spins are

aligned during the final massive BH–BH merger. We note that our

standard model includes natal kicks and mass loss for low-mass black

holes (less than about 10M

⊙

), and therefore BH–BH binaries with one

or two low-mass black holes may show misalignment. Alternatively,

binaries could be born with misalignment and retain it, misalignment

could be caused by the third body or by interaction between the radia-

tive envelope and the convective core

28

, or misalignment could result

from a large natal kick on the second-born black hole. Several binaries

are reported with misaligned spins

29

. Therefore, spin alignment of

massive merging black holes suggests isolated field evolution, while

misaligned spins do not elucidate formation processes.

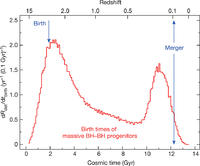

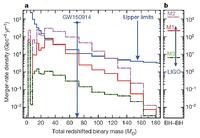

As shown in Fig. 1, we find that the formation of massive BH–BH

mergers is a natural consequence of isolated binary evolution. Our

standard model (M1) of BH–BH mergers fully accounts for the observed

merger-rate density and merger mass (Fig. 3), and for the mass ratio of two

merging black holes (Extended Data Fig. 3) inferred from GW150914.

Our standard formation mechanism (M1) produces significantly more

binary black holes than do alternative, dynamical channels associated

with globular clusters. A recent study

11

suggests globular clusters could

produce a typical merger rate of 5Gpc

−3

yr

−1

; our standard model (M1)

BH–BH merger-rate density is about 40 times larger: 218Gpc

−3

yr

−1

.

However, one non-classical isolated binary evolution channel involving

rapidly rotating stars (homogeneous evolution) in very close binaries

may also fully account for the formation of GW150914 (refs 12–15).

In particular, typical rates of 1.8 detections in 16days of O1 observations

are found

13

, which is comparable to our prediction of 2.8 (Table 1). Only

very massive BH–BH mergers with total intrinsic masses of more than

about 50M

⊙

are formed in this model

12,13

, whereas our model predicts

mergers with masses in a broader range, down to greater than about

10M

⊙

. Future LIGO observations of BH–BH mergers may allow us to

discriminate between these two very different mass distributions/models.

Online Content Methods, along with any additional Extended Data display items and

Source Data, are available in the online version of the paper; references unique to

these sections appear only in the online paper.

Received 21 February; accepted 11 May 2016.

1. Abbott, B. P. et al. Observation of gravitational waves from a binary black hole

merger. Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 061102 (2016).

2. Belczynski, K. et al. The effect of metallicity on the detection prospects for

gravitational waves. Astrophys. J. 715, L138–L141 (2010).

3. Dominik, M. et al. Double compact objects. III. Gravitational-wave detection

rates. Astrophys. J. 806, 263 (2015).

4. Belczynski, K. et al. Compact binary merger rates: comparison with LIGO/Virgo

upper limits. Astrophys. J. 819, 108 (2016).

5. Tutukov, A. V. & Yungelson, L. R. The merger rate of neutron star and black hole

binaries. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 260, 675–678 (1993).

6. Lipunov, V. M., Postnov, K. A. & Prokhorov, M. E. Black holes and gravitational

waves: possibilities for simultaneous detection using first-generation laser

interferometers. Astron. Lett. 23, 492–497 (1997).

7. Nelemans, G., Yungelson, L. R. & Portegies Zwart, S. F. The gravitational wave

signal from the Galactic disk population of binaries containing two compact

objects. Astron. Astrophys. 375, 890–898 (2001).

8. Voss, R. & Tauris, T. M. Galactic distribution of merging neutron stars and black

holes – prospects for short gamma-ray burst progenitors and LIGO/VIRGO.

Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 342, 1169–1184 (2003).

9. Belczynski, K., Taam, R. E., Kalogera, V., Rasio, F. A. & Bulik, T. On the rarity of

double black hole binaries: consequences for gravitational wave detection.

Astrophys. J. 662, 504–511 (2007).

10. Mennekens, N. & Vanbeveren, D. Massive double compact object mergers:

gravitational wave sources and r-process element production sites. Astron.

Astrophys. 564, A134 (2014).

11. Rodriguez, C. L., Chatterjee, S. & Rasio, F. A. Binary black hole mergers from

globular clusters: masses, merger rates, and the impact of stellar evolution.

Phys. Rev. D 93, 084029 (2016).

12. Marchant, P., Langer, N., Podsiadlowski, P., Tauris, T. M. & Moriya, T. J. A new

route towards merging massive black holes. Astron. Astrophys. 588, A50

(2016).

13. de Mink, S. E. & Mandel, I. The chemically homogeneous evolutionary channel

for binary black hole mergers: rates and properties of gravitational-wave

events detectable by advanced LIGO. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. http://dx.doi.

org/10.1093/mnras/stw1219 (2016).

14. Eldridge, J. J. & Stanway, E. R. BPASS predictions for Binary Black-Hole

Mergers. Preprint at http://arxiv.org/abs/1602.03790 (2016).

15. Woosley, S. E. The progenitor of GW150914. Preprint at http://arXiv.org/

abs/1603.00511 (2016).

16. Belczynski, K., Kalogera, V. & Bulik, T. A comprehensive study of binary

compact objects as gravitational wave sources: evolutionary channels, rates,

and physical properties. Astrophys. J. 572, 407–431 (2002).

17. Belczynski, K. et al. Compact object modeling with the StarTrack population

synthesis code. Astrophys. J. Suppl. Ser. 174, 223–260 (2008).

18. Fryer, C. L. et al. Compact remnant mass function: dependence on the

explosion mechanism and metallicity. Astrophys. J. 749, 91 (2012).

19. Bulik, T., Belczynski, K. & Prestwich, A. IC10X-1/NGC300X-1: the very

immediate progenitors of BH-BH binaries. Astrophys. J. 730, 140 (2011).

20. Hirschauer, A. S. et al. ALFALFA discovery of the most metal-poor gas-rich

galaxy known: AGC198691. Astrophys. J. 822, 108 (2016).

21. Bulik, T., Gondek-Rosinska, D. & Belczynski, K. Expected masses of merging

compact object binaries observed in gravitational waves. Mon. Not. R. Astron.

Soc. 352, 1372–1380 (2004).

22. Abbott, B. P. et al. The rate of binary black hole mergers inferred from

advanced LIGO observations surrounding GW150914. Preprint at

http://arxiv.org/abs/1602.03842 (2016).

23. Pavlovskii, K. & Ivanova, N. Mass transfer from giant donors. Mon. Not. R.

Astron. Soc. 449, 4415–4427 (2015).

24. Eldridge, J. J., Fraser, M., Smartt, S. J., Maund, J. R. & Crockett, R. M. The death

of massive stars – II. Observational constraints on the progenitors of Type Ibc

supernovae. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 436, 774–795 (2013).

25. Gerke, J. R., Kochanek, C. S. & Stanek, K. Z. The search for failed supernovae

with the Large Binocular Telescope: first candidates. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc.

450, 3289–3305 (2015).

26. Ricker, P. M. & Taam, R. E. The interaction of stellar objects within a common

envelope. Astrophys. J. 672, L41–L44 (2008).

27. MacLeod, M. & Ramirez-Ruiz, E. Asymmetric accretion flows within a common

envelope. Astrophys. J. 803, 41 (2015).

28. Rogers, T. M., Lin, D. N. C., McElwaine, J. N. & Lau, H. H. B. Internal gravity

waves in massive stars: angular momentum transport. Astrophys. J. 772, 21

(2013).

29. Albrecht, S. et al. The BANANA project. V. Misaligned and precessing stellar

rotation axes in CV Velorum. Astrophys. J. 785, 83 (2014).

Acknowledgements We are indebted to G. Wiktorowicz, W. Gladysz and

K. Piszczek for their help with population synthesis calculations, and to

H.-Y. Chen and Z. Doctor for their help with our LIGO/Virgo rate calculations. We

thank the thousands of Universe@home users that have provided their personal

computers for our simulations. We also thank the Hannover GW group for

letting us use their ATLAS supercomputer. K.B. acknowledges support from the

NCN grant Sonata Bis 2 (DEC-2012/07/E/ST9/01360). D.E.H. was supported

by NSF CAREER grant PHY-1151836. D.E.H. also acknowledges support from

the Kavli Institute for Cosmological Physics at the University of Chicago through

NSF grant PHY-1125897 as well as an endowment from the Kavli Foundation.

T.B. acknowledges support from the NCN grant Harmonia 6 (UMO-2014/14/M/

ST9/00707). R.O’S. was supported by NSF grant PHY-1505629.

Author Contributions All authors contributed to the analysis and writing of the

paper.

Author Information Reprints and permissions information is available at

www.nature.com/reprints. The authors declare no competing financial

interests. Readers are welcome to comment on the online version of the

paper. Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to

K.B. (chrisbelczynski@gmail.com).

Reviewer Information

Nature thanks M. Cantiello and the other anonymous

reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

© 2016 Macmillan Publishers Limited. All rights reserved