Normal Galaxies

|

|

Normal Galaxies

|

|

Galaxies are clusters of stars, gas, dust, and dark matter whose emission is dominated by the light from its stars; their spectra are sum of the individual stars. Galaxies serve as markers in our study of the structure of the Universe. They are interesting in their own right, however. Hubble developed the following morphological based on their appearance) classification scheme for galaxies. Basically, Hubble formed the classes of ellipticals, spirals, and barred spirals. In addition, there are galaxies which have disks but no arms, S0s (lenticulars), and amorphous looking things which he referred to as Irregulars. Schematically, the Hubble Tuning Fork diagram looks like

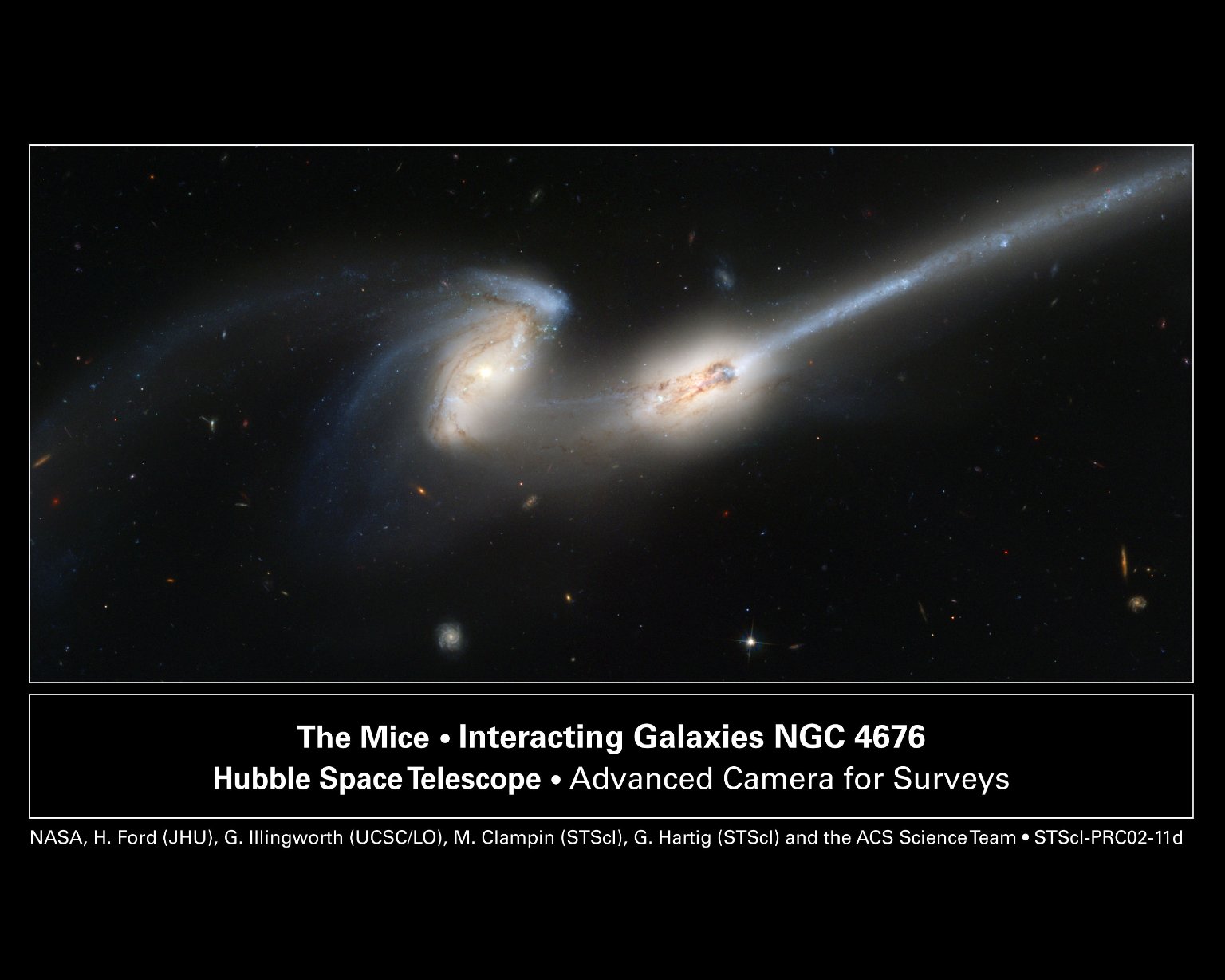

The preceding is not thought to be an evolutionary scheme. There, however, appears to be evolution between the different Hubble classes as a result of collisions between galaxies. The Milky Way galaxy is usually classified as an SBb galaxy in the Hubble scheme.

Despite the fact that the Hubble Sequence is based only on the appearance of galaxies (morphology of galaxies), several physical properties of galaxies vary smoothly along the sequence. We have,

little gas and dust <----------------------> lots of gas and dust

mainly Pop II stars <----------------------> Pop I & II stars

Reddish <----------------------------------> Bluish

little ongoing star formation <------------> star formation

large bulge <------------------------------> small bulge

tight arms <---------> loose arms

The basic idea is that either an elliptical galaxy or spiral galaxy will form depending upon when star formation occurs in the galaxy formation process. Galaxies are thought to form from the collapse of low-density gas clouds. If the gas turns into stars during the early stages of the process, then we essentially have a bunch of BBs collapsing to form the galaxy. Because stars are small and they are far apart, they don't collide in the formation process. This allows the stars to maintain roughly their initial shape and to settle into a roughly spherical form. In this case, they become elliptical galaxies.

If the gas does not turn into stars quickly, then we have a system of collapsing gas clouds. The gas clouds are much larger than are stars and collide much more readily during the formation stage. The collapsing material thus runs into opposing material as it tries to pass through the equatorial plane (for an analogous situation, consider the star formation process). The collisions do not allow the collapsing material to pass through each other and the material is forced to settle into a disk. After the disk forms, star formation begins in earnest and a spiral galaxy is produced.

|

Solar System ===> ~ 0.5 light day |

|

Galaxy Sizes (NGC 4639) ===> 0.1 Mly to 1 Mly |

|

Local Group (Andromeda, M31) ===> ~ 3 Mly |

|

Clusters (Virgo cluster) ===> ~ 10 Mly | Clusters of Clusters (Super-Clusters) ===> ~ 300 Mly |

|

Great Wall and Voids ===> 600 & 300 Mly (~ 0.6 and 0.3 Bly) |

|

|

Galaxies are often times found in rich clusters and because the Universe was smaller in the past, collisions between galaxies are likely to have been more important in the past. Collisions still occur today and will occur in the future. For example,

|

|

|

|