Keynotes 6

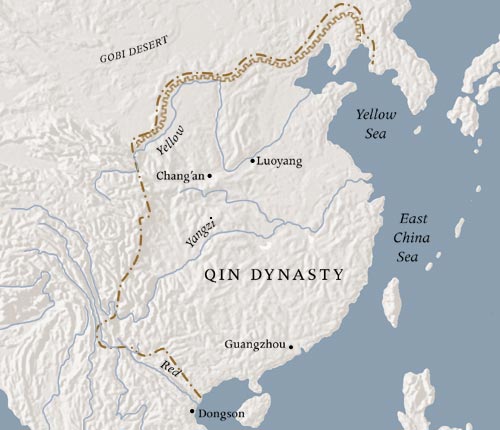

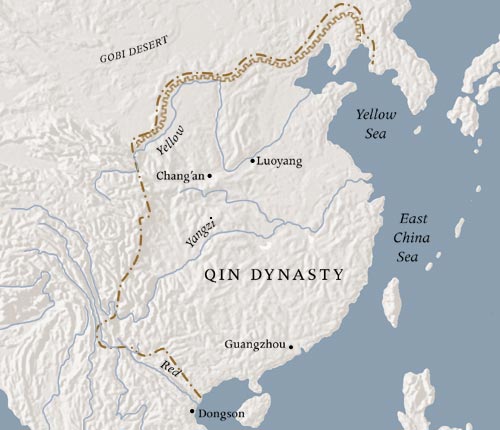

The Qin Dynasty: Political Unification Under Imperial Rule

In

221 B.C.E. China was unified under the Qin dynasty.

The basic but considerable difference between the state of Qin

and the states that had been conquered was that privileges of the nobility

were abandoned and officials who were assigned for government positions were

selected according to merits.

The nobility of the states that had been overcome by Qin had to move to the

capital Xianyang, where they lived under immediate control of the imperial

administration. The ancient feudal past came to an end and was followed by

the imperial period of Chinese history.

The state of

Qin

The

question of the best philosophy for ruling as it had been asked many times

by rulers in the Warring States period of contending powers was not asked

by the first emperor, nor was the morality of the ruler discussed. The ideology

of Legalism was based on the assumption that the nature of man is evil (first

declared by the Confucian philosopher Xunzi). Legalist philosophy considered

the strict control over the observation of laws by the people as necessary.

This ideology formed the basis of the first emperor’s rule.

More

than questions of the quality of a rule, a matter of concern discussed in

the elite circles, were how to deal with opposition and - on the other side-

how to express it, as well as how to solve economic problems and how to recruit

capable officials.

Legalist

ideas had been taken up by the Qin minister Shang Yang (his Book

of Lord Shang is dated 359 B.C.E.). Shang Yang had strengthened the state of Qin by pragmatical tax reforms and by dividing the people

into units of tens and fives who were supposed to supervise one another. The

group members were held responsible for each others' action in civil life

just as on the battlefield. With all households being registered,

tax income and recruitment for military service could easily be controlled

by the authorities. The population was divided into

20 ranks, all instantly recognizable by the color of their clothing. The amount

of land and slaves an individual could own and the style of housing was also

regulated. The land was taxed with a share of the crop.

Less

pragmatic but also inspired by legalism were the writings by Han Feizi

(280-233 B.C.E.) – the

first among the famous philosophers of ancient China whose teaching was recorded by himself

instead by his disciples. Shang Yang’s measures and Han Feizi’s ideology prepared the basis for the rule of the first

emperor. According to the teachings of Han Feizi strict laws and punishments

were the essential basis for the state to keep law and order. Education was

not a major concern of the Qin government though a certain level of qualification

was required for state positions since merit was more important than birth

in order to obtain a position in the administration. More important were agriculture

as the basis of the economy and the military to expand the territory of the

state.

In

order to consolidate his power the Qin emperor standardized

- the

script,

- weights

and measures,

- the

currency, and

- the

length of the cart axles.

- He standardized a law code which

everybody had to obey to and which prohibited the private possession of arms,

and he

- installed a state police and a secret

service as government agencies.

- Roads and canals were built to link all areas of the territory and move

soldiers and supply fast.

For

the defence of his northern border he linked the

walls that had been built by the northern states into a coherent defense system

- the Great Wall.

The Great Wall near Beijing

The

realm was divided into 42 commanderies which then

were divided into counties. Each commandery resembled

the structure of the central government: A chancellor headed the

bureaucracy, an imperial secretary drafted the emperor’s edicts, a grand commandant headed the military.

The

commanderies had three leading officials: the official in charge of tax collection, population

registers, and law and order. Another official controlled the application

of imperial edicts, and a commandant recruited and trained the military.

In

order to prevent nepotism and cliques officials were not allowed to serve

in their home town or district. Office clerks could be recruited locally.

Five

times the emperor toured his empire in the first ten years of his rule. On

these tours, he showed himself to the people and made sacrificial offerings

at the sacred mountains. Under the influence of Daoist advisors he tried

to find the means to gain immortality. Since the Eastern Sea was said to harbour

the island of the immortals he sent out ships staffed with young men and women

to search for this paradise. None of the ships returned. When he sensed that

his search for physical immortality could be in vain he increased efforts

to equip his mausoleum as a perfect mirror image of his mundane residence

as son of heaven.

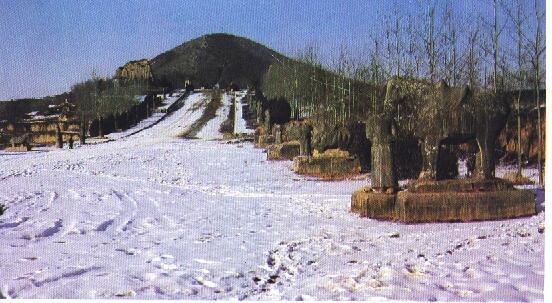

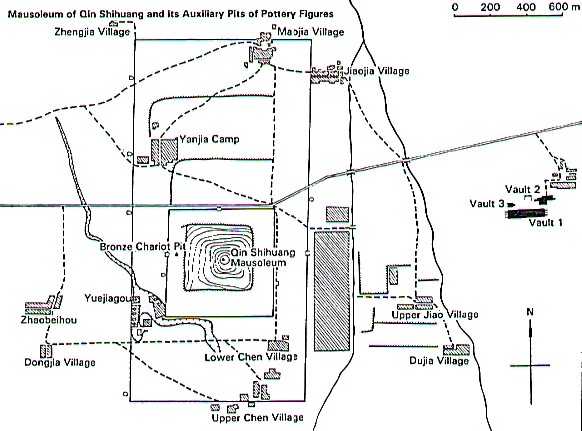

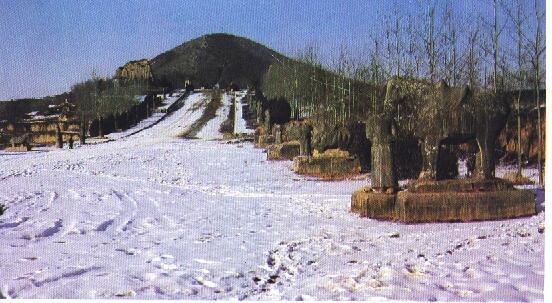

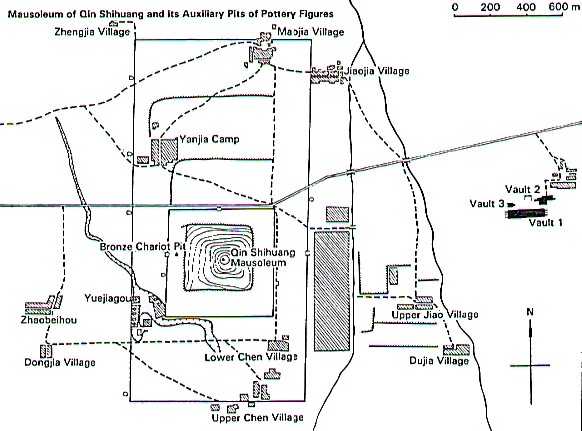

Mausoleum

of Qin Shihuang

Map of the mausoleum's

surroundings

Another

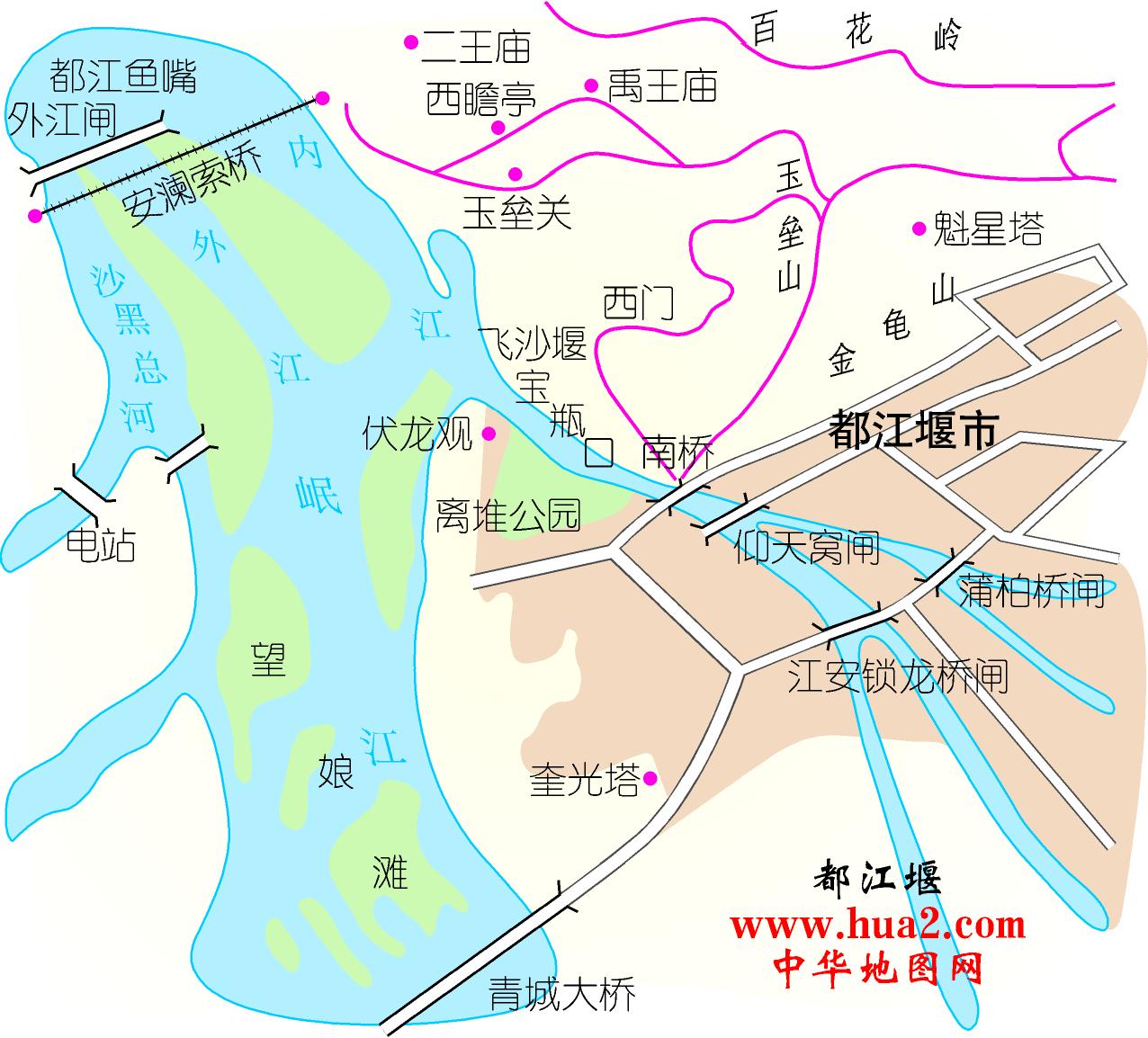

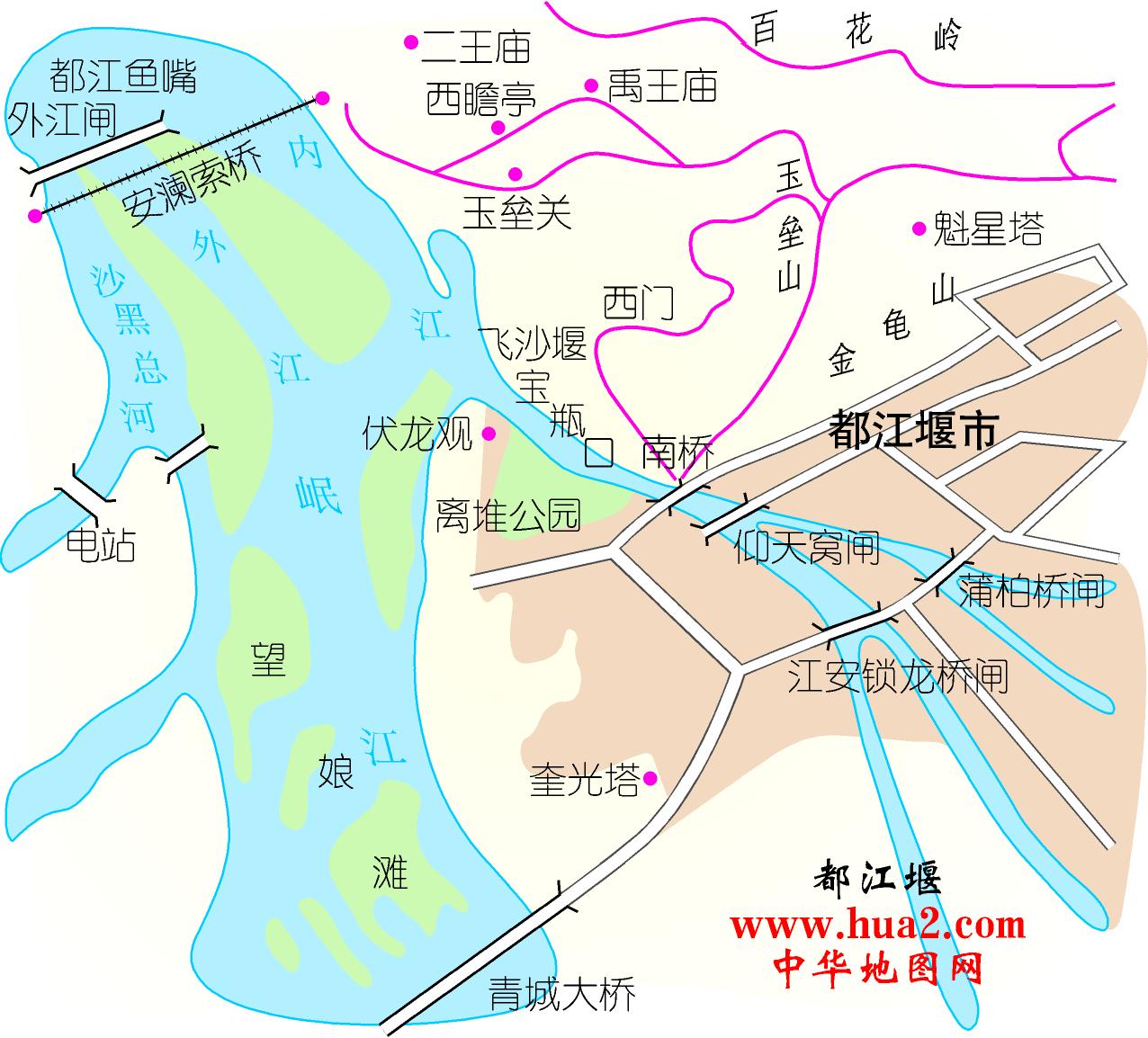

costly project which required advanced engineering techniques was the irrigation

system and the system of canals distributing the water of the Min River to

prevent Chengdu from flooding and draught. It was built by Li Bing, the governor

of Shu, and his son in the vicinity of the capital of Chengdu in Sichuan.

The division

of the Min River to control flooding and draught

The founding of the Han Dynasty

The

cruelty of Qin Shihuangdi’s rule and the costly

building projects as well as the succession to the throne by his second instead

of his first son after the first emperor's death in 210 B.C.E. provoked new

uprisings which resulted in the founding of the Han dynasty by the victorious

rebel, Liu Bang (r. 206-195 B.C.E.).

Liu

Bang, who had a peasant background, had been a supervisor of 1000 households

during the Qin and was well acquainted with Qin law. Though

attacking the Qin for its brutality, he retained

most of the laws because these laws allowed for a concentration of power in

the hands of the emperor. To ensure his popularity with the people he

lowered taxes and reduced labor services to one month per year.

One

of the measures he used to stabilize his power was to replace the leaders

of the feudal states that had re-appeared after the end of the Qin-Dynasty

by members of his own clan. In this compromise between the centralized state

of the Qin and the feudal states of Zhou-times a new arictocracy without traditional

background secured the emperor's rule over the fourteen districts which were

directly supervised by the imperial administration. In addition there were

about 150 counties or earldoms which the emperor had assigned to meritorious

officials.

The

beginning of the Han was not only threatened by interior warfare but by attacks

from the northern neighbors, the tribal confederation of

the Xiongnu. Ultimately a peace treaty was negotiated that left the

Han with the promise to send silk, food and wine to the Xiongnu

as well as a princess for the Xiongnu leader in order to keep them from raiding Han territory.

Liu

Bang was followed by empress Lü (r. 188-180)

who reigned instead of the designated successor who then was still a child.

Described as being cruel and jealous, she had four potential successors killed

in order to remain in her powerful position until her death. During her rule

she received the offer of getting married by a Xiongnu

leader. Being a widower himself he declared his intention to get married to

her, because she was widowed as well. His clever attempt to obtain power without

war was declined by Empress Lü. But she realized that her position

was challenged not only by contenders but by the despised 'barbarian' neighbors

as well.

Significant

Features of 'Han' Culture

-

Writing History

-

Introduction of 'university' exams: Confucianism is institutionalized

-

Walled cities as symbols of imperial power

-

Local control through an imperial magistrate who functioned as mayor, judge,

supervisor of tax collection, and supervisor of the conscription for labor

service and military service

-

crop rotation

-

paper making

-

production of porcelain

-

production of lacquer

-

building ships with watertight compartments, multiple masts, and sternpost

rudders

-

water-powered mills

-

magnetic compass

-

wheelbarrow

-

horse collar and breast strap

Regional Rulers: Marquis

Li Cang (d. 186 B.C.E.) and his wife, Lady Dai (d. after 168

B.C.)

In 1972 a sensational discovery of a tomb was made in Changsha, Hunan

province. It was the tomb of Lady Dai. Her corpse was found perfectly preserved

in a set of four interlocking coffins and twenty layers of shrouds. A house

for the afterlife her tomb contained any luxury articles considered desirable

in life – from embroidered colorful silk gowns to 154 lacquer dishes, 51 ceramics,

48 bamboo suitcases of clothing and household goods, baskets of gold pieces

and bronze coins.

Lady Dai was also given an inventory that listed all objects as well as

the food and beverages provided for her. Rice, wheat, barley, millet, soybeans,

red lentils, thirteen different meat dishes made from a variety of seven kinds

of meat.

From the excavation report we learn that Lady

Dai was 1.54 m [5 feet] tall and weighed 34.3 kg [75 lbs].

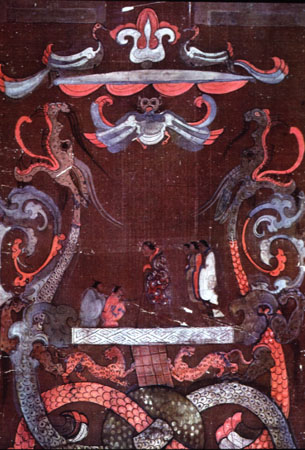

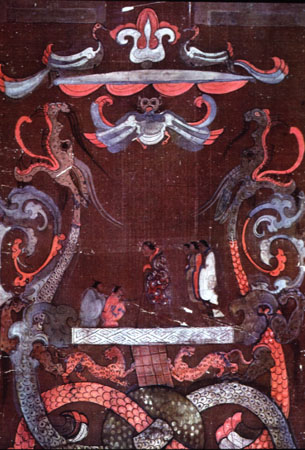

The T-shaped silk banner that covered the coffin of Lady Dai gives

insight into Han ideas about the afterlife.

The

lower section of the banner shows the offerings and ceremonies devoted to

her body soul (po). Sacrificial vessels are provided for her and attendants

are standing next to her, ready to serve her soul which resides in the tomb.

Beneath the tomb we get a glimpse of the creatures living in the underworld:

A deity of the earth carries the foundation of the tomb, her netherworld dwelling.

The

central part of the banner shows Lady Dai in a standing position. She leans

on a cane, while two persons crouch or kneel in front of her and three women,

presumably female attendants, stand behind her.

The upper part of the banner is said to

show the realm of the immortals. The entrance is guarded by two deities holding

the records of the life span of Lady Dai. They

are identified as deities of destiny.

In the top section we can see a standing

woman. She is surrounded by a creature with a snake-like body and flanked

by the depictions of the moon with a toad and a rabbit (which is said to pound

the elixir of immortality) and the sun with a raven. Five birds seem to keep

her company which may represent the figures of the lower parts of the banner.

The

scenes are interpreted as showing the modes of existence of the soul after

death.

The

corpse is placed in the tomb where it is served by underworld attendants.

The body soul enjoys and consumes the burial objects and offerings.

At

the same time the spirit soul (hun)

ascends to the realm of the immortals and seems to rejuvenate during this

process.

The

tomb of Lady Dai's son, who died in the same year, contained more revealing

material. While alive he most likely served as a military official and therefore

was given three maps. One of them shows the area of the tomb, another one

shows the area between the territory of the King of Changsha and the territory

of the people of the Southern Yue. The Southern Yue had been attacked by the

Han in 181 B.C.E. when the Han successfully attempted to expand their territory

to the south and southwest.

In

addition to the maps text manuscripts were found in the tomb. A copy of the

Yijing, a copy of the Daodejing in two halves, texts on law,

fortune-telling, as well as writings on sexual techniques accompanied Lady

Dai's son to the underworld.

The

text on law is of particular interest because it describes obligations of

the ruler: Punishments have to be balanced with rewards, the ruler may not

indulge in consumption, and wars may only be started for a just cause.

The

expansion of the Han Empire under Han Wudi (141-87 B.C.E.)

Under

the reign of Emperor Wu the empire reached a vast territorial extension which

would only be surpassed by the Manchurian Qing dynasty. The first campaigns

were directed to the southwest: The territory of modern North Vietnam was

brought under Han control. Then campaigns led the armies to the northwest

and southern Manchuria as well as northern Korea were subjugated (108-109

C.E.). Yet the control was not permanent: When the Han collapsed both territories

became independent, though Korea remained in close contact with China through

tributary missions.

International

trade via the silk route began to establish, silk being one of the most important

goods that was traded. Han settlements of soldier-peasants were installed

along the border to prevent raids of caravans by non-Chinese neighboring peoples.

Grapes and alfalfa sprouts found their way to China through Zhang Qian, a

general who had been sent out to establish friendly ties with nomads against

the powerful Turk Xiongnu. He was captured and held as a prisoner until he

successfully escaped after 10 years.

Although

trade connected the empires of Rome and Han China, a direct exchange could

not be established. All trade was conducted through Parthian middlemen.

The

Han state was based on Confucian and Legalist principles: Households had to

pay taxes, provide workers for the corvée service, and soldiers for

the army. The officials were recruited from the Confucian scholars who had

to study the Five Classics and were tested before they were appointed to an

office.

Like

the Zhou, the Han began to suffer from internal instability about 200 years

after their dynasty was first established . They moved their capital further

west, to the former Zhou capital Luoyang and managed to retain power until

220 C.E.

During

the Han urbanization of local administrative centers developed: The centers

were walled cities with city gates and housed the seat of institutions of

the bureaucracy. Markets in the cities were supervised by the government,

which included the control of prices.

Major

technological achievements were the invention of the water-powered mill, the

wheelbarrow, the watertight compartment in ships, the sternpost rudder, and

the magnetc compass. Intellctual monuments were the historiographical writings

by the Grand Historian Sima Qian (d. 68 B.C.E.), and the historians Ban Gu

(d. 92 C.E.) and his sister, Ban Zhao. Ban Zhao completed the History of the

Han Dynasty, which had been begun by her brother, and wrote her own book which

served for the education of women in a Confucian mode for centuries and was

titled The Seven Feminine Virtues.