Hist 487/587_2: The Song and Yuan Dynasties

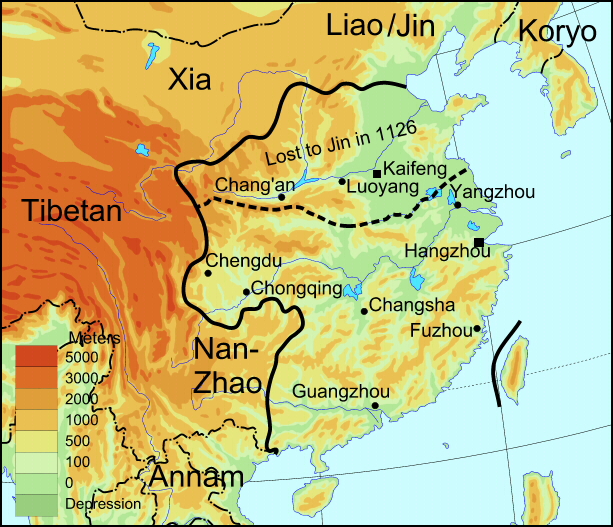

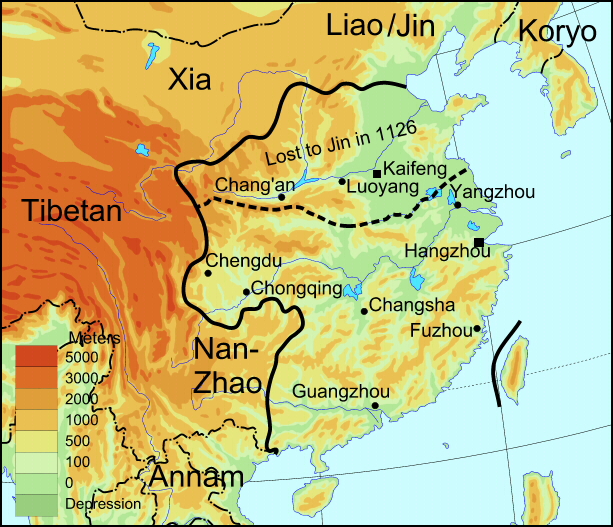

Map of Song China: The dividing line marks the border

between the Jin

and the Southern Song

The first emperor of the Song, Zhao Kuangyin (= Emperor Taizu, r. 960-976) restructured

the administration: The dominance of military officials was replaced by civil

officials who controlled the military. This strategy stopped warlordism and

secured the position of the emperor. Nevertheless the army was needed to defend

the northern borders against invaders and by the 11th century consumed 3/4 of

the financial budget of the Song state.

The Central Government and the Rise of the Scholar Officials

Under the second emperor of the Song, Taizong (r.976-997) power was consolidated through measures of centralization of government institutions. The role of the chancellor(s) (prime minister/s) grew significantly in importance. By the end of the Song, the position of the prime minister was politically almost as important as the role of the emperor. In the ritual context the position of the emperor was never challenged though! [This development became most evident during the yuanfeng era (1078-1085) when Wang Anshi and Sima Guang and their respective supporters fought about the correct measures for reform.]

The State Council consisted of 5 to 9 council members and two chancellors (who also headed the Central Secretariat) and was chaired by the emperor. Associated with the Council of State was the Court of Academicians. Some of its members occasionally served as councilors in investigations.

Three service institutions were responsible for listening

to or dealing with complaints filed by officials or private citizens. They were

independent from each other and all members enjoyed immunity. Therefore none

of the complaints brought to discussion could be associated with any of the

members, who could not be held responsible for the topics and objectives of

the complaints. This granted a certain level of objectivity in the process of

finding a conclusion to a problem. In addition, complaints did not have to take

the ‘officials route’ from the lower ranking of bureaucracy to the

next higher level and so on but could reach the authorities directly and even

get to the emperor’s eyes.

The last decision on any of the discussed matters was the emperor’s vote.

The central government consisted of three large administrative

units subordinate to the State Council:

1. the Three Departments [of the Commission of Finances]:

a. the Department of the State Monopolies [of Salt and Iron]; also controlled water transport; trade

b. the Budget Service, which managed the state budget

c. the Department of Population, which managed the

population registration (registering name, age, address,

and occupation to plan tax revenues, labor service

obligations, military service etc.)

2. the Court of the Army and the Secret Service (which had existed in the Tang but became more important during the Song)

3. the Central Secretariat which was responsible for the administration of personnel (civil service recruitment competitions, appointments, promotions) and justice; it was staffed by civil and military officials

The provincial government which was headed by a governor

who could not hail from the respective province, administered smaller units:

1. Prefectures with important cities (fu; ca. 13) and prefectures designed

for military (jun; ca. 46) or industrial (jian; ca. 4) functions);

2. District (zhou; ca. 255) and subordinate

districts (=circuits; xian)

Every province had four commissioners for the following tasks:

- finances,

- justice (who also was active in supporting agricultural production),

- economy and transportation (who cared for the transport and storage of goods

and managed the goods monopolized by the state, such as tea, salt, and alcohol,

and supervised the casting of coins),

- military affairs

The Song administration was particularly strong in

- the many services that were related to economic questions due to the dominance

of industrial or commercial revenues in the Song economy

- the efficiency of recruitment and promotion of civil servants

During the chancellorship of the reformer Wang Anshi

the Three Departments [of the Commission of Finances] were re-structured.

The Commission of Finances was transformed into a Ministry for State Affairs

and was the leading institution of all six ministeries:

a. Minstery of Personnel [promotions, demotions, examinations of officials]

b. Ministry of Finances [taxes, monopolies, measures and weights]

c. Ministery of Rites [state sacrifices, imperial rituals, ceremonies, tributary

envoys]

d. Ministry of War [weapons and arsenals]

e. Ministry of Justice

f. Ministry of Public Works [Construction of palaces, bridges, streets, irrigation

channels, ships, carts, machines; imperial workshops for manufacturing jewelry,arts

and crafts, chariots etc. for weddings and funerals, ceremonial robes; water

supply control]

The state examinations

In the Song the selection for candidates for the state

examinations reached great perfection. The system originally had been created

to cut the power of the military aristocracy that survived from the Tang (though

the origins of the sytem date back to the Sui emperor Yangdi (r. 605-617 ) who

staged the first selective exams in 606). The prefectures sent in their candidates

after they had passed the prefectural examor they were sent from the schools

in the capital.

Exam topics were:

- Knowledge of the Classics

- Law

- History of writing (epigraphy)

- Mathematics

- Military skills (like shooting from a galloping horse or on the ground; physical

strength)

The most prestigious exams were those testing general knowledge and literary

qualities, like the ability to compose poetry.

In the Song the system became more sophisticated than

ever before:

The basic level was the prefecture exam, followed by the provincial exam. The

next level, the capital exam was supervised by the Imperial Secretariat. Some

selected candidates were invited to the palace exams which were held in the

presence of the emperor.

To ensure objectivity in grading the compositions written by the candidates

were copied and given a number. The officials who graded the texts should not

be able to recognize the author of the text. After the grading was completed,

numbers and names were compared by different officials and a list of successful

candidates was posted at the examination hall. All successful candidates were

now possible candidates for an appointment to office although not all of them

immediately were called to a position.

The advantage of the system is obvious: Imperial relatives, empresses and their

clans, eunuchs who were influential at court etc. could not exert any influence

in political procedures (as they had done successfully in previous dynasties)

but had to leave all political decisions to the officials.

Nevertheless the world of the officials was not without

contradictions. During the Song a certain dynamic of power play among officials’

cliques developed which could hardly be controlled by the emperor as the only

superior authority.

As time went by, Song officials of higher ranks often mistrusted their lower

ranking colleagues because they could easily fall for the temptation to abuse

local power. On the lower ranks officials’ salaries were not paid in money

but in tax revenues. Every official was given land – the size depended

on his rank- that had to be worked by local peasants. In addition he was given

a certain amount of bolts of silk (‘tax silk’). But he was also

allowed to deduct a certain amount from the taxes he had to collect for the

central government from the local population in his administrative unit. This

privilege was increasingly abused in Chinese history. There are many reports

about enraged and desperate people who faced increased taxes or labor services

because their local official had abuse his power. Incidents like these were

only checked by a higher authority if reports were filed.

Power play also existed in the higher ranks of the bureaucracy: Factions and

parties formed who tried to dominate political decisions according to their

own plans. At times there were harsh fights that could result in displacement

of not only an individual official but could ruin hundreds of followers of a

certain political faction and lead to their replacement throughout the provinces

if one’s association with such a group became known. Replacement, displacement,

or a ban to far distant areas included the punishment of the family and all

associates of the culprit.