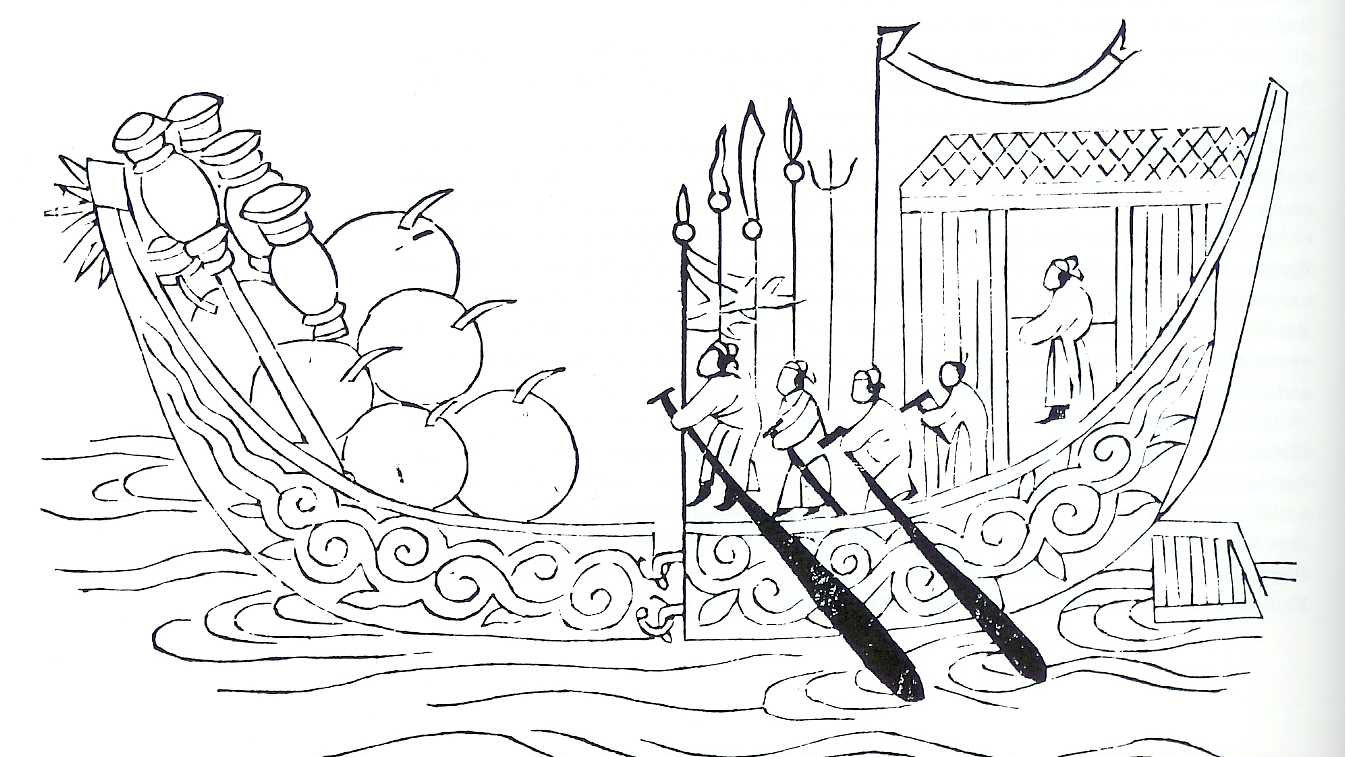

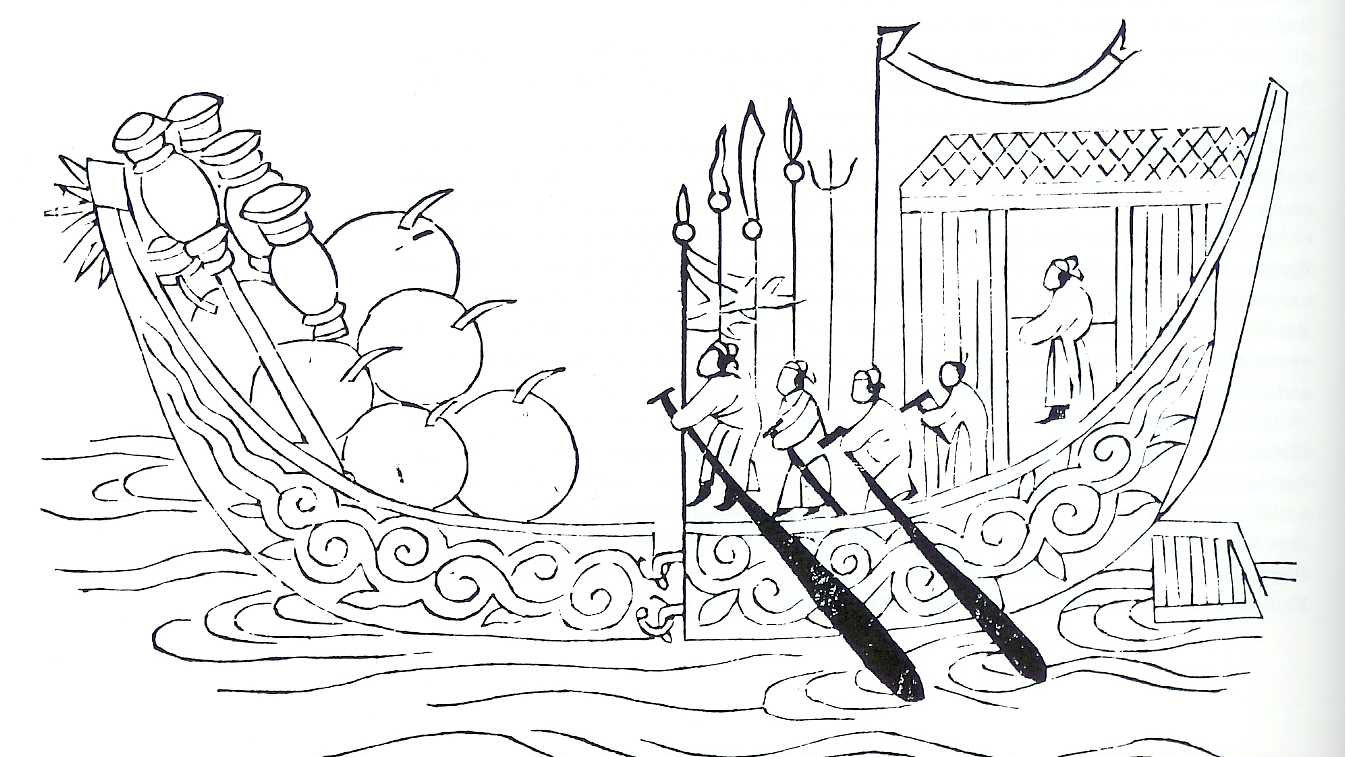

Warship with water mines

Hist 487_3 The Political and Social Elite

The political and social elite of Song China was considerably more uniform than the lower strata of society whose members celebrated the diversity of local customs. In addition, non-Chinese minorities continued to resist the attempts of sinification and transmitted their own cultures to their descendants.

The class of the merchants, frowned upon for centuries because of their lowly regarded position within Confucian society (which was divided into 4 classes: the scholar officials, the farmers, the artisans, and on the lowest level the merchants), became more important than ever before. The dichotomy between capital and labor came to be identified as the contradictory positions of owners of property and capital versus underprivileged classes. The ruling elite of officials associated with the merchants, - a development that had started in the Northern Song and became a non-neglectable factor in the Southern Song. Population growth was matched by commercial growth with the support of the state.

The upper classes

Civil officials

Most important among the civil officials were the government officials which

numbered around 18,700 in the mid-eleventh century; about 1/3 of these officials

were military officials, more than 1,000 were members of the central administration.

They were organized in nine ranks with a differentiation in classification for

each rank (ranks 1a/ 1b to 9a/9b). The b-ranks were somewhat lower in competence

and emolument than the a-ranks. All officials served the government until the

retirement age of 68. Sometimes a pension-like payment was granted, but in general

it was expected that the officials supported themselves by savings and most

important - were supported by their offspring.

In addition to the recruitment of officials via the state examinations there was also a system of recommendations which in some periods easily became abused and led to nepotism. Titles and offices could be sold- a possibility used by merchant families to improve their status by linking their wealth to power.

During the Southern Song when inflation struck, officials were at times desperate to make money and invested in merchant activities. Though officially forbidden, no radical control of theses activities was possible. They invested in pawnshops and warehouses for storing costly goods.

Military officials

Antimilitarism was characteristic for Song civil officials. This was

one reason why military officials were not as highly regarded after the collapse

of the Tang dynasty which was related to a military revolt that had led to social

devastation and political decline. Since the highest aspirations of young men

were oriented towards an official position, few men wanted to join the army

which thus recruited its members from mercenaries. The discipline in the army

of the early Song gave way to a non-disciplined pillaging force that was hated

by the population. Nevertheless, the political situation required that the army

was constantly enlarged and expenses at times reached 5/6 of the state budget.

The education of military personnel consisted in archery, use of the crossbow, fighting with the sword, wrestling, and boxing. The equipment comprised catapults of different sizes for hurling, stones, smolten metal, bombs, and poisened bullets. War junks carried explosive bombs that exploded upon contact with ships of the enemy.

Warship with water mines

The aristocracy and the emperor

Kinsmen of the emperor and relatives of the empress and concubines

belonged to the aristocracy and were bestowed with land and titles by the emperor.

They could be influential in the decision process at court by attempting to

confer favors upon clan members. Eunuchs gained influence at court when associating

with favored concubines of the imperial harem.

The emperor stood between the officials and the court members and often had to mediate between interests of both groups. While politically an active member of decision making his function in the Southern Song had become largely ceremonial.

The merchants

State controlled trade like the transport of supplies to the border

in exchange for salt-certificates, trade on the river-and canal-system in the

south as well as maritime trade, trade in luxury goods, and supplying the city

population with goods for consumption from other parts of the realm were activities

especially supportive for the economy. Barter trade had been replaced by trade

for cash, = strings of coins. Later paper money was issued in the form of promissory

notes. International trade was conducted via the large ports on the southeastern

coast: Chinese junks equipped with watertight compartments sailed to Japan,

Champa, Malaya, South Bengal, and the African coast. Star maps were elaborate

and the compass supported accurate navigation even when the sun and stars were

invisible due to bad weather conditions. Exported goods were silks, brocades,

porcelain (Seladon), ceramics, as well as raw products such as silver, lead,

tin, and copper cash. Favored imports were rhinoceros horn (from Bengal), ivory

(from India and Africa), coral, agate, pearls, crystal, rare wood like sandalwood,

incense, camphor, cardamom and other spices and dyes.

Song dish

Song dish

Rudder of a Chinese Djunk

Rudder of a Chinese Djunk

Song paper money

Song paper money

Guilds

Merchants and artisans were organized in guilds according to trade goods and

professions. The guilds not only supported their members in trade and professional

activities but also provide help and assistance in times of personal need. In

addition the merchants engaged in charitable activities and often supported

officials in their food drives in times of famine or desaster. These acts of

compassion gained them respect and acknowlegement from all levels of society:

Those in need who could be saved and those who noted that the merchants were

not as greedy as often denounced. A symbiosis between local officials and wealthy

merchants was thus often of considerable help for both groups.