Hist 487_9: Literati Culture: Painting and Calligraphy

Alfreda Murck argues that roughly until the 11th century painting had predominantly descriptive and decorative function. Capturing memories and illustrating -historical- events were the prominent objectives of painting.

After the 11th century painting came to be utilized as a possibility to express political consent or dissent. One of the paintings interpreted as an artistic expression for political consent is the hanging scroll 'Early Spring' by Guo Xi (ca. 1010-ca.1090).

Early Spring

Early Spring -details

According to Murck, 'Early Spring' when related to the context of the New Laws issued by the reformer Wang Anshi can be interpreted as a metaphor for the success of the New Laws (New Policies). It seems to document a dynamic, harmonious society in an ideal socio-political hierarchy. The atmosphere of harmony could make it also a positive auspicious image of the New Year, mirroring the dawn of a new era initiated by the reforms. Linked to the aesthetics of a Daoist interpretation of nature it can be seen as a 'vision of the world emerging from the yin of winter', unveiling the success evolution of changes in society as envisioned by Emperor Shenzong and Wang Anshi.

Zheng Xia (1041-1119) who opposed the policies started by Emperor Shenzong and Chancellor Wang Anshi expressed his critique of the increased burdens for the peasants due to loans with high interest payments and the exploitation of merchants who had to pay surcharges on tax exemption fees by painting refugees and government officials who brutalized merchants. His painting is not extant but the records state that he was banished to the mountains in Fujian and later to Yingzhou in Guangdong Province. Zhou Jichang's painting showing the 'upright gentleman' and 'heterodox crooked petty men' resulted in his banishment as well. His rehabilitation was delayed until his case was reviewed after Emperor Shenzong's death.

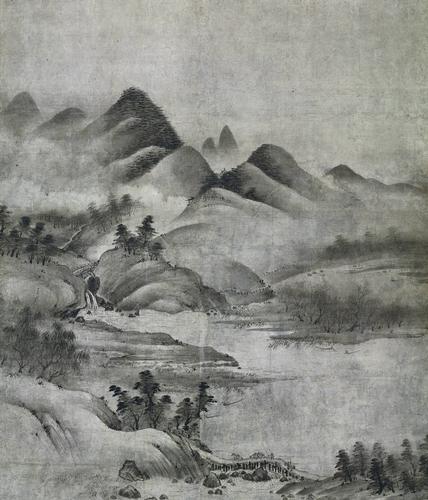

For more than a decade, from the 1070's to the 1080's, political factions were so polarized over the political decisions that would lead to a successful re-ordering of the economy and the state budget (especially with regard to expenses for the military) that an open discussion between political opponents became impossible and even dangerous for the respective party that was not in power. Painting was a possibility to conceal what needed to be revealed. Murck uses the 'Eight Views of [the area of the ] Xiao [and] Xiang [Rivers]' by the painter Song Di (ca. 1015-ca.1080) as a further example for expressing dissent. Song Di and his two brothers were good friends of the conservative politicians Sima Guang (the major opponent of Wang Anshi) and Su Shi. Song Di had been dismissed from office because he was made responsible for a hazardous fire which he could not possibly have helped preventing or stopping because at the time he had already relocated to a different assignment. The irrationality of the dismissal inspired him and others who had been (or felt) mistreated to create paintings that may be interpreted as expressions by 'loyal men who had been wronged'.

[The topic of 'Eight Views of Xiao Xiang'[Rivers in Huanan Province] became very popular in Japan in the 15th and 16th centuries.

Saomi: Eight Views of Xiao Xiang (128,5 cm x 111,7 cm)

During the Southern Song it were the small scale fan paintings and album leaves that became a representative art form. The artistic center where this new format came to be celebrated, was the capital Hangzhou, at the time named Lin'an = Approaching Peace. Ca. 1,000 paintings in the new formats of the period are still extant. Fan paintings became popular gifts that were exchanged at banquets and during ceremonies. The images were complemented by poetry which created a new relationship between image and text, painting and calligraphy on one medium. Poetic inscriptions gracing fan paintings are an aesthetic counterweight to the painting itself and enhance the message communicated by the depiction.

The Imperial court engaged in the production of art when bestowing especially commissioned paintings (portraits of celebrated religious teachers for instance) and calligraphies (from the imperial brush) as gifts: to Daoist and Buddhist temples when their priests had been consulted and asked for spiritual support in times of desaster (natural calamities like flooding, locust plagues, or droughts) and when commissioning didactic programs to promote tradition.

The interactions between the emperor and respected religious masters were expressions of the attempt to combine the teachings of Buddhism, Daoism, and Confucianism: Buddhism was employed 'to cultivate one's mind', Daoism was supposed 'to nurture one's body', and Confucianism was the basis of ruling the world.

Painters at court were appointed and had to produce under the court's direction: Themes comnprise the imperial palace, seasonal festivities, eligious scenes, and representations of nature which usually conveyed several layers of symbolic meaning (i.e. auspicious signs or Confucian principles - indicating wishes for prosperity and good health or political stability and a peaceful rule respectively.) religious topics depicted in the expressive style associated with Chan (=Zen) Buddhism became prominent. Counterpositioning empty space and imagery with sparingly few brushstrokes became an influential aesthetic mode of expression shared by patrons and artists. Excerpts of landscapes sufficed to convey emotions; instead of presenting a 'complete' landscape a selection of few elements was used to inspire the imagination of the viewer. ("One-corner-painting").

During the reign of Emperor Lizong (r. 1224-1264)

Examples of calligraphies and paintings on fans:

Emperor Lizong (1205-1264;

24,5 x 23,5 cm)

Emperor Lizong (1205-1264;

24,5 x 23,5 cm)

Quatrain on Late Spring

How spring makes me sad!

Timidly I bear the passing of spring.

The young lady has no feeling for me,

she treats my love merely as that of a waning spring.

Liang Kai (act. 13th cent.): Poet Strolling by a Marshy Bank (22,0 x

24,3 cm)

Ma Yuan (ca. 1190-

after 1225; professional academy painter of the Southern Song)

Ma Yuan (ca. 1190-

after 1225; professional academy painter of the Southern Song)

Ma Yuan; example of a 'one-corner-painting'

Li Song (act. 1190-1230)

Li Song (act. 1190-1230)

Skeleton Fantasy Game

Li Song

Li Song

Knicknack Peddler

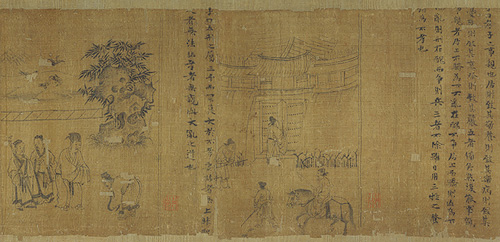

Li Gonglin (ca. 1041-1106): The illustrated Classic of Filial Piety