Ming3 summing up SPRING

The

state-run economy

Population

registration

In the beginning of the Ming the population was successfully registered according to professions. Since occupations were inheritable, the registers were comparatively stable in the first decades of the dynasty. Registers were also created for land and landownership. But several factors turned the registers which were reviewed only every ten years: When natural disasters struck people ran away to escape famine caused by floods, draughts, and locusts. Registration of migrants was only attempted in the Jiajing reign period (1522-1566). Women were often not registered at home because they eventually would marry into a new family yet remain registered with their natal family who had to pay taxes as is she was still living at home and working to contribute her share of the taxes. Changes in profession which became prominent when surplus production provide additional income remained unnoticed. Changes in location equally distorted the registers. Merchants, who were registered in their hometown in the countryside but had moved into the city, paid taxes in their village. Citizens paid higher taxes. This situation was a great advantage for the merchants but created tensions because people who did not own land or had not previously lived in the countryside saw the profits taken by the merchants.

Labor

division between genders

The ideal of labor division between genders that complemented the ideal of the four-class society invoked by Emperor Hongwu at the beginning of the Ming, was summarized in the expression “men plough, women weave”. Manuals by scholars described the necessary works demanded from men in agriculture and the diligence required from women by sericulture and the production of textiles that they produced at home. Ideally men and women both contributed to the tax payments of their household. The topic of men ploughing and women weaving became a stereotype that was applied in literature as well as the arts. The ideology of a peaceful society based on the complementary work accomplished in the rural household was dispersed among the peasants as well as the in the chambers of the court ladies. Handscrolls titled “Pictures of Ploughing and Weaving” showed even palace ladies engaging in the works of sericulture.

The reality looked different in WINTER and SPRING: women and children in the countryside had to help working in the fields. At the same time by the mid-Ming, men were found in an occupation formerly supposedly limited to women. A multitude of woodblock illustrations in manuals shows male weavers at work. When surplus production increased consumption, a change of job could be a lucrative decision:

There was a growing need of artisans in textile production and the industries related to book production such as woodblock carving, the production of paper and ink, the porcelain industry, as well as in the production of metal works and in mining. Therefore many peasants became hired workers and artisans. Francesca Bray has argued that with the increasing production of textiles in workshops by male weavers the role of women in textile production beyond the needs of the family household was reduced to the preparatory works such as ginning and spinning of cotton and reeling of silk. Whether these works alone would have covered the high taxes that were collected in the Jiangnan area is difficult to assess because population registers of the Ming are highly unreliable.

Price

control

Price control aimed at maintaining a fair price level. Merchants who were caught creating prices far beyond the officially acceptable level were judged harshly according the standards set in bribery laws. In the beginning of every month a pricelist based on an average of sales had to set up by the officials who controlled market activities. They also checked whether merchants used the officially approved weights and measures. Merchants had to be registered with the merchandise they traded in. The role of the state in commercial activities was limited. Except for the control measure described above, the officials dealt with trade only when settling commercial disputes.

Labor

service

From the beginning of the Ming until 1561 there existed an elaborate system of labor service obligations that commoners hat to comply with. In addition to taxes in kind, paid in grain and tax silk, later also cotton they had to fulfill –usually annual- labor service obligations. The labor service depended on the occupation of the registered male adult (15-60 years of age). It could consist in being conscripted to official building activities (bridges, dams, dykes, roads, palaces etc.), services like controlling and maintaining the canals, granaries, courier and postal stations, etc., or shift work in the imperial workshops on a regular basis (for instance 1-3 months every year). Shift workers of the imperial workshops had to leave their families and live and work for the fixed amount of time in the workshops. The service harmed those conscripted because they lost the income of their business at home during this period. Therefore labor service was eventually transformed into payments in silver so that the administration could hire workers and artisans to do the work.

The

peasant uprising (1448-1449) led by Deng Maoqi

The peasant uprising started when peasants, enraged by the excessive winter gifts (grain and fuel) they were pressed to pay to their landlords in addition to the tax grain they produced, destroyed the registers. The uprising was ended by military intervention, although Deng who held the position of a small ‘watches and tithing’-overseer had claimed loyalty to the emperor. The rebellion had the objective to challenge the local power of the landowners and to make the emperor aware of the exploitation the landowners practiced, without destroying the social order or overthrowing the dynastic rule. It is therefore regarded as the “first peasant war” in Chinese history.

The

stigma against merchants

The traditional class structure of society had four classes:

- the scholar-officials

- the farmers

- the artisans

- the merchants

Emperor Hongwu occasionally mentioned soldiers, Buddhist monks, and Daoist priests in addition to the first 4 classes. During this reign the reality of class differentiation looked slightly different (the farmers were regarded as most important, followed by artisans and soldiers. Least important were the merchants, and necessary but viewed with suspicion were the scholar-officials. In the long term development the transmitted class stratification remained dominant.

Brooks

argues that the officially promoted stigma of merchants in practice did not

exist anymore in the mid-Ming. He supports his argument with the fact that

merchants were entrusted with grain transports between regions on official

order, after the state-sponsored “preparedness storages” fell into disrepair

by the mid-Ming. Emperor Hongwu had demanded that every county had to establish such

a granary in order to prevent famine. Members

of the gentry even justified their relations with merchants in their records.

One author cites the Book of Changes

to question whether the stigmatization was justified: “People gain advantage

from the circulation of commodities”. From a source of antiquity this statement

seemed to accept merchant activities as essential. The author claimed that

merchants should be taxed lightly because they carried the burden of the business

risk especially when engaging in far distance transports. In addition there

should be no competition between the state and the people in gaining commercial

advantages. The scholar Gui Youguang (1507-1571) claimed

that the exclusion of merchants from gentry life was unfair. In a biography

that he composed for a relative of a merchant named Wang Hong (1491-1543)

he asked: “Why should merchants be regarded as inferior to gentry?” and “How

do we know that merchants can’t be gentry?” Turning to antiquity he stated:

“The ancients did not differentiate four categories of the people”. Few officials

went as far as Gui in their

outspoken acceptance of this new gentry-yet-merchant

concept but a dissolving border between merchants and gentry members cannot

be denied.

In the mid-Ming the gentry did not only consist of the scholar-officials alone. Other educated members of families of degreeholders were part of the network into which merchants could advance through their means of wealth and through educating their offspring.

Silver

Under the

rule of the first emperor the use of silver as currency was repressed. An

attempt was made to stop all private mining (1438) which turned out to be

little effective although culprits had to face capital punishment. The Yongle

emperor reversed this policy as soon as he began to reign. Silver was mined

wherever possible and accessible in

Silver as a currency gained vital importance when taxes in kind and later corvée (forced labor) obligations were converted into payments in silver (1561). The state also gained silver when merchants paid for salt-certificates. These payments were then used to buy provisions for the soldiers in the border regions.

Sources

of Food and Wealth

While passing the exams and obtaining a position in the official bureaucracy were the most prestigious sources of food and wealth, land was considered the basic source of food and wealth. Those who lost their land tried to work as tenants or to find work as hired workers. Sometimes they became small peddlers or they moved to the cities in the hope to escape from registration and find work. Officials as well as merchants could be landowners in the mid and late Ming.

Income from trade became a source of wealth that was regarded with different levels of prejudice during late imperial times. The government used the salt-monopoly to sell salt-certificates to merchants who in return supplied the border settlements of solders and peasants with goods unavailable in their region. Thus salt-merchants became not only wealthy but eventually also respected members of the gentry. Although they had not been born into the middle or even upper class (some late Ming merchants became prominent patrons of the arts) their status was redefined by their capability to accumulate concrete and abstract status symbols.

International

Trade

International

trade became prominent with the expeditions of Admiral Zheng

He between 1405 and 1433. But soon after the last expedition was concluded

(Zheng He dies during on the return trip) the continuation

was stopped. Records and maps of the expedition were officially destroyed

which made the one surviving travel account an especially valuable source

on the expedition. International trade now was limited to coastal trade and

(illegal) trade with Chinese trade posts in

Public

Culture

Literacy

In the Ming literacy on an average level was higher than during any previous period. There are several indicators for this development:

- the fast development of the book market. In addition to new editions of the Classics with commentaries as study aids for the candidates who prepared for the official examinations and manuals with questions and answers of previous exams, there were cheap editions of novels and theater plays, instruction manuals, books on medicine, music notation, calendars etc.

- For officials and their staff administrative handbooks on ritual and law regulations, and bureaucratic rules were published.

- Whole page book illustrations became popular.

- In order to catch the attention of a large readership, ‘journals’ were published whose pages were divided into up to four different registers containing a text, its illustrations, some commentary, and even advertising for new editions, other books by the same author, the bookseller etc.

- The amount of woodblock carvers increased (while their wages were lowered).

- New fonts of characters of reduced complexity in style were created in order to facilitate speedy carving.

- Registers of landownership, tithing (lijia)- registers, and tax books that had to be sent to the Ministry of Revenue were printed. To keep these registers, the responsible person in the community had to be literate.

- Standardized printed contracts were used widely for buying and selling land as well as in commercial activities. The forms were filled in by the parties or by a hired scribe but had to be signed by the parties. Brook mentions a contract signed by a woman.

- The demand made by Emperor Hongwu at the beginning of his reign to establish community schools for adults in order to improve their ability to read and write may have contributed to the increased literacy, although it is difficult to prove that this demand was fulfilled and community schools prevailed over time. They are scarcely mentioned in local gazetteers. Among other objectives the empeor aimed at a wide distribution of his own book “Grand Pronouncements” in order to spread his ideals of law and order.

- Standardized editions for school textbooks were printed.

- The production of ink and paper

increased.

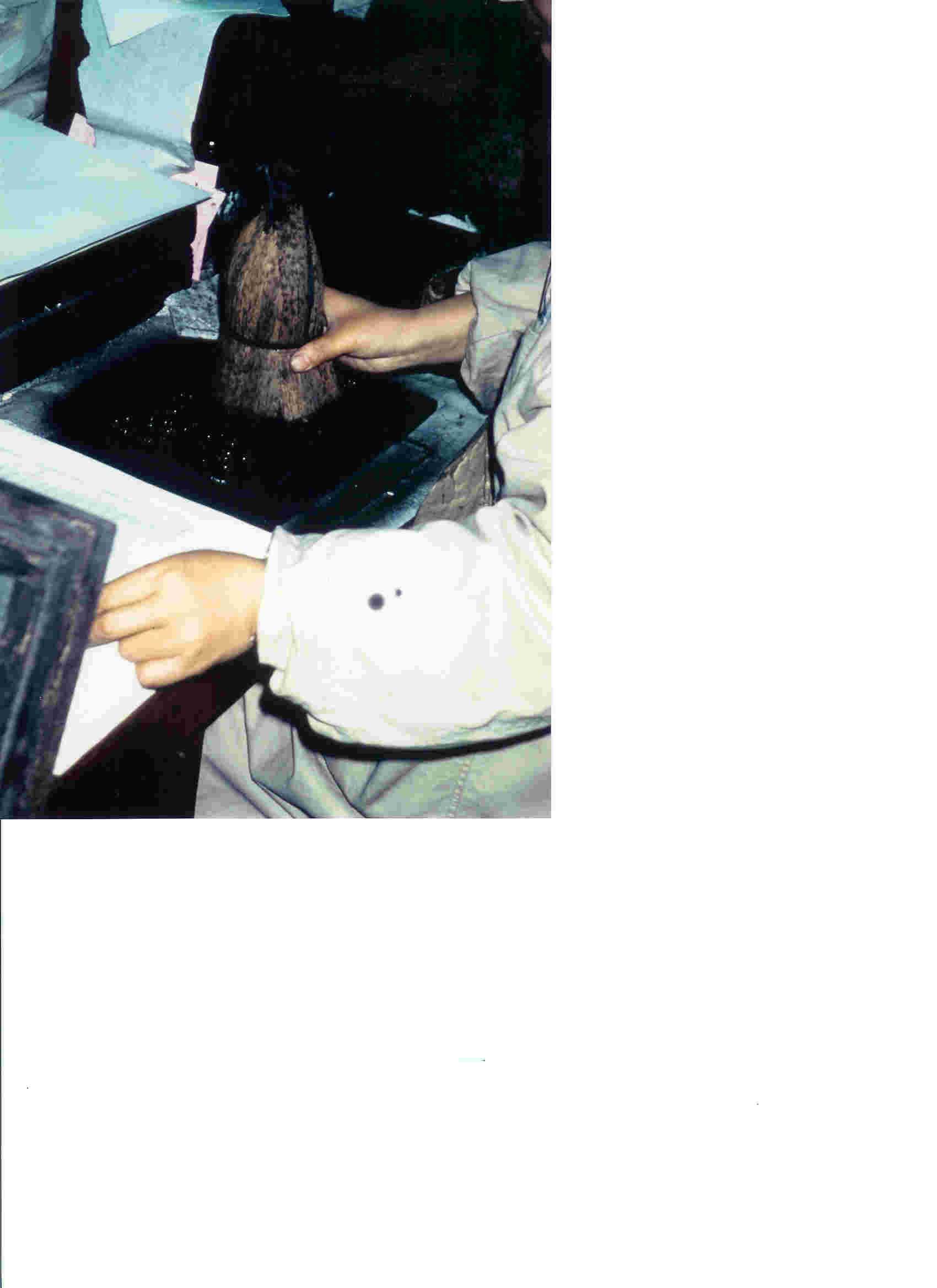

Distributing

ink on a carved woodblock

Distributing

ink on a carved woodblock

" To discriminate nicely between things was at the same time to discriminate sharply among people.” (138)

From the mid-Ming upward mobility was no longer exclusively characterized by the family network one was born into but by the wealth one had accumulated. Consumption of objects and foods defined as desirable and tasteful by the elite of connoisseurs granted social status. Consumption of ‘fashionable things’ included clothing, hats, the size and layout of the house, the interior decoration of the house, and the decoration of the scholars’ studio. It extended to the volumes of books, samples of calligraphy and painting, musical instruments, and antiquities accumulated in the library. Rare plants and exotic trees and rocks in the garden contributed to the status just as much as valuable porcelain in exotic dishes on the table at banquets (Brook quotes the examples of special kind of lichees, longans, pomelos etc.) or the use of a sedan chair for transportation.

Consumption was competitive. The compound cultural and economic value of objects defined status. Although their corruptive character was heavily criticized the wheel could not be turned back. Manuals describing the differences between original objects and imitations became popular literature and achieved what they were supposed to inhibit: The permeability of class borders.