Ming4

Summing up SUMMER

Cont.: Fashionable objects

Clothing

etc.

Sartorial regulations were transgressed

to an extent that social status was not clearly visible any longer in the

streets. Not only was inappropriate dressing common but the volatility of fashion

was created by a constant ‘re-writing’ of the rules of taste to distinguish

between refinement and vulgarity. Rules of taste referred to

► clothes, shoes, hats, ornaments;

► furniture

► food

► works of art (paintings,

antiques) and

► values

and beliefs.

On the concrete level the production of

fakes facilitated to keep up with the latest changes of fashion. On the

abstract level philanthropy was cultivated and ‘goodness calibrated’ by

creating a system that compared moral and monetary values.

Mandarin

robe

Mandarin

robe

Mandarin square

(rank badge) of a civil official

Mandarin square

(rank badge) of a civil official

Altar table

Altar table

Ming cabinet

Ming cabinet

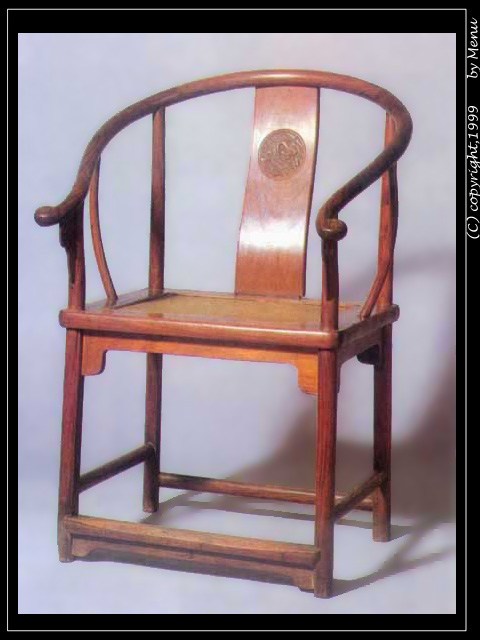

Ming chair

Ming chair

Minf blue-white porcelain

Minf blue-white porcelain

Books

Among the publications that became

fashionable in the mid-Ming were encyclopedias and almanacs that informed a

larger public about sources of officially accepted as well as restricted

knowledge. Fortune telling, erotica, novels etc. became widely available. (See

ming3). Knowledge about the strange inhabitants of foreign countries and their

habits was summarized in the richly illustrated three volume work Assembled Pictures of the Three Realms [i.e.

heaven, earth, and man] (Sancai tuhui).

Brook mentions the manual The Exploitation of the Works of Nature (Tiangong kaiwu) as a

work that although undoubtedly of great practical value disappeared from the

market. This is probably less due to the “unappealing” content as he supposes.

Song Yongxing (1587-1666?) was a highly critical

observer of the Ming - Qing transition and Manchu

politics. His works for this reason may not have been included in the imperial

catalogue Complete Works of the Four

Treasuries (Siku quanshu) of

the Qing Dynasty and therefore found little support

for reprints.

The Jesuit father Matteo

Ricci (1552-1610) describes in detail the technique of Chinese book production.

In return the Chinese official in the secondary capital of

The

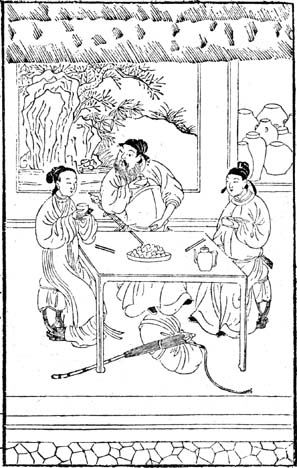

Ming illustration: Gentlemen

in a tavern

Ming illustration: Gentlemen

in a tavern

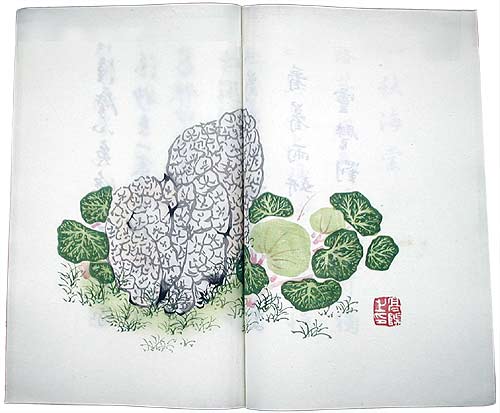

Ming color print

Ming color print

Ming

illustration: Woman practicing embroidery

Ming

illustration: Woman practicing embroidery

Route books and travel

Route books and prospects reveal that

private travel became a favorite past time of the well-to-do. While

►official travel had been a

necessity (to take up a new position or to inspect public works etc.) and were

facilitated by the service stations of the postal network, and

►commercial travel had been common

since the third emperor Yongle lifted the ban on

travel that his father had propagated,

► private

travel became popular only in the late Ming. With local gazetteers and route

books available to prepare travel and maintain orientation on the way “travel

had been absorbed into the gentry project of cultural

refinement” (Brook, 181).

► Women went on pilgrimages,

just like men. This was not always commented on favorably. Orthodox officials

regarded traveling women as rather disturbing, yet temple fairs attracted men

and women alike and the mobility of women increased remarkably.

Production for consumption

Grain and textiles

Grain was the ‘most traded consumption

item’ (Brook, 190) since the preparedness granaries that had been setup under

the rule of Emperor Hongwu were abandoned.

► The graineries were not maintained any longer when grain

transportation was facilitated (by the

► when workers could no longer be

recruited by the lijia

communities which disintegrated due to the changes in the pattern of occupation

that occurred since the early Ming, and

► when

the irrigation system designed for rice paddies was destroyed in those centers

in which paddies were transformed into cotton fields.

The production of grain and textiles

–during the early stage of the dynasty described as ideally accomplished by

labor division among genders (“men plough, women weave”) - could now be found

in regionally different centers of the empire:

Textile production saw extensive labor

division:

►Silk:

1. cultivation of mulberry trees (to feed silkworms with

leaves)

2.

letting the silkworm eggs hatch

3.

feeding the silkworms

4.

tending the silkworms as they stop eating and begin to

spin cocoons

5.

reeling the cocoons

6.

dressing the loom according to the pattern

7.

weaving

__________________________________________________________

8.

sale of fabric

► Cotton:

1.

cultivation of cotton plants

2.

picking cotton

3.

ginning cotton (removing the seed from the cotton ball)

4.

spinning

5.

dressing the loom and weaving

__________________________________________________________

6.

sale of fabric

In the late Ming merchants made the biggest

profits by buying cheap raw material which they distributed among the weavers

and selling the finished product for a high price. The merchants created a

market economy by

► using the state communication

system to link local economies

► organizing regional rural and

urban (workshop) labor into a consecutive production process

► linking production and

consumption

► involving the gentry society (and

thus improving their own social status)

Women in the Commercial Economy

Women were consumers and producers of

goods and services.

► As producers

of commodities they were textile workers in their own households. They produced

not only for the family, but worked for a surplus. Until the end of the Qing

Dynasty they became marginalized in the textile production because the workforce

of male weavers increased with growing diversity of occupations.

►As

producers of services they worked as teachers in the inner chambers, peddlers,

or prostitutes. Brothels were common institutions in Ming cities

visited by male sojourners and migrant workers in the cities who were too poor

to get married. Women could be sold to brothels by fathers or husbands, often they were bought by brothel owners as

orphaned victims after famines.

► In the

late Ming a “cult of romantic love” (often called the 'cult of qing'

=emotion, love) developed in which men searched for educated women as companions.

What made courtesanship attractive for the men who

could afford such a companion was that the relationship was neither based

on a family arrangement (like a marriage) nor was there any dowry transfer

to the family of the woman.

Instead men tried to meet soulmates who were educated on the level of their male

partners and trained in calligraphy, painting, poetry, musical performances,

and were able to participate in sophisticated discussions. Brook mentions that the cult of romantic love

was often used to cover up male “political insignificance and failed careers”.

The romantic loyalty to a lover was equalized to the loyalty to the endangered

and finally fallen dynasty.