Qing1

Costume Portraits of the Qing Emperors Yongzheng and Qianlong

The Qing emperors Kangxi (r. 1661-1722), Yongzheng (r.1723-1735), and Qianlong (r. 1735-1796) were important ruler personalities who not only (re-)shaped the political and social structure of the state during the last dynasty but also had a dominant influence on cultural affairs. All three acted as patrons of the arts and enlarged the imperial collection of cultural treasures.

Emperor Kangxi commissioned handscrolls to be painted which documented his inspection tours to the south.

The Yongzheng emperor is known to have copied Chinese styles of calligraphy, studied Chinese literature extensively, collected art works and compiled catalogues of literary collections.

His son, Qianlong, was even more obsessed with collecting and commissioning works of art than his grandfather and his father. He wrote 42.000 poems (classified by critics as of mediocre quality) and saw himself in line with the [Chinese] Confucian tradition of mastership in poetry and connoisseurship in evaluating pieces of art.

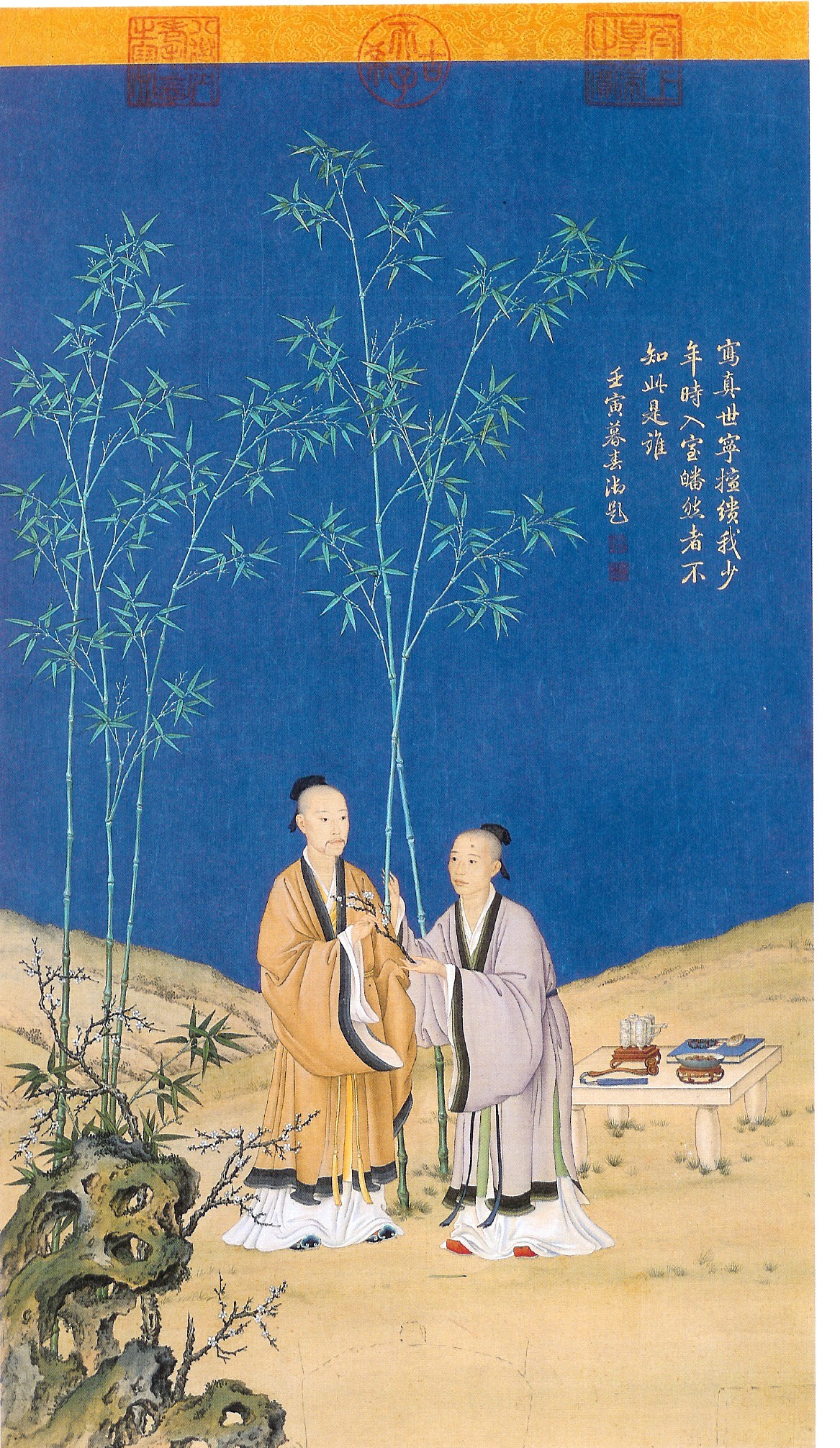

Of all three emperors portraits were painted. But while Kangxi was painted in the traditional formal style sitting in official attire with a stern face looking straight forward at the observer, Yongzheng and Qianlong are presented in a variety of informal or, in the case of Yongzheng, even foreign costumes.

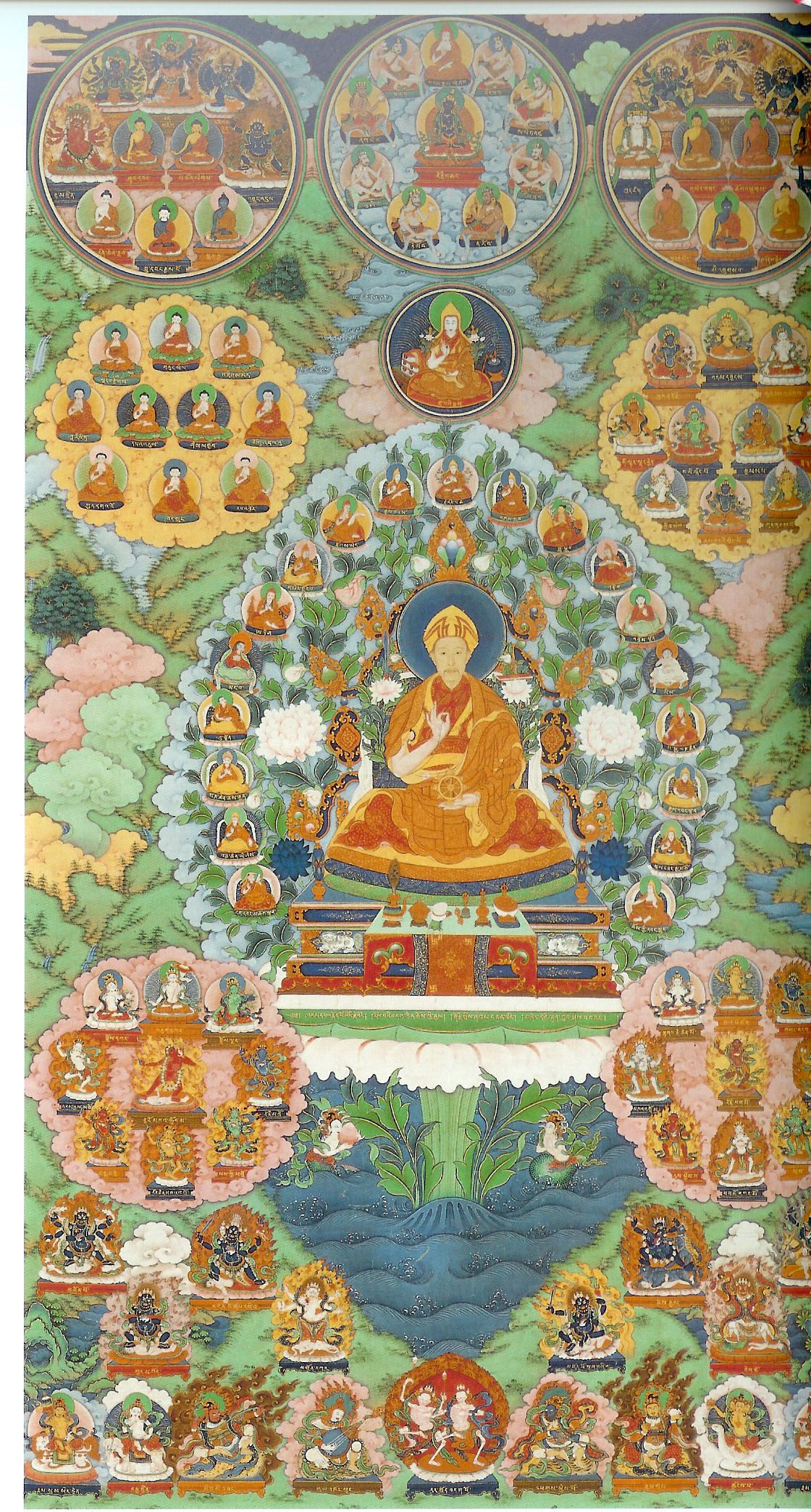

We see Yongzheng as a Persian warrior, a Turkish prince, a Daoist magician, a fisherman, a Tibetan monk, a Mongol nobleman, and as a Chinese scholar observing nature or occupied with playing music or writing calligraphy in a natural setting.

These ‘masquerade

paintings’ followed a trend popular at European courts: masked parties at

the court of Henry VIII (r. 1509-1547) as well at other European courts in

the 17th century when the aristocracy was fascinated with exotic

costumes and habits. While paintings of European masquerade participants showed

the persons without masks in their exotic costumes, the Manchu emperors’ masquerade

paintings have to be seen in a political context. According to the art historian

Wu Hung (

The association

of the name

Portrait of the Qianlong Emperor in front of the White Pagoda

18th cent., spurious seals of Guiseppe Castiglione

Tranquil Spring

Giuseppe Castiglione

For more information and color photographs of the different costume portraits of the emperors see the article by

WU Hung, “Emperor’s Masquerade – ‘Costume Portraits’ of Yongzheng and Qianlong”, Orientations July/August 1995, 25-41. (UO Art Library)