Black hole is cosmic body of extremely intense gravity from which nothing, not even light, can escape. A black hole is formed when matter ungoes extreme pressures, such as the death of a massive star. When such a star has exhausted its internal thermonuclear fuels at the end of its life, it becomes unstable and gravitationally collapses inward upon itself. The crushing weight of constituent matter falling in from all sides compresses the dying star to a point of zero volume and infinite density called the singularity. Details of the structure of a black hole are calculated from Albert Einstein's general theory of relativity. The singularity constitutes the centre of a black hole and is hidden by the object's "surface," the event horizon. Inside the event horizon the escape velocity (i.e., the velocity required for matter to escape from the gravitational field of a cosmic object) exceeds the speed of light, so that not even rays of light can escape into space. The radius of the event horizon is called the Schwarzschild radius, after the German astronomer Karl Schwarzschild, who in 1916 predicted the existence of collapsed stellar bodies that emit no radiation. The size of the Schwarzschild radius is thought to be proportional to the mass of the collapsing star. For a black hole with a mass 10 times as great as that of the Sun, the radius would be 30 km (18.6 miles).

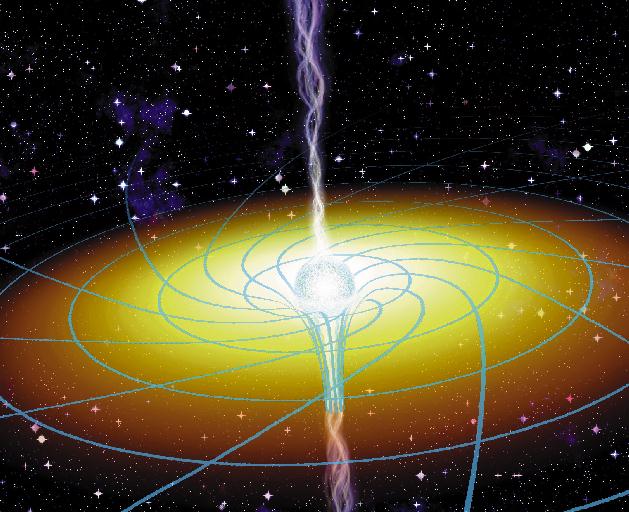

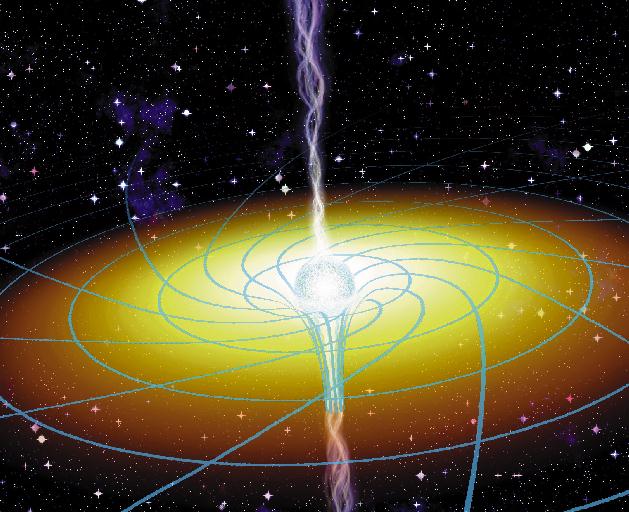

Black holes are difficult to observe on account of both their small size and the fact that they emit no light. They can be "observed," however, by the effects of their enormous gravitational fields on nearby matter. For example, if a black hole is a member of a binary star system, matter flowing into it from its companion becomes intensely heated and then radiates X rays copiously before entering the event horizon of the black hole and disappearing forever. Many investigators believe that one of the component stars of the binary X-ray system Cygnus X-1 is a black hole. Discovered in 1971 in the constellation Cygnus, this binary consists of a blue supergiant and an invisible companion star that revolve about one another in a period of 5.6 days.

Some black holes apparently have nonstellar origins. Various astronomers have speculated that large volumes of interstellar gas collect and collapse into supermassive black holes at the centres of quasars and peculiar galaxies (e.g., galactic systems that appear to be exploding). A mass of gas falling rapidly into a black hole is estimated to give off more than 100 times as much energy as is released by the identical amount of mass through nuclear fusion. Accordingly, the collapse of millions or billions of solar masses of interstellar gas under gravitational force into a large black hole would account for the enormous energy output of quasars and certain galactic systems. In 1994 the Hubble Space Telescope provided conclusive evidence for the existence of a supermassive black hole at the centre of the M87 galaxy. It has a mass equal to two to three billion Suns but is no larger than the solar system. The black hole's existence can be strongly inferred from its energetic effects on an envelope of gas swirling around it at extremely high velocities.

The existence of another kind of nonstellar black hole has been proposed by the British astrophysicist Stephen Hawking. According to Hawking's theory, numerous tiny primordial black holes, possibly with a mass equal to that of an asteroid or less, might have been created during the big bang, a state of extremely high temperatures and density in which the universe is thought to have originated roughly 10 billion years ago. These so-called mini black holes, unlike the more massive variety, lose mass over time and disappear. Subatomic particles such as protons and their antiparticles (i.e., antiprotons) may be created very near a mini black hole. If a proton and an antiproton escape its gravitational attraction, they annihilate each other and in so doing generate energy--energy that they in effect drain from the black hole. If this process is repeated again and again, the black hole evaporates, having lost all of its energy and thereby its mass, since these are equivalent.

Excerpt from the Encyclopedia Britannica without permission.