The spirit of ukiyo-e lives on through contemporary manga

Roots

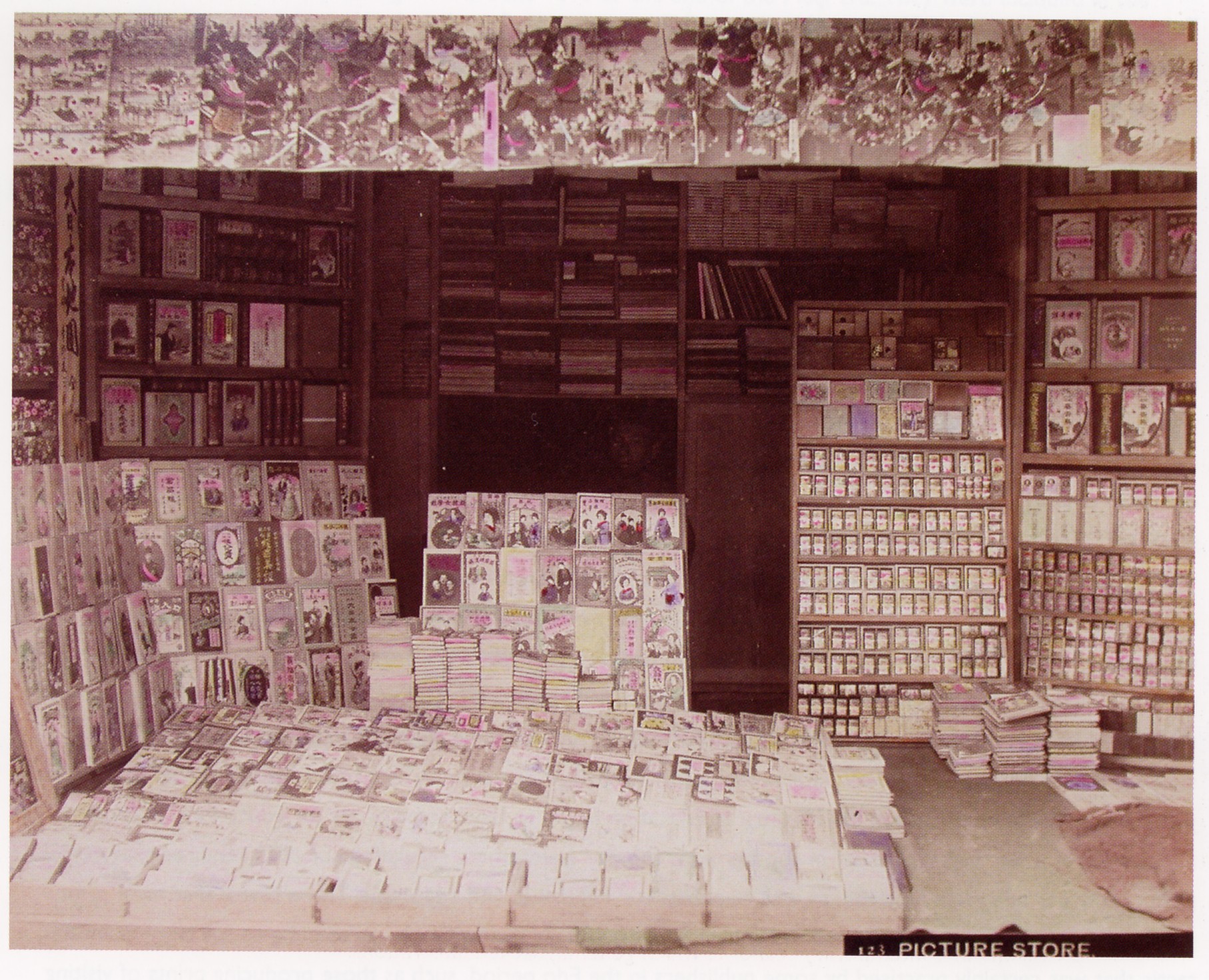

Modern day Japanese manga (comics), fathered by Osamu Tezuka (1928-1989) after World War II, has its roots in both United States and Japanese culture. While on the U.S. side it draws from post-war comic books and the animations of Disney Studios, on the Japanese side it has more ancient roots. Twelfth century emaki (Japanese scrolls), seventeenth century ezoshi (small and inexpensive books of humor or erotica), the Japanese Punch-type satirical comics of the 1860s, and 18th and 19th century ukiyo-e (prints of the floating world), all gave origin to modern day manga.Similarities

Like manga, ukiyo-e were affordable and made for a mass audience. (Print production in Japan during the 1850s is estimated at four to five million sheets annually1 and annual Japanese manga production in the 1980s is estimated at over 1 billion in magazine and book form.) In content, both manga and ukiyo-e employ themes of sex, violence, tales of the rich and famous, the supernatural, and heroes and villains, to feed popular tastes. In form, the simplicity of the use of line and the convention of flat space is favored. Both rely on picture more than text to tell the story and use “a variety of pictorial conventions that are mutually, wordlessly, understood by the artist and reader.”2 Much like ukiyo-e, the domestic recognition of manga as culturally significant, rather than just a low form of entertainment, was prompted by Western acceptance and critical praise.Yoshitoshi Tsukioka (1839-1892)

By the time Yoshitoshi had created the series One Hundred Aspects of the Moon, ukiyo-e was in its last days, losing its mass popularity to the new technologies of photography and lithography. But there was such appeal in the Moon prints that tens of thousands were sold. What stands out about these prints is the supremacy of the images, symbols and emotions conveyed. They are much like modern day manga in relying on visual rather than written narrative.1 This number does not count woodblock printed books which would add substantially to this total.

2 Frederik L. Schodt, Manga! Manga! The World of Japanese Comics, Kodansha International, 3rd edition, 1998. p. 21.