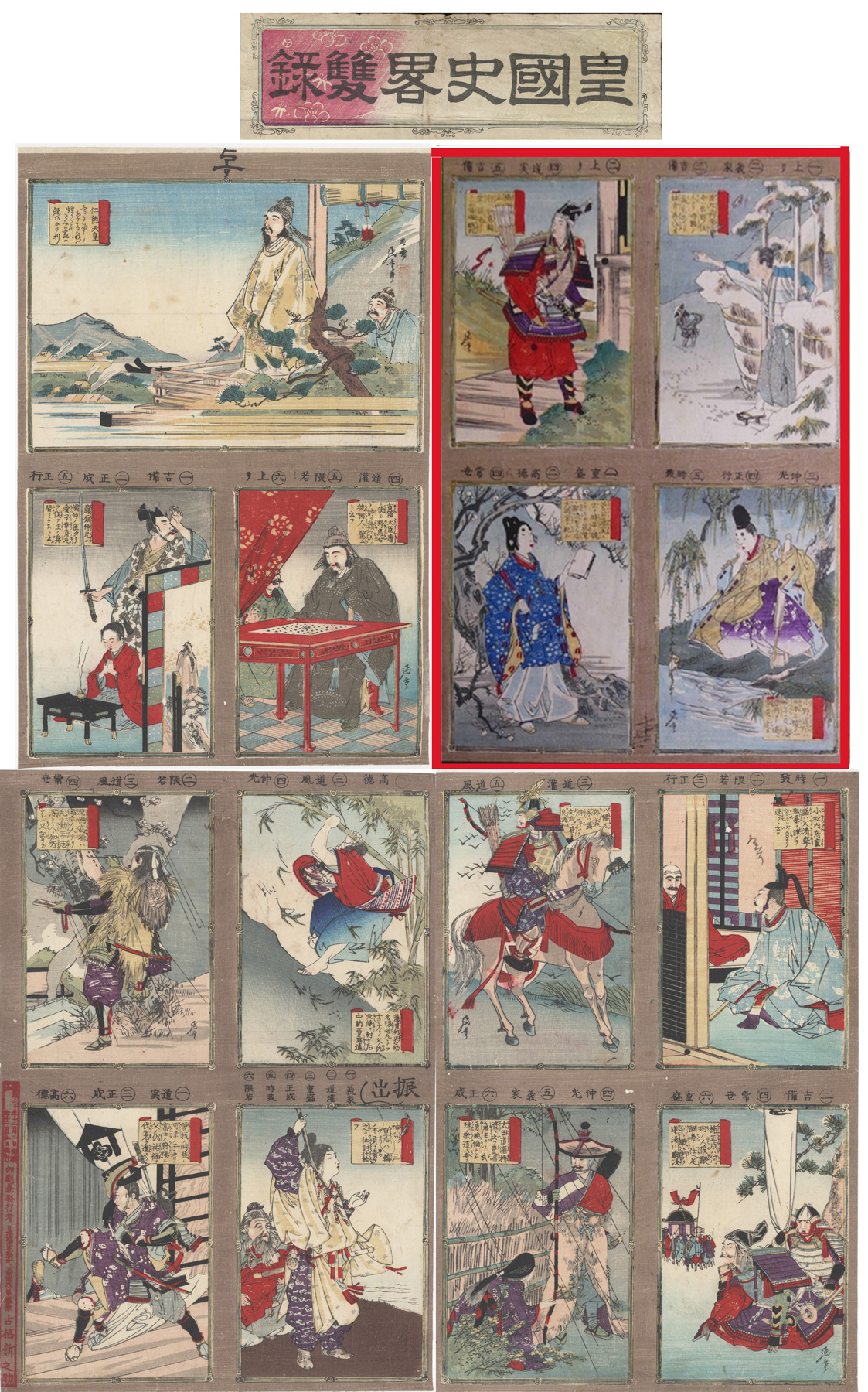

About This PrintThree of four sheets of an e-sugoroku (pictorial board game), each sheet depicting three or four scenes of famous stories demonstrating moral actions to be emulated. Brief explanatory texts appear in the scrolls on each image, beginning with Empress Jinjū (shown in the lower right at the starting point, furidashi, who is said to have reigned from 201 to 269 and finishing at the goal, agari, at the top left, with Emperor Nintoku who is said to have reigned from 313 to 399.

Note that the sheet in the lower left corner, surrounded by a red border, is not part of the collection, but was part of the gameboard as issued. In addition, the title of this e-sugoroku, 皇国史畧雙録 (Kōkoku shiryaku sugoroku, "Brief History of Japan Board Game"), which is not present on any of the three sheets in the collection, is taken from the records of National Library of Australia which holds the complete e-sugoroku in its collection.1

About e-Sugoroku Source: "Playing with Filial Piety – Some Remarks on a 19th-Century Variety of Japanese Pictorial Sugoroku Games," by Susanne Formanek and Sepp Linhart appearing in the magazine Board Game Studies, Volume 5, International Journal for the Study of Board Games, CNWS Publications, 2002.

The earliest surviving examples of e-sugoroku date from the 17th century. Starting as Buddhist teaching tools, by the end of the 17th century had become popular entertainment for the common people. The increasing popularity of e-sukoroku is tied to the development of woodblock printing, with the "game-boards" being composed of multiple standard oban size sheets after the advent of multicolor woodblock print technique towards the end of the 1700s. "Game-boards were often assembled from two, four or nine sheets joined together, so that the sizes of the finished products vary, up to a size of about 90 x 70 cm. They were sold in folded form (rather like modern maps), in envelopes or wrappers into which they could be easily inserted again after use."

In order to play, players needed a die and markers or figures with which to play. All sugoroku games have a starting square usually called furidashi and a goal called agari. In this collection's e-sugoroku, a tobi sugoroku or "jumping sukoroku," each field or square in the game gives instructions as to which square players must proceed to, when a given number is thrown. Sometimes, fewer than 6 numbers are given; in this case, players who fail to come up with one of the stipulated numbers have to wait for the next round in order to make a move.

The Stories Depicted in the Three Sheets in The Collection

Lower Right Sheet (clockwise from the lower right image) Empress Jingū 神后皇后八 [神功皇后] (170-269) On the bottom right in the starting square (with the characters 振出 furidashi above it) we see Empress Jingū (r. 201-269), wife of Emperor Chūai, fishing as her minister Takenouchi no Sukune looks on. This scene takes place after the death of the emperor, who died as he planned to invade the Korean peninsula. "Jingū and Sukune fish for offerings to the gods, and the trout she pulls out of the river in this print is a symbol of good luck, indicating to the empress that she should take over her husband's planned invasion. Legend has it that while Jingū led the invasion, she was able to keep her unborn son contained within her womb for three years to protect him from the dangers of war; when the invasion ended, she finally gave birth to Emperor Ojin. Today, Jingū is venerated as the Shinto goddess of safe delivery."2

Soga (Juro) Tokimune 曾我時致 (1174-1193) One of the great vendetta stories in Japanese folklore, the Soga brothers, Sukenari (Soga Juro Sukenari) and Tokimune (Soga Goro Tokimune), take their revenge on their father's murderer, Kudō Suketsune, at the hunting camp of the shogun Yoritomo on the 18th day of the fifth month of 1193. In this scene, set after Suketsune is killed by the brothers and Juro has also been killed, the hot-blooded Tokimune is grabbed by the wrestler Goromaru. Tokimune is taken before the shogun and later executed. This story is told in The Tale of the Soga Brothers (Soga monogatari 曽我物語) written in the late Kamakura period (1185–1333.)

Kojima Takanori 児島高徳 (1312-1382)

The top left image depicts Kojima Takanori, dressed in peasant garb, writing a poem on a cherry tree to the exiled Emperor Go-Daigo telling him to not lose heart.

The story of Kojima Takanori and Emperor Go Daigo is told in the Taiheiki Monogatari, the Japanese historical epic written in the late 14th century. It recounts how Takanori, a devoted retainer of Emperor Go Daigo (r. 1318-1330), celebrated in Japanese history for the Kenmu Restoration in which the bakufu was overthrown and power restored to the imperial court, came to the aid of the exiled Emperor.

In 1331, Emperor Go-Daigo (1288-1339) was deposed and sent into exile by the Hōjō family. Takanori, a loyal supporter of the Emperor, disguised himself as a peasant and tracked the Emperor to the small inn on the border of Bizen province. As a message to the Emperor, Takanori rips a patch of bark off the cherry tree and writes a classical Chinese poem of loyalty, recounting how the King of Yue was saved by his loyal retainer, Huan Lei. Although the Emperor was heartened by the poem, it was two more years before he was reinstated.

Fujiwara Kunimitsu 藤原仲光 (active c. 1325)

In the upper right we see thirteen year old Fujiwara Kunimitsu escaping after he has avenged the death of his father by using bamboo to form a bridge across the mote surrounding the mansion of the Governor of Sado Island. As the story goes Kunimitsu's father, Fujiwara no Suketomo, Emperor Go-Daigo's chief confidant, was exiled to Sado Island where he was killed on the command of the Kamakura regent, Takatori. Upon hearing of his father's exile, Kunimitsu, despite his mother's tearful remonstrances, set out from Kyoto to bid his father farewell. Although moved by the boy's affection the Governor was fearful of the regent and commissioned Homma Saburo, a member of his family, to kill Suketomo.

"Kunimitsu determined to avenge his father, even at the expense of his own life. During a stormy night, he effected an entry into the governor's mansion, and, penetrating to Saburo's chamber, killed him. The child then turned his weapon against his own bosom. But, reflecting that he had his mother to care for, his sovereign to serve, and his father's will to carry out, he determined to escape if possible. The mansion was surrounded by a deep moat which he could not cross. But a bamboo grew on the margin, and climbing up this, he found that it bent with his weight so as to form a bridge. He reached Kyoto in safety and ultimately attained the high post (chunagon) which his father had held."3

Upper Left Sheet (clockwise from the top image)

Nintoku Tennō 仁徳天皇 (reigned 313-399)

On the top, the "goal" or finish of the game, we see the 16th Emperor of Japan, Nintouko4, looking down upon the villages near his palace as cooking smoke pours from the chimneys of the homes. As the story is told, the Emperor, after moving his capital and palace to Naniwa, comments that his people must be too poor to cook, as he sees no fires coming from their chimneys. After suspending the collection of taxes for three years, Nintoku again surveys his people houses and is pleased to see smoke arising from their chimneys. While not depicted in this scene, it is said that he told the Empress who complained about the poor state of the palace due to the suspension of taxes, "Listen carefully. The business of governing must be based on people. If the people are rich, I am also rich."5

Minister to China Kibi 吉備大臣唐 (Kibi no Asomi Makibi 吉備真備, 695-775)

In the scene on the bottom right we see the Emperor's emissary to China, Kibi no Asomi Makibi, sitting before a table with a Chinese go board on it. As told in the Illustrated Story of Minister Kibi’s Adventures in China, Kibi has returned to China as the emperor’s emissary and has been promptly locked away by Chinese officials who remembered their humiliation during Kibi's first visit as he demonstrated his superior sage knowledge and wit. While the Chinese officials do not want to blatantly murder Kibi, they demand that he prove his abilities by accomplishing various impossible intellectual tasks with the hope that he will starve in captivity. In this print he is seen sitting before a go board, a game he had not played before. Winning the game with the help of the spirit of a previous Japanese emissary who had been killed in China, Kibi also passes other seemingly impossible intellectual tests and is eventually allowed to return to Japan after the Chinese officials attribute an eclipse to Kibi’s doing.

Fujiwara Nakamitsu 藤原仲光 (10th century - middle of Heian Period)

The scene on the bottom left depicts Fujiwara Nakamitsu, chief retainer of the Lord of Settsu, Mitsunaka Minamoto (912?-997), about to cut his own son's head off. As this tragic tale goes, Minamoto's son, Bijomaru, was sent off to a Nakayamadera Temple to receive training to become a priest. However, he was not serious about his training and when his father realized that Bijomaru could not read Buddhist scriptures, nor compose a tanka(a 31-syllable Japanese poem), nor play music, he became furious and ordered his chief vassal, Nakamitsu Fujiwara, to cut off Bijomaru's head. Nakamitsu knew that even though ordered to kill Bijomaru, he could not kill the son of his lord. When Kojumaru, one of Nakamitsu's sons, heard of his father's plight, he told his father to kill him instead. As shown in the print, Nakamitsu found Kojumaru with his hands joined in prayer, eyes closed. Holding back his tears, Nakamitsu slew his son, and let Bijomaru secretly go off to Mount Hiei. When Bijomaru found out what had happened he devoted himself to becoming a priest. After becoming a high-ranking priest, called Genken-sozu, he built Shodoji Temple to enshrine the spirit of Kojumaru.6

Upper Right Sheet (clockwise from the top left image)

Hachimantarō 八幡太郎 (Minamoto no Yoshiie 源義家, 1041-1108)

On the top left we see Hachimantarō, the nickname of the 11th century famed archer Minamoto no Yoshiie, watching the activity of a flock of geese. As the story goes, Yoshiie while leading his his army toward Kanazawa Stockade, in what became the final battle of the Later Three Years War, sees a flock of geese rise from a field of grass and scatter. Surmising that enemy soldiers hiding in the grass have disturbed the geese, he sends men to investigate. More than thirty of the enemy are driven out of the grass and promptly put to death. Yoshiie later reflects that study of Ōe no Masafusa's book on military strategy informed him that "when soldiers conceal themselves in the grasses of plains, they disturb flocks of geese." 7 Yoshiie's followers are impressed and grateful that their lord is so learned in the art of war.

Komatsu Daifu Shigemori 小松内府重盛 (Taira no Shigemori 平重盛, 1138-1179)

In the scene on the upper right we see Komatsu Daifu Shigemori (Taira no Shigemori) in conversation with his father Tairo no Kiyomori, reasoning with him to reconsider his desire for vengeance after a plot is discovered to overthrow him. The story of the rise and fall of the Taira (Heike) clan is told in the mid-13th century chronicle Tale of the Heike.

"Kiyomori’s oldest son Shigemori, was not like his father who was rash, arrogant, and violent. Shigemori was a virtuous and thoughtful man who understood that the deeds of his father would eventually be the undoing of the Heike clan. After a plot against the Heike clan by the cloistered emperor [Go-Shirakawa] and a court noble, Narichika was discovered, Kiyomori had resolved to have Narichika executed for his hand in the plot. Shigemori however, comes to his aid and reminds his father that because all evil deeds are repaid with destruction, he should spare Narichika to spare the Heike clan from destruction in the future. Shigemori tells his father “It is my belief that a man’s good or evil deeds are inherited by his descendants. It is also said that the accumulation of good deeds brings happiness, while sorrow waits at the gate of him who commits evil.” This persuades Kiyomori into sparing Narichika’s life, [who] is exiled and later killed by Kiyomori’s order."8

Kusunoki Masashige 楠正成八河内 (1294-1336) On the bottom right we see the great warrior tactician and paragon of loyalty Kusunoki Masashige kneeling down observing the movement of Ashikaga Takauji, the ruling shogun (Kamakura shogunate), before the Battle of Minatogawa which pitted forces loyal to Emperor Go-Daigo against the shogunate. Kusunoki, a leader of forces loyal to Emperor Go-Daigo, joined the battle knowing of his certain defeat. He committed suicide to avoid capture after his defeat.

"After the Meji Restoration, when a new government was searching for a way to reconcile Japan's samurai past with her Imperial present, Kusunoki Masashige came to the fore. A samurai loyal to the emperor, even to his certain death, was a valuable symbol, and much exploited during the era of Japanese Imperialism. This ended up with ugly connotations, with young men hurling themselves futilely into American ships in World War II by aircraft or fast boat, inspired by the exploits of Masashige."9

Ōta Dōkan 太田道灌持資 (1432-1486) In the bottom left panel is an illustration of an anecdote from the life of Ōta Dōkan, also known as Ōta Sukenaga (太田 資長) or Ōta Dōkan Sukenaga, a Japanese samurai warrior-poet, military tactician and Buddhist monk. Dōkan is best known as the architect and builder of Edo Castle (now the Imperial Palace) in what is today modern Tokyo. In this scene Ōta, caught in a sudden rainstorm while out hunting, stops at a farmhouse and asks the girl who lives there for a raincoat. "The girl returned with a bunch of yellow mountain roses (yamabuki) and a poem which read The mountain roses enrich our house with flowers, yet there is sadness here, for those riches are an illusion, and our flower has no fruit. In the poem she uses the word mi to say fruit referencing the straw raincoat, a mino, that Dōkan had asked for. Dōkan was confused and fumed at her; all he had asked for was to borrow a straw raincoat and she brought him a useless poem and a bundle of flowers? How stupid could this – surprisingly well-educated – peasant girl be? "When he returned to his castle one of his retainers explained the poem to him. He said that the family was too poor to be able to afford straw raincoats to lend to passersby, hence the usage of Prince Kaneakira’s poem and the giving of the yellow mountain flowers as a polite apology. Dōkan realized the error of his ways and decided to devote himself to the study of intellectual things, such as poetry and architecture. "[B]ecause of their meeting Dōkan was able to become a well-mannered, properly educated samurai, who was eventually able to build the foundation for Japan’s capital city.10 1 National Library of Australia Bib ID 7342228 https://catalogue.nla.gov.au/Record/7342228?lookfor=(sugoroku)%20AND%20(nobushige)&offset=2&max=22 website of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art https://collections.lacma.org/node/1913753 A History of the Japanese People: From the Earliest Times to the End of the Meiji Era, F, Brinkley, The Encyclopaedia Britannica Co, 1912, P. 378.4 according to the traditional "order of succession"; website of the City of Kawanishi http://www.city.kawanishi.hyogo.jp/english/7515/legends/temple.html5 website of Japanese Mind Understanding the Japanese culture, mind and traditionhttps://japan246.com/category/original-japanese-style-democracy/6 We Japanese, Volume II, Atsuharu, Sakay, Miyanushita, Hakone, Fujiya Hotel, 1947 edition, p. 144.7 Warriors of Japan as Portrayed in the War Tales, Paul Varley, University of Hawaii Press, 1994, p. 42.8 Rise and Fall of the Heike: An Analysis of The Tale of The Heike, author unknown, published on the website of Michigan State University https://msu.edu/~will2269/Tale%20of%20the%20Heike.docx9 website of the SamuraiArchives https://www.samurai-archives.com/masashige.html10 website of Richard C. Shaffer https://dickjutsu.wordpress.com/2016/01/22/samurai-gaiden-ota-dokan-sukenaga/

Print Details IHL Catalog

| #1708 | | Title or Description | Brief History of Japan Pictorial Gameboard

皇国史畧雙録 Kōkoku shiryaku sugoroku

| | Series | | | Artist | Yōsai Nobushige (active 1894-95)

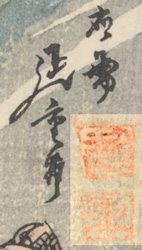

| | Signatures | Each of the three oban-size sheets in the collection contains Nobushige's signature 延重 in two locations on the sheet in the form shown below on the right. On IHL Cat. #1708 which contains the image of Emperor Nintoku, which is the finishing point for the game, Nobushige's signature takes the form of 應需延重画 (ōju Nobushige ga) or "drawn by Nobushige by request," accompanied by two square seals likely reading 延 (nobu) and 重 (shige), as shown below on the left.

signature, top print: 應需延重画 ōju Nobushige ga sealed: 延重 Nobushige | signature, lower right print: 延重 Nobushige |

| | Seal | Nobushige 延重 (see above), on the top image of IHL Cat. #1708 | | Publication Date | December 1897, as shown in the left margin of IHL Cat. #1710

| | Publisher | Furuhashi Shinnosuke for the firm Sin'eidō 古橋新之助 新栄堂 [Marks: pub. ref. 078]

[as printed in the bottom left margin of IHL Cat. #1710] | | Impression | good | | Colors | excellent | | Condition | good - minor soiling, paper imperfections and on print IHL Cat. #1708 a vertical fold through the top image. | | Genre | ukiyo-e; e-sugoroku

| | Miscellaneous | | | Format | vertical oban 4 sheets

| | H x W Paper | IHL Cat. #1708: 13 7/8 x 9 1/8 in. (35.2 x 23.2 cm)

IHL Cat. #1709: 13 9/16 x 9 3/16 in. (34.4 x 23.3 cm)

IHL Cat. #1710: 13 1/2 x 9 1/2 in. (34.3 x 24.1 cm) | Literature

|

| Collections This Print

| National Library of Australia Bib ID 7342228 |

last revision:4/19/2020 |