About This Print

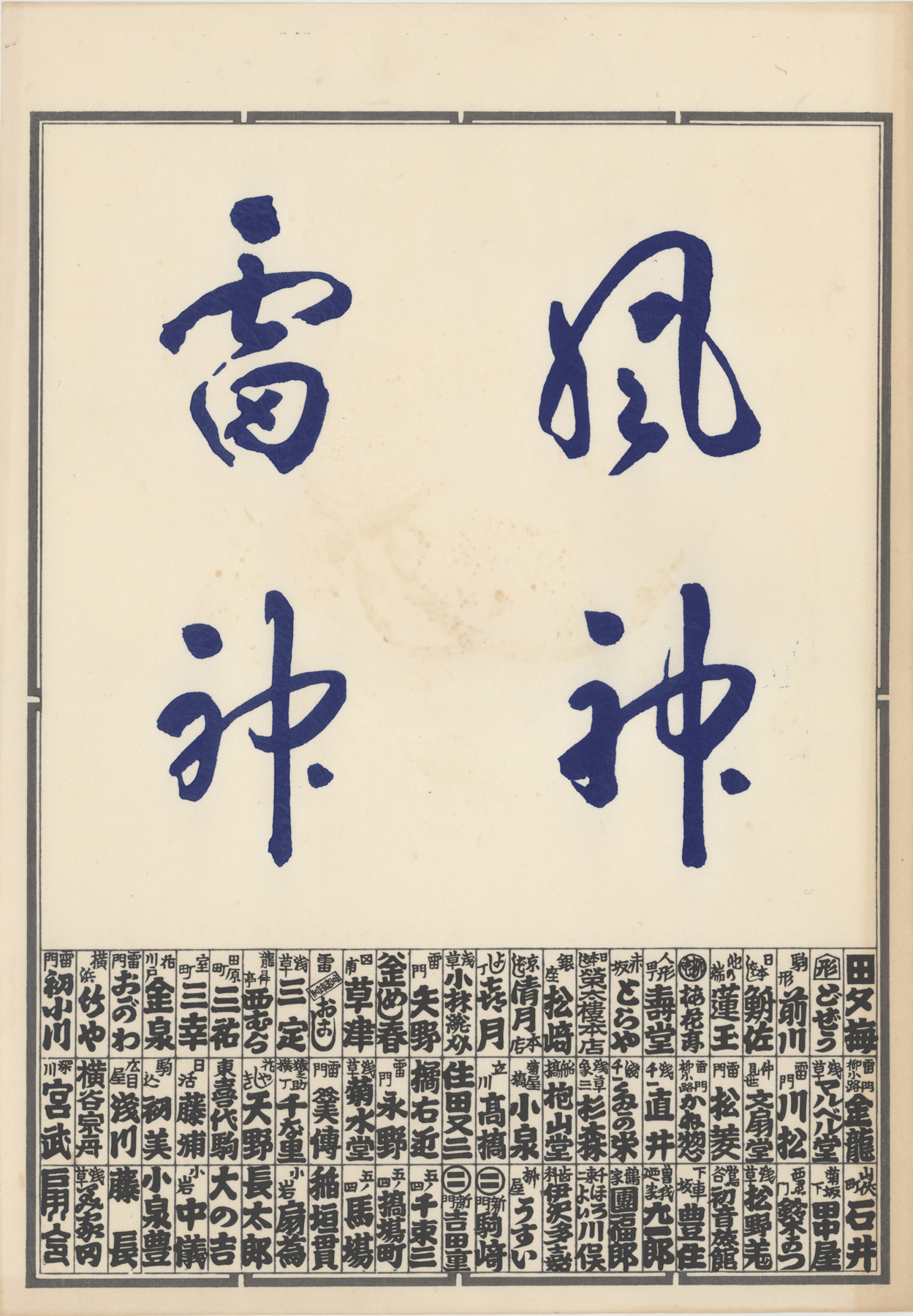

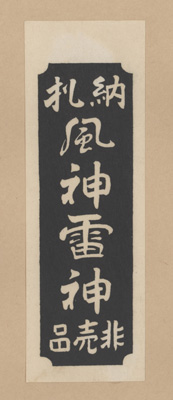

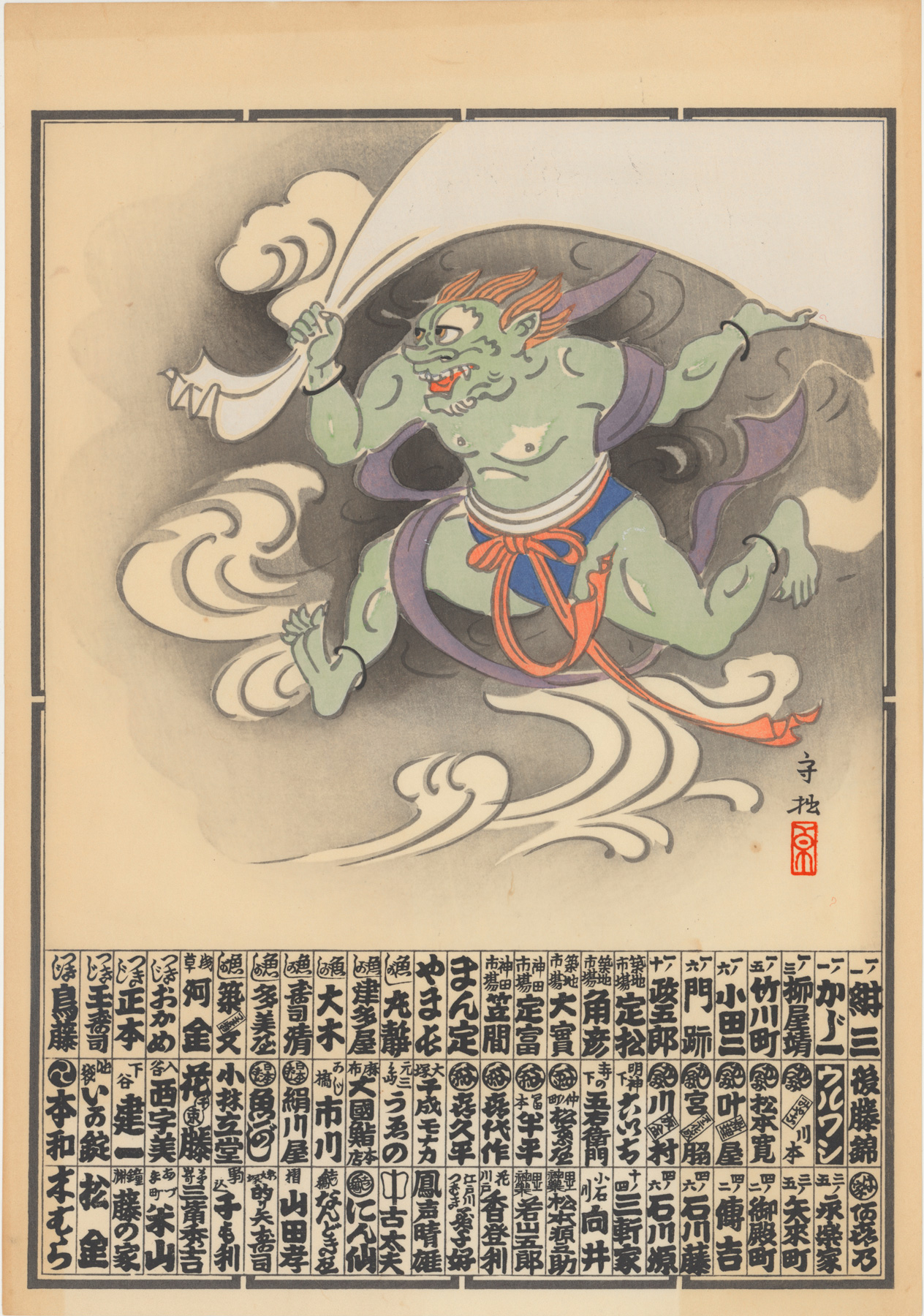

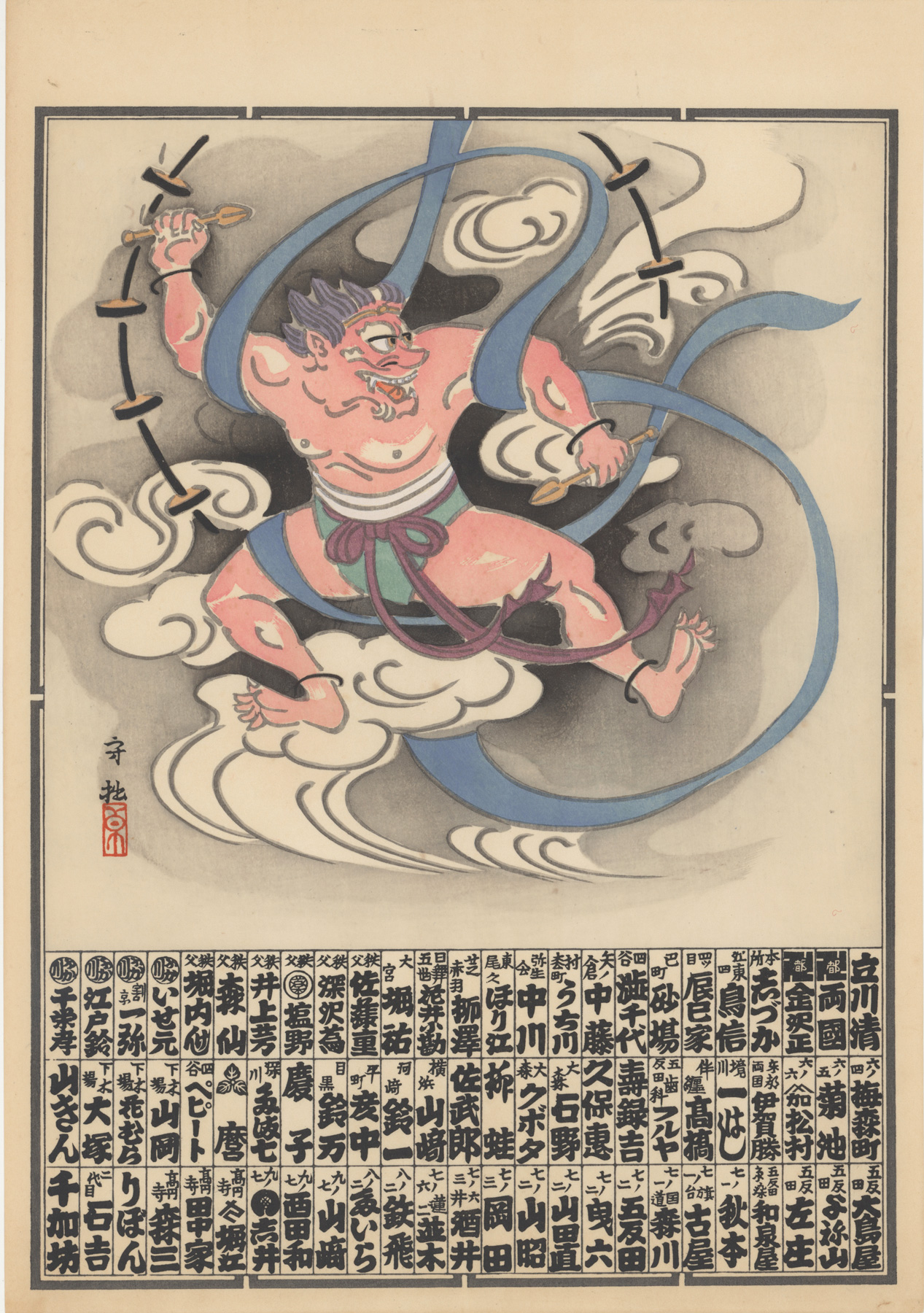

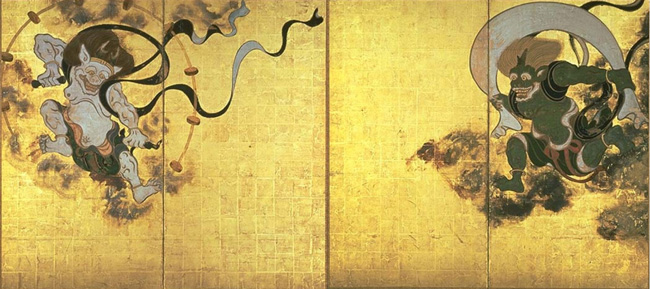

Pictured in this set of woodblock prints are the Buddhistand Shinto gods of wind, Fūjin 風神, and thunder, Raijin 雷神,whose names are written in calligraphic form on the cover print. All three prints were placed in an envelopewith the above label adhered to it noting that they were “not for sale.” It is likely these prints, designed by a nihonga artist who signed his name 守拙 Shusetsu,were commissioned by a nōsatsukai [anassociation of devotees of nōsatsu (Japanese votive slips)] and meant for distribution to members, hence they were“not for sale”. The names of the members of the nōsatsukai appear as small votive strips in the bottom portion ofeach print, 75 slips on each of the three prints. While the prints are undated,they are most likely a 20th-century production.

Fūjin and RaijinVotive Prayer Slips and Their Descendants

This set of woodblock prints are descendants of early votiveprayer slips (nōsatsuor senjafuda), left as offeringsat Buddhist temples by pilgrims. This practice, according to legend, dates toaround 987-988 when “the retired priestly Emperor Kazan wrote and presented… apoem (waka) at Kokawa temple whichwas devoted to the goddess of mercy, Kannon.”1 Votive offerings could be hand-written notes, engravings on stone orwood, paintings on wood, or woodblock prints, the earliest of which date to the12th century. Over time thepractice of leaving votive offerings, mostly as pasted pieces of paper bearingthe pilgrim’s name (sometimes referred to as daimei nōsatsu) on Buddhistshrine buildings, waxed and waned as authorities eased and tightened sumptuarylaws, limited Buddhist worship and promoted Shintoism, and shrines themselves discouraged thepractice. It was to reach its peakduring the Edo period and “became formalized with the establishment of group ofenthusiasts called nōsatsukai who organized theproduction of votive slips followed by communal trips to paste at shrines andtemples.”

Writing in 1916, a time of re-surging popularity for nōsatsukai, the American anthropologist Frederick Starr noted four stages of nōsatsufrom “pious offerings left at temples by pilgrims,” to the development of aninterest by those making such offerings in “the slips left by others”, then to when “those who were collecting nōsatsu,anxious to increase their collections, exchanged with others for placards . . .not in their possession,” and finally to “exchange on a large scale . . . atmeetings [where] special nōsatsu with elaborate and beautifuldesigns . . . were made for the occasion.” He further noted that while all fourstages were successive in nōsatsu history, “all four stillcontinue.”2

In describing these large scale exchange meetings, sometimesinvolving hundreds of nōsatsukai members, Starr writes:

[They are] among the most democratic gatherings in Japan. No other assemblage in Tokyo, probably, would represent so many social groups. Most of the members, of course, are not society folk. At the first meeting we attended, impressed by the diversity, we made enumeration. Among those present were a renting-agent, a sign-maker, a letter-writer, a brush-maker, a sauce-seller, a painter, a lantern-maker, a copyist, a poet and a coal-seller. Where else in Japan could one find such an aggregation meeting on terms of absolute equality?3

The themes chosen for kōkanfuda were many andvaried including religious, seasonal, historical, literary images or thoserelated to the craft or occupation of the members. Especially popular where depictions of theseven lucky gods and animals of the zodiac.

Over time the size of kōkanfuda grew into ōban (approximately 10 x 15 in.) and even larger sizeprints. As ukiyo-e artists and craftsmenwere often part of nōsatsukai, a stylistic linkdeveloped between kōkanfuda and ukiyo-e. As with privately commissioned surimono, kōkanfuda often were deluxeproductions, sparing no expense.

The notched outline of standard fuda was used on these larger prints to differentiate them fromsingle sheet ukiyo-e of the same size, as we see on this collection’s kōkanfudawhich employ the convention called komochikiof a thick and thin black line framing the subjects, a popular Edo textilepattern thought to reflect iki taste (Edo chic).

1 Japanese Popular Prints from Votive Slips to Playing Cards, Rebecca Salter, University of Hawai'i Press, 2006, p. 94.

2 "Folk Toys and Votive Placards: Frederick Starr and the Ethnography of Collector Networks in Taisho Japan", Henry D. Smith II, 2012, p. 40.

3 "The Honorable Placards Club", Frederick Starr appearing in ASIA The American Magazine on the Orient, American Asiatic Society, Volume XXI, NO. 2, February 1921, p. 121.

Print Details

| IHL Catalog | #1686a-d |

| Title or Description | Calligraphic Cover Sheet, Fūjin the Wind God, Raijin the Thunder God and Envelope with Label |

| Artist | Shusetsu (active c. 1900) |

| Signature |   appearing lower right on IHL #1686c and lower left on IHL #1686d |

| Seal | unread artist's seal as shown above |

| Publication Date | not dated - likely 20th century |

| Publisher | unknown, but likely commissioned by a nōsatsukai |

| Impression | excellent |

| Colors | excellent |

| Condition | excellent - some discoloration, possibly foxing to cover print and minor toning to all prints |

| Genre | kōkanfuda |

| Miscellaneous | |

| Format | vertical oban |

| H x W Paper | each print: 14 5/8 x 10 1/8 in. (37.1 x 25.7 cm) envelope: 15 3/16 x 11 1/4 in. (38. x 28.6 cm) |

| H x W Image | each print: 13 1/8 x 9 9/16 in. (33.3 x 24.3 cm) |

| Literature | |

| Collections This Print |