Prints in Collection

Biography

Tamamura Hokuto 玉村方久斗 (1893-1951) was born in Kyoto. His given name was Zennosuke which he continued to use for his writings and traditional Japanese paintings. He graduated from the Kyoto Municipal School of Fine Arts in 1915 where he studied with Kikuchi Hobun (1862-1918). From 1915 until 1923 the artist contributed to the official juried Inten exhibitions. After 1923 he became active in the proletarian and dadaist art movements and published a number of artistic journals. He was a major figure in Japan's avant-garde movement. He produced prints using woodblock and lithograph techniques both in sosaku hanga style and in the traditional Japanese way by working with a carver and printer.Recent Exhibition - Tamamura Hokuto: Revolutionary of the Japanese-Style Painting at The National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto (January 8, 2008 through February 17)

Source: The National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto website http://www.momak.go.jp/English/exhibitionArchive/2007/361.html

TAMAMURA Hokuto (Zennosuke; 1893–1951) was born in the central ward of Kyoto to a family that ran a shop dealing in geta,a type of Japanese footwear. He graduated from the Painting Departmentof the Kyoto Municipal School of Arts and Crafts in 1911, and went onto study under KIKUCHI Hōbun at the Kyoto Municipal Fine Arts College. Upon graduating in 1915, he founds Mitsuritsu-kai, an association forstudying and exhibiting nihonga (Japanese-style painting),with his colleagues from the two schools, including OKAMOTO Shinsō,KAINOSHŌ Tadaoto, and IRIE Hakō. He also submits Inariyama, Kyōgokokuji, Kiyomizudō to the 2nd Saikō Inten(Reorganized Japan Fine Arts Academy Exhibition), where his work isaccepted for the first time. In 1916, he relocates to Tokyo to studyat the Academy, and in 1918, he submits Ugetsu Monogatari (Tales of Moonlight and Rain) to the 5th Saikō Inten. This time, he wins an award and receives a nomination as an associatemember of the Academy, and thus makes his mark. However, he expressesdislike for conventional nihonga and leaves the Academy aftersubmitting his work one last time to the 6th Saikō Inten.

The present exhibition will introduce the entire scope ofTamamura’s work—known until now merely in fragments—for the very firsttime, through approximately 140 works and materials, such as magazines.

1 G.G.P.G was a Dadaist magazine sponsored by Tamamura and its first issue appeared in June 1924.

Flyer from First Half of Exhibition (11-03-07 through 12-16-07)

Quixotic quest of a 'revolutionary'

Breaking away from the herd, exploring new artisticdirections and assuming time itself will bring the ultimate vindicationis one of the great romantic ideas of avant-garde painting in the 20thcentury. But rather than defining the field for generations ahead, suchan artist risks simply becoming obscure, or worse, forgotten.

At age 48 in 1943, nihonga (Japanese- stylepainting) artist Hokuto Tamamura (1893-1951) could ask exactly what itwas he had been doing up until that point. Despite a long career,Tamamura had yet to be included among the 190 members of thestate-selected Nihonga Inventory Control Association. To assuage thesleight, he came to consider himself the 191st member, adopting thepersonal artistic seal of "No. 191," with which he signed his paintings.

The passage of time has been unkind to Tamamura. Workshave been lost or destroyed, and what, when and where he exhibited isoften a matter of conjecture. It is only recently, at Kyoto's NationalMuseum of Modern Art in "Tamamura Hokuto: Revolutionary of theJapanese-Style Painting," that the artist's oeuvre, previouslyknown only in fragments, has been assembled. But the issue remains asto whether Tamamura will now be recognized as a pioneer or remain acontemporary curiosity when the exhibition doors close.

Tamamura attended the painting department of the KyotoMunicipal School of Arts and Crafts before joining the Kyoto MunicipalFine Arts College, from which he graduated in 1915. Though he studiedunder Kyoto nihonga luminary Hobun Kikuchi at Kyoto Municipal, Tamamuraremained aloof from conventional Kyoto painting circles. Instead heformed the Mitsuritsui-kai with associates from his two schools, with aview to studying and exhibiting nihonga.

His earliest work was a loose, colorful and simplifiedversion of literati painting. In 1915, works submitted to theprestigious Inten (Reorganized Japan Fine Arts Academy Exhibition) wereaccepted, and after the show, he moved to Tokyo to strengthen theconnection to the organization. (It may have also had to do withescaping family discord.)

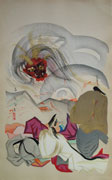

| The move was initially a good one for Tamamura, and in1918 he won the Inten's Chogyu Prize for his picture scrolls UgetsuMonogatari (Tales of Moonlight and Rain.) Regrettably, the originalswere destroyed in the 1923 Great Kanto Earthquake, and Tamamura paintedthe versions on display in the current exhibition between 1923 and '24. Ugetsu Monogatari was a series of supernatural tales penned byAkinari Ueda in the 18th century, and Tamamura's visual andcalligraphic reworking of the text in nine scrolls tends toward ascratchy, rough finish. He focused on sensationalistic visual momentsfrom the tales — in particular, a grotesque and nearly naked CannibalPriest who gorges himself on flesh atop a ground red with blood. But in 1920, Tamamura's submission to that year'sInten was rejected, so he left the association and never again had anyaffiliation with Japan's other major arts organizations. From here onin, he pursued a succession of supposedly avant-garde groupings thatmight better be |

termed fringe movements, and which culminated in aseries of group exhibitions named with supreme self-confidence —"Hokuto Society."

Withdrawing from the Inten led Tamamura's artisticactivities to take on breadth. Not only did he join avant-garde groupssuch as Daiichi Sakka Domei (Primary Artists' Alliance), Sanka andTan'i Sanka (Unit Sanka), he began to exhibit geometrical sculpturalworks based on a Russian Constructivist style similar to that ofVladimir Tatlin, and took to playwriting, printmaking, and typography.In 1925, he even designed his own house in Constructivist Sanka-style.

In hatching the Hokuto Society in 1930, Tamamurareturned to nihonga with the aim of reconceiving the nature of themedium. Despite whatever revolutionary fervor he had envisioned in theabove activities, Tamamura's return to form led him to depict highlyconventional, airily Impressionistic scenes of urban contentment, withoccasional forays into themes from Japanese literature and history. Inhis final decade's work, a proclivity for odd combinations of imageryalso arose, as in the telephone wire "Insulators and Shower (PhoenixTree)" (1943) or "Goldfish Bowl on the Tree" (1943).

With his "Sanka house" demolished and the artist'sbold but quickly discontinued sculptural work destroyed, appraisingTamamura's "avant- gardeness" would fall to his nihonga, given that"No. 191" was adamant about his allegiance to the art form.

While an undeniable fluidity and elegance inform workssuch as Four Landscapes: Afterglow (1926), his vistas often becomedirty accretions of layered washes with figures that fade into theterrain, as in Hougen Monogatari (War Tale) — Killed (1928). And evenin works from the '30s where Tamamura claimed he was reconceiving themedium, it is difficult to see where he was heading — he mostly took uprun-of-the-mill subjects from Japanese art history or created works intraditional pigments that took on nuances of oil paint, before quicklyabandoning such projects.

Thus, in the final assessment, Tamamura seems less the revolutionary than the dilettante.

A Contemporary's Comment

Source: Shredding the Tapestry of Meaning: The Poetry and Poetics of Kitasono Katue (1902-1978), John Solt, Harvard University Press, 1999, p.26Tamamura’s contemporary, the avant-garde poet and writer Kitasone Katue (1902-1978), wrote about his friend Tamura:

“Tamamura made a living painting chrysanthemums and other objects in Japanese style (Nihon-ga). He had been in the Fine Arts Academy but, after quitting, was considered a heretic. He was rich and would buy books about new art trends in the West. My first encounter with the Bauhaus was when Tamamura bought all the volumes in the Bauhaus series and showed them to me. He published Takahar (Plateau), but gave it up and issued a new art magazine, Epokku (Epoch), in which expressionism and cubism were presented with examples of the works.”