About This Print

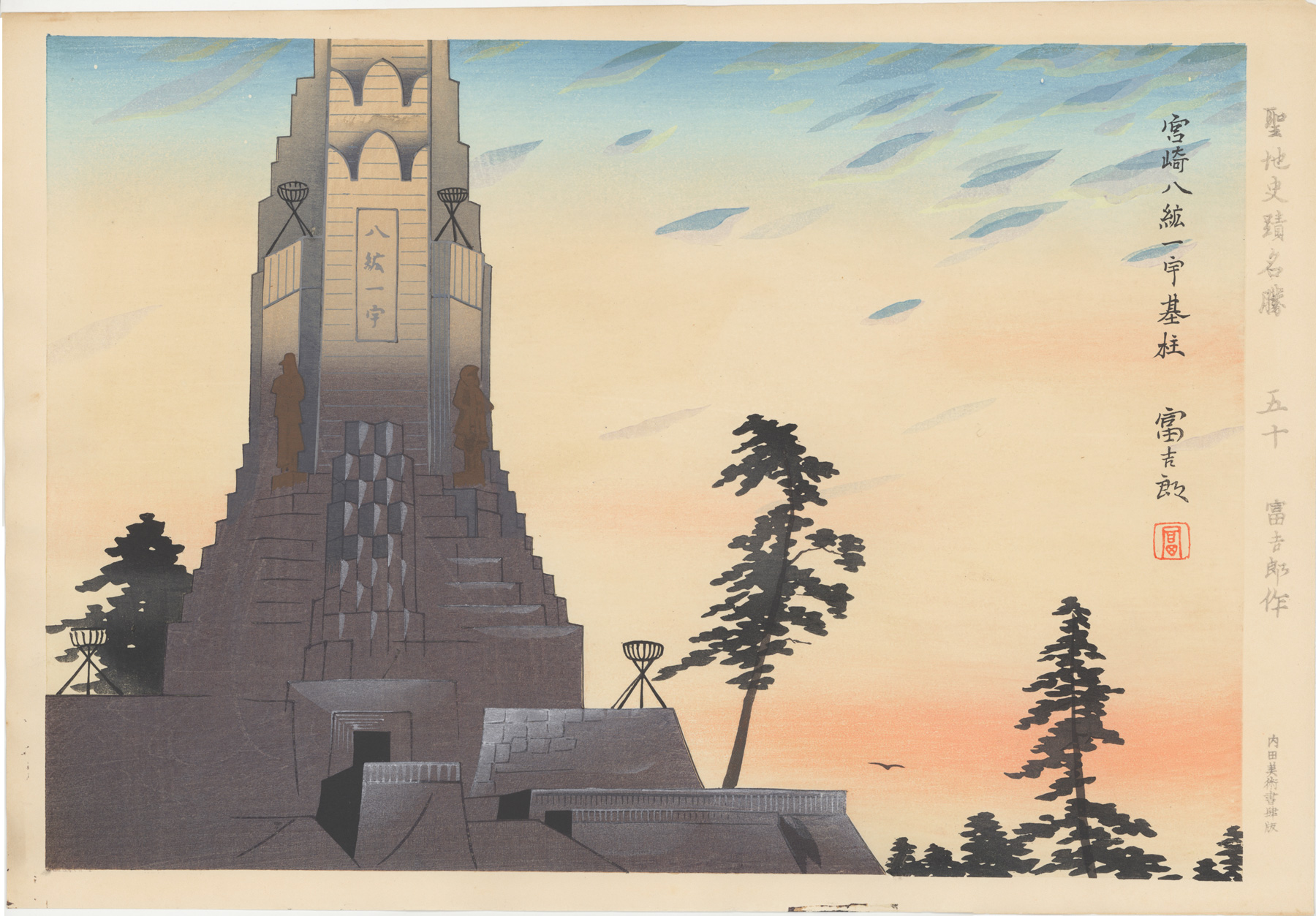

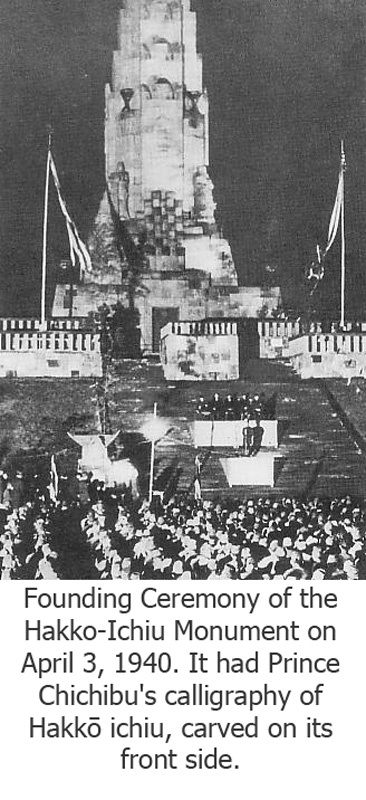

Print number fifty of the fifty print series Scenes of Sacred and Historic Places (Seichi Shiseki Meisho) published by Uchida Woodblock Printing Company in 1941. It is perhaps the ultimate nationalist print in the series, depicting Hakkō Ichiu Tower in Miyazaki erected in 1940 to commemorate the 2,600th anniversary of the mythical ascension of Japan's first emperor, Jimmu, on 11 February 660 BC.

"Nineteen forty [the year tower was erected] was also the fourth year of warfare stemming from theChina Incident of July 1937, a conflict by then already lasting far longer thanfirst anticipated. In the midst of widespread efforts to maintain the country'swill to fight, the 2,600th anniversary of Jimmu's achievement was exploited asa source of nationalistic inspiration.

"Inexplaining the project to the prefectural assembly on December 5, 1938, the governorspelled out this design in the following terms. One aspect [of the plan] isthat at the time of the 2,600th anniversary celebrations, the extent of thenation's might, the nation's condition, be written somewhere on it, to showwhat the population is at the time, how much land there is, what the strengthof the nation is, in other words, to show how far the Imperial Virtue hasspread ... so that at the 2,700th anniversary, by looking back one hundredyears it can be seen ... how far Japan's might as a nation has grown.

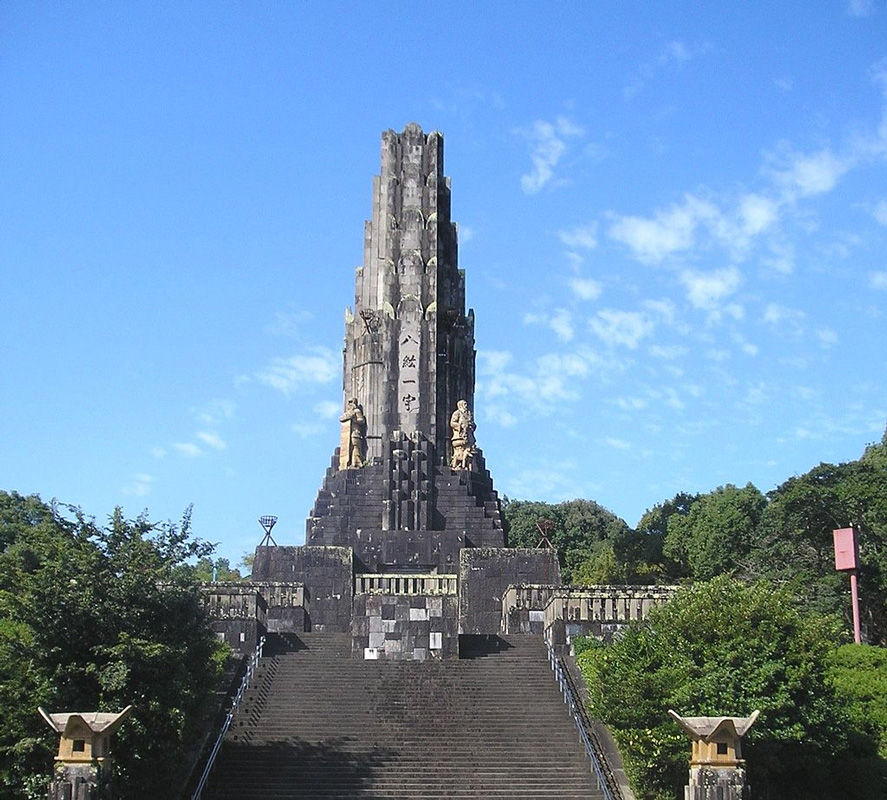

"The tower is thus a symbolic statement that the essence of the nation'shistory is continual expansion; its decoration further stressed that this expansion had a military aspect and that it began from Hyūga. Set at the tower'sentrance is a large pair of bronze doors, the work of the same sculptor whodesigned the monument as a whole, which feature a large bas-relief nearlycovering their combined width and depicting Jimmu's departure on his journeyeast. According to the Nihon shoki account, Jimmu's party sailed from Hyūga upthe Inland Sea toward Yamato. In suitable fashion, the image on the tower'sdoors is that of a fleet of warships, ready to launch forth with banners flyingand sails unfurled. Each vessel is manned by rows of soldiers in armor, itsgunwales lined with their spears and shields. Expansion wasjustified by linking military images with symbols of unassailable authority:Shinto worship and the imperial institution. The main portion of the tower is afusion of images representing warfare and religion, consisting principally ofa spear, a shield, and a gohei, the wand of paper streamers used in Shintoceremony. Spears are depicted in relief on the two faces not bearinginscriptions. Each of the tower's four faces, seen head on, is built torepresent a series of five shields, stacked in receding fashion from lowermostto uppermost, giving a stepped contour to the tower's upper reaches.Accordingly, as the eye scans downward from the tower's top, its profile jutsout by degrees both right and left in symmetric fashion, a shape intended toresemble a gohei. In explaining this design, Governor Aikawa commented upon theritual use of this item to purify. Our nation was founded with the spirit ofdriving away sin and pollution, not only from Japan but from the entire world,and, nurturing these lands, of making them into one house.

"Hakkō ichiu was among the many militaristic slogans soon blackened inschool textbooks and banned from the press by GHQ censors. A unit of theoccupation arrived in Miyazaki in November 1945, and its commander made itclear that aspects of the tower were 'undesirable.' Specificallycited were the slogan on the front, the plaque on the rear, and a large ceramicstatue on the tower's base, made in imitation of a Kofun-period haniwa warriorin full battle dress. These were all removed in January 1946. Taking a hintfrom the commander's suggestion that they be replaced with more peaceful items,the tower soon came to be referred to as Heiwaidai ("Peacetower"). Miyazaki counted heavily on tourism for its economic recoveryin the late 1940s and 1950s, promoting the scenic coastline of a newly creatednational park south of the city and cultivating an image of the region as aMecca for honeymooners. The prefecture officially renamed the area around thetower, which had become a regular stop for tour buses since 1950, as HeiwadaiKōen (Peace Plateau Park) in 1957."

ARTICLE HISTORY FEB 10, 2015

MIYAZAKI – A monument in the city of Miyazaki built to glorify Imperial Japan’s occupation of Asiannations and later rededicated as the city’s Peace Tower has been a source of local discomfort fordecades.

In 1965, authorities restored an Imperial-era slogan on the 36-meter stone tower, despite oppositionfrom critics who felt it sent the wrong message.

The four-character phrase is “Hakko Ichiu” (Eight Corners of the World Under One Roof). The sloganwas used by the Imperial Japanese military as it sought to create “a new world of human fraternityunder the Japanese emperor.”

The tower was built in 1940 to commemorate the 2,600th anniversary of the ascension of EmperorJimmu, the nation’s first emperor.

Made of stones from around the Japanese empire, it was used to rally people’s fighting spirit in WorldWar II but was later scorned as a symbol of that ill-fated venture. It eventually survived as a symbol ofpeace.

Ikuko Yasuda, 90, was one of many high school girls drafted to help level the ground for the tower’serection.

A year before the war ended, Yasuda worked at an air base in Miyazaki and saw off many young pilotson kamikaze suicide missions.

“I couldn’t say a word and felt helpless,” Yasuda recalled. “We should call Aug. 15 the anniversary ofJapan’s ‘defeat in the war,’ instead of ‘end of the war,’ and recognize with a sense of remorse that thepostwar era started from something negative rather than from zero.”

Some people in Miyazaki are baffled by how a symbol of the Imperial invasion of Asia became asymbol of peace.

Keiichiro Saita, 71, set up an amateur research group that for the past quarter of a century has beenstudying the tower and its history.

Saita agrees with a local history book that says the words Hakko Ichiu were removed from the tower atthe request of the U.S. military after the war, and that it was rededicated as a tower “built in the hopesof peace.”

Heiwadai Park was one of the starting points for torch relays for the 1964 Tokyo Olympic Games. Withthe park drawing attention at a time when the Imperial family was the object of increasing popularinterest, the prefectural government accepted a request from the local tourism association toreinscribe Hakko Ichiu on it.

The work was carried out quickly before opposition could crystallize, Saita said. He considers thatunfortunate.

The tower bears testimony to Japan’s invasion of Asia as it was built with stone brought from China,Taiwan, Korea and other places under Japan’s control, Saita said. But as there is no signboard in thepark to explain the historical background, it cannot be called a “peace tower in the real sense of theterm unless the negative part of its history is squarely looked at,” he said.

In the 1960s and 1970s, Miyazaki became a popular destination for newlyweds after Takako Shimazu,the fifth and youngest daughter of Emperor Showa, and her husband Hisanaga Shimazuhoneymooned there in 1960.

The tower itself has survived the changing tides of history, Yasuda noted, and as a survivor of conflict it“allows us to pass down memories of the war from generation to generation.”

Vividly remembering the days just before World War II, Yasuda is worried by whether the Abegovernment’s reinterpretation of the war-renouncing Constitution might lead the nation into war onceagain.“Japan must never go to war because it is a small country that cannot live by itself,” she said.

The Series - Scenes of Sacred and Historic Places

The print artist Tokuriki and the publisher Unsōdō created two series of prints to mark Kigen 2600, or the 2600th year of Japan's mythical founding as a nation. The first, a paean to Mount Fuji, a sacred site of pilgrimage and worship, titled Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji, harkened back to Hokusai’s famous 1831 series of the same name. The second series, Scenes of Sacred and Historic Places, capitalized on the nationalist ideology that Japan was a divine land, presenting overtly nationalistic landscapes including shrines, temples, castles, places associated with the divine origins of Japan, Meiji era history and samurai

culture.

In his commentary on this series, the artist wrote that his devotion to these sites is intended to demonstrate to the people the dignity of the national polity, going on to say that he advocates prints as a means of providing comfort and pleasure to the wholesome citizens of the nation.

This series was extremely popular with domestic and foreign buyers who purchased one thousand copies within a short time after issuance.1 I imagine that foreign buyers were enchanted by the lovely scenes with much of the import of each print escaping them. In the 1950s, six prints from this series were re-printed under the title The Album of Famous Views of Japan and eight additional prints were re-printed under the title The Eight Views of Japan. Later printings omit the information in the margin and some position the artist's signature and print title within the image in a different location from the original issue.

For images of all the prints in the series, go to the website of Ross Walker's Ohmi Gallery at http://www.ohmigallery.com/Gallery/Tokuriki/SacredPlaces.htm.

1 Modern Japanese Woodblock Prints - The Early Years, Helen Merritt, University of Hawaii Press, 1998, p. 89.

In his commentary on this series, the artist wrote that his devotion to these sites is intended to demonstrate to the people the dignity of the national polity, going on to say that he advocates prints as a means of providing comfort and pleasure to the wholesome citizens of the nation.

For images of all the prints in the series, go to the website of Ross Walker's Ohmi Gallery at http://www.ohmigallery.com/Gallery/Tokuriki/SacredPlaces.htm.

1 Modern Japanese Woodblock Prints - The Early Years, Helen Merritt, University of Hawaii Press, 1998, p. 89.

Margin Annotations of Original Edition (top to bottom) and Print Title Within Image

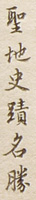

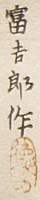

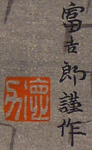

series title Seichi Shiseki Meisho 聖地 史蹟 名勝 |  五十 (50) |  Tomikichiro kin saku 富吉郎 謹作 (respectfully made by Tomikichiro) followed by oval seal1 |  内田美術書肆版 (Uchida Fine Art Shop) followed in seal form by Fukyo Fukusei (Reproduction forbidden)) | Print Title  宮崎八紘一宇基柱 (Hakkō ichiu kijū) |

1 possibly a reproduction of an old censor's seal

The title of each print appears within the image area along with the artist's signature and seal. The artist's signature is comprised of the artist's name 富吉郎 (Tomikichirō) either by itself or followed by the single kanji character 作 (saku "made by") or by the character 謹 (kin "respectfully") followed by 作, as shown below.

| IHL Catalog | #1663 |

| Title | Hakkō Ichiu Tower in Miyazaki 宮崎八紘一宇基柱 [Hakkō ichiu kijū] |

| Series | Scenes of Sacred and Historic Places (also seen translated as "Collected Prints of Sacred, Historic and Scenic Places") 聖地 史蹟 名勝 Seichi Shiseki Meisho |

| Artist | Tokuriki Tomikichirō (1902-2000) |

| Signature |  |

| Seal | see above - 富 Tomi seal |

| Date | September 1941 |

| Edition | original (first) edition |

| Publisher | Uchida Bijutsu Shoten |

| Impression | excellent |

| Colors | excellent |

| Condition | excellent - minor toning |

| Genre | shin hanga (new print); fūkeiga |

| Miscellaneous | 五十 #50 in series |

| Format | horizontal ōban |

| H x W Paper | 11 3/8 x 16 1/2 in. (28.9 x 41.9 cm) |

| H x W Image | 10 3/8 x 15 (26.4 x 38.1 cm) |

| Collections This Print | Penn Libraries, Rare Book & Manuscript Library - Rare Book Collection Call no.: Portfolio NE1325.T65 A4 1940 |

| Reference Literature |