About This Print

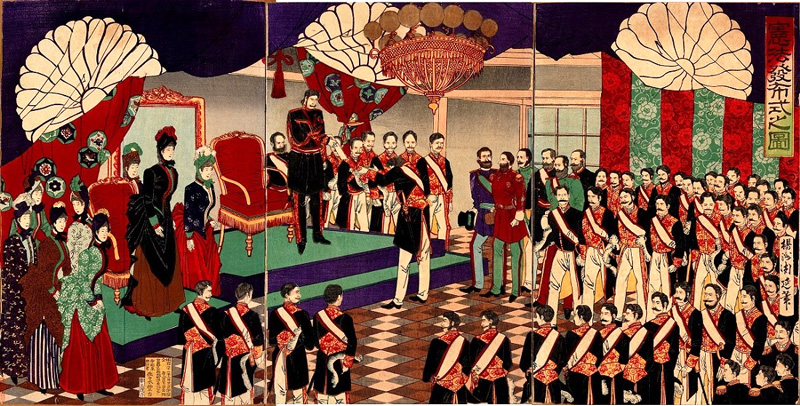

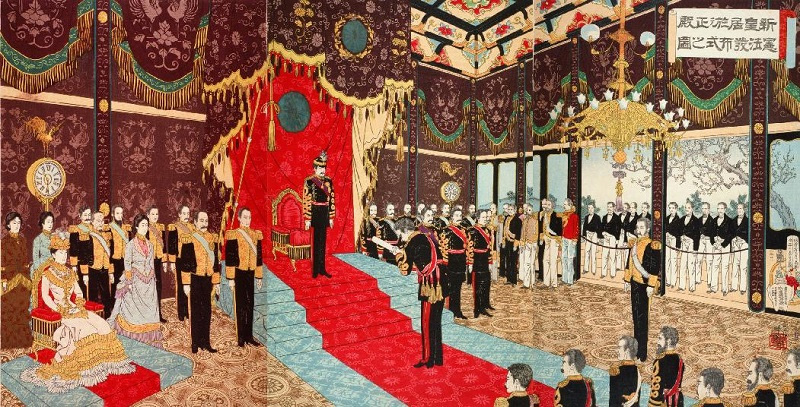

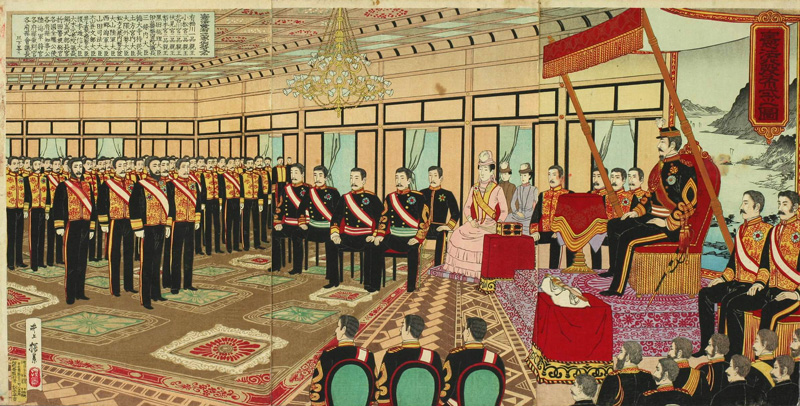

One of many prints depicting Emperor Meiji’s February 11, 1889 public pronouncement, following a private ceremony in the Palace Sanctuary, of Japan’s first constitution which came into effect on November 29, 1890. Kokunimasa, as with the other artists who designed prints of the promulgation, did not attend the ceremony, which was limited to invited dignitaries, foreign and domestic, and eighteen members of the press1, and created this print from the published accounts, taking a requisite amount of artistic license as did the other artists.

Much information, including a printed seating plan, was disseminated prior to the ceremony, the public part of which was to take place in the emperor's new Throne Room. The emperor is seen in his admiral's uniform sitting in the most elevated position on his gyokuza (imperial seat), with the Sacred Jewel and Sacred Sword being held by two attendants below him, and the empress, in a pink western-style dress and bonnet, is seated to his left. Arrayed around him are the various dignitaries. Holding the constitution is Sanjō Sanetomi (1837-1891), the minister of the imperial household.

Following the morning promulgation ceremonies the emperor and his entourage left the palace in a stately procession, crossing Nijubashi, and travelling to the Aoyama Military Parade Field where the emperor inspected the troops. Thousands lined the route in a coordinated outpouring of support and joy. Another bevy of woodblock prints depicted this imperial procession including this collection's print Illustration of [The Emperor’s Carriage] Departing the Imperial Palace [over] Nijūbashi.

1 The eighteen press spots were allocated as follows: ten from Tokyo, five from the provinces and three from English language newspapers.

The Promulgation of the Constitution

Imperial Rescript on the Promulgation of the Constitution Whereas We make it the joy and glory of Our heart to behold the prosperity of Our country, and the welfare of Our subjects, We do hereby, in virtue of the Supreme power We inherit from Our Imperial Ancestors, promulgate the present immutable fundamental law, for the sake of Our present subjects and their descendants.

Source: Emperor of Japan: Meiji and His World, 1852-1912, Donald Keene, Columbia University Press, 2002 p. 421-422.

On February 11, the anniversary of Emperor Jimmu’s accession [600 B.C.], the emperor promulgated the Imperial House Act and the Imperial Constitution at a ceremony held in the Hall for State Ceremonies. In the formal statement addressed to his ancestors read on this occasion, he attributed to their guidance the momentous events of this day. He vowed to abide by the provisions of the constitution.

The constitution was publicly pronounced at a ceremony held later that morning…. The description of the ceremony by Dr. Erwin Baelz, the German physician who served the imperial family, evokes the scene:

In front of the Emperor, somewhat to the left, were ranged the ministers of State and the highest officials. Behind were the chief nobles, among whom I noticed Kamenosuke Tokugawa, who, but for the Restoration, would now be Shogun; also Prince Shimadzu of Satsuma, the only one who (though wearing a western uniform) had his hair dressed in the old Japanese style. He cut a strange figure! Immediately to the left of the Emperor were the diplomatic corps. The gallery surrounding the hall had been opened to the other high officials and to a number of foreigners. The Empress followed with the princesses and the court ladies. The Empress wore a European dress, pin, with a train. On either side of the throne a high dignitary now stepped forward, one of them Duke Sanjo, formerly imperial chancellor, each of them with a roll of parchment. The one Sanjo held was the constitution. The Emperor took the other document, opened it, and read it in a loud voice. It contained the decision to give the people voluntarily the promised constitution. Then the Emperor handed the charter itself to the prime minister, Kuroda, who received it with deep reverence. Thereupon the Emperor nodded and left the hall, followed by the Empress and suite. The whole business lasted about ten minutes. Meanwhile salutes were being fired, and bells were being rung everywhere. The ceremony was dignified and brilliant. The only trouble was that the throne-room, a very fine apartment, is colored red, and was therefore too dark.

The 1889 constitution was the most advanced possessed by any Asian country and was more liberal than those of many European countries; but the insistence on the “sacred and inviolable” person of the Emperor and the rights of sovereignty invested in him indicates how far the constitution was from granting sovereign power to the people. The granting of the constitution nevertheless marked the beginning of representative government in Japan. Am imperial edict, issued on the same day, stated that a parliament would be convened in 1890 and that the constitution would go into effect the same day.

The Constitution - A Brief Summary

Source: A Modern History of Japan: From Tokugawa Times to the Present, Andrew Gordon, Oxford University Press, 3rd ed., 2014, p. 91-92.

The right of sovereignty of the State, We [meaning the emperor] have inherited from Our Ancestors, and We shall bequeath it to Our descendants.

So states the preamble of the constitution, investing the emperor with "unequivocal ... imperial sovereignty."

"Cabinet ministers were responsible to the emperor and not to the Diet. However, the prospect of direct imperial despotism was checked in a general way in the preamble, which went on to state that "Neither We nor [our descendants] shall in the future fail to wield the [rights of sovereignty], in accordance with the provisions of the present Constitution and of the law." In the constitution itself, the power of the bureaucracy in relation to the throne was bolstered by the requirement that cabinet ministers cosign all imperial orders. The constitution gave a special independence to the military general staff, via the "right to supreme command." This was article 11, which specified that the military was directly responsible to the emperor. The constitution granted a variety of civil rights to the people. All of these, however, were made conditional on "limits established by law."

The Diet, composed of an elected House of Representatives and a House of Lords, "had power to write and pass laws" [and] "the crucial power to approve or veto the annual state budget" which provided them with some leverage. While allowing for the direct election of Representatives, the first election law only enfranchised about 1% of the population, being based upon tax payments over a stipulated threshold.

In summary: "The promulgation of a constitution and the convening of an elected Diet meant that Japan was a nation of subjects with both obligations to the state and political rights. Obligations included military service for men, school attendance for all, and the individual payment of taxes. Rights included suffrage for a few and a voice in deciding the fate of the national budget. The fact that these rights were limited to men of substantial property is important.... Clearly the constitution was expected by its authors to contain the opposition. But to stress only the limitations place don popular rights by the Meiji constitution is to miss its historical significance as a source of future change. The undeniable fact was that a constitutionally mandated, elected national assembly - with more than advisory powers - now existed. This clearly implied that a politically active and potentially expandable body of subjects or citizens also existed. Indeed, as the oligarchs decided to adopt a constitution, they were acutely aware that such a body politic was in the process of forming itself and developing its own ideas about the political order.

For the complete text in English of the constitution see www.ndl.go.jp/constitution/e/etc/c02.html

Yōshū Chikanobu

Yōshū Chikanobu

Yōshū Chikanobu Adachi Ginkō

Hasegawa Chikuyō

PowerPoint Presentation Notes from 1-31-2017 Presentation

Illustration of the Ceremony for the Promulgation of theConstitution of Great Japan, June 1889

One of many prints depicting Emperor Meiji’s February 11, 1889 public pronouncement, following a private ceremony in the Palace Sanctuary, of Japan’s first constitution, which came into effect on November 29, 1890.

The artist did not attend the ceremony, which was limited to invited dignitaries, foreign and domestic, and eighteen members of the press. He created this print from the published accounts, taking a requisite amount of artistic license.

While the general public were not allowed to attend the public pronouncement of the constitution, for a few sen you could choose from over a dozen different prints (all looking very similar) that made you an intimate part of these historic events.

PowerPoint Presentation Notes from 1-31-2017 Presentation

| Illustration of the Ceremony for the Promulgation of theConstitution of Great Japan, June 1889 One of many prints depicting Emperor Meiji’s February 11, 1889 public pronouncement, following a private ceremony in the Palace Sanctuary, of Japan’s first constitution, which came into effect on November 29, 1890. The artist did not attend the ceremony, which was limited to invited dignitaries, foreign and domestic, and eighteen members of the press. He created this print from the published accounts, taking a requisite amount of artistic license. While the general public were not allowed to attend the public pronouncement of the constitution, for a few sen you could choose from over a dozen different prints (all looking very similar) that made you an intimate part of these historic events. |

Print Details

| IHL Catalog | #1104 |

| Title or Description | Illustration of the Ceremony for the Promulgation of the Constitution of Great Japan 大日本憲法発布式之圖 Dai Nippon kenpō happushiki no zu |

| Series | |

| Artist | Utagawa Kokunimasa (1874-1944) |

| Signature |  |

| Seal | Toshidama seal (see above) |

| Publication Date | June 1889 明治廿二年二月 (see publisher seal below) |

| Publisher | Fukuda Kumajirō 福田熊治郎 [Marks: pub. ref. 071; seal not shown] From right to left: 明治廿二年二月 日出版 Meiji 22nd year, 2nd month, [blank] day; publication 仝年二月日印刷 Meiji 22nd year, 2nd month; printing 印刷兼発行者 printing and publishing 日本橋長谷川町 Nihonbashi Hasegawachō [address] 十九?千 19? sen [price] 福田熊次郎 Fukuda Kumajirō |

| Impression | excellent |

| Colors | excellent |

| Condition | good – three separate unbacked sheets; minor wrinkling |

| Genre | nishiki-e; kaika-e |

| Miscellaneous | |

| Format | vertical oban triptych |

| H x W Paper | (L) 14 1/2 x 9 11/16 in. (36.8 x 24.6 cm); (C) 14 1/2 x 10 in. (36.8 x 25.4 cm) (R) 14 1/2 x 9 3/4 in. (36.8 x 24.8 cm) |

| Literature | |

| Collections This Print | Museum of Fine Arts, Boson 2000.283a-c |

| Reference Literature | "Le Jour Où: Le Japon se donne une Constitution" by Lionel Babicz, appearing in Le Figaro Histoire, Numéro 46, Octobre-Novembre 2019, p. 55 with credit to "Courtesy of The Lavenberg Collection of Japanese Prints" |

last revision:

4/28/2021

6/15/2020

3/29/2020