About This Print

Source: Impressions of the Front: Woodcuts of the Sino-Japanese War, Shunpei Okamoto, Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1983, p. 29."Once the Japanese forces invaded Chinese territory, they engaged in a full-scale attack on Hushan. A severe battle began at dawn on October 25. The Japanese suffered one hundred twenty casualties, but the Chinese losses were countless. The print shows Chinese troops dropping into the swirling river as they are fired upon from both banks. It is said that corpses of Chinese soldiers and horses blocked the river. Hushan was taken by 10:30 AM, and the Chinese defense was forced further back in Manchuria to Kuliencheng. This print was issued on October 26."

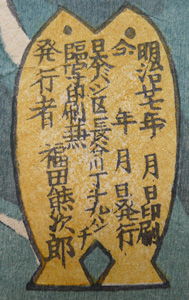

This print was issued with two different title cartouches as shown below. The cartouche on the left is from the collection of the Philadelphia Museum of Art and the top characters 十月廿六日号外 tell us that this print is "An 'extra' issued on October 26". The cartouche on the right is this collection's print which doesn't include the "extra" notation.

To put this in context, prints of battle scenes were often issued before the actual battle took place. Upcoming battles could be gathered from news reports and other sources. Since the depiction of battle scenes was somewhat formulaic, the artist didn't need to be too concerned about depicting what actually would occur. It is likely that this collection's print without the "extra" notation was issued before the actual battle and that when the battle actually occurred on October 25th, the publisher added the "extra" notation to make it seem that the print was a true depiction of what occurred. Likely an effective advertising ploy. It should also be noted that the publisher seal which contains the publishing date is identical on both prints and it only indicates the year, with the month and day being left blank.

There are instances when prints announcing specific battles have been issued, only to have that battle not occur, as is the case of this collection's print Picture of the Hard fight at Fenghuangcheng, which depicts a battle that was planned by the Japanese as a present for the emperor on his birthday, but did not occur due to a retreat by the Chinese.

Battle at Hushan

Source: The Sino-Japanese War of 1894-1895: Perceptions, Power, and Primacy, S. C. M. Paine, Cambridge University Press, 2003, p. 199-200.Japan’s First Army, under Field-Marshall Count Yamagata Aritomo, had left P’yongyang to reach the Yalu on October 23. The fifty-six-year-old Yamagata was the father of the modern Japanese army and leading Meiji-period statesman. Not only had he overseen the introduction of national conscription in 1873, the reorganization of the army along Prussian lines in 1878, and the adoption of an independent General Staff system, but in the 1880s he had also reorganized the national police force and system of local government. As prime minister from 1889-1891, he had helped introduce the imperial rescript on education, westernizing Japanese educational institutions. After the war he described his command appointment in the war as the “happiest moment in my life.”

His plan followed Napoleon’s successful tactic of making a feint to the front while delivering the main blow on the flank at Hushan. He planned to use a small force to attack the left wing of the enemy in hopes of turning its flank and also as a feint to disguise the movements of the main body of troops. These he planned to concentrate on the center of the Chinese position. To do this, the troops first had to cross the Yalu. The Japanese had learned their lesson at P’yongyang and this time had made careful preparations to ford the river. On the night of October 24, they erected a pontoon bridge at Uiji to get the main body of their troops across the Yalu. On the next day, the main attack began with a simultaneous diversionary attack on the Chinese flank. This meant that the Chinese were caught between two lines of fire. After defeating the Chinese forces at Hushan on the 25th, the Japanese planned to attack Jiuliancheng in the early hours of the 26th. According to a military analyst, “The Chinese garrison (at Jiuliancheng) which might have inflicted great damage on the hostile army from behind battlements of solid masonry, silently decamped during the night, keeping up a desultory fire in the meantime in order to encourage the belief that they intended to retain possession of the stronghold.” When the Japanese scaled the city walls, they found it deserted. The same was true for Andon. As usual, the Chinese left behind enormous quantities of weapons and rice and , in doing so, once again provided commissariat and logistical services for the invading Japanese army.

Print Details

| IHL Catalog | #319 |

| Title (Description) | Japanese Troops Attack the Chinese Cavalry in the Vicinity of Hushan 虎山附近騎兵ヲ攻擊ス [虎山附近騎兵ヲ攻撃ス] Kozan fukin kihei o kōgekisu |

| Artist | Utagawa Kokunimasa (1874–1944) |

| Signature |  |

| Seal |  |

| Pub. Date | October 1894 (Meiji 27) (as shown below on publisher seal) |

| Publisher | Fukuda Kumajirō [Marks: 30-046, publisher ref. 071] |

| Engraver | |

| Impression | excellent |

| Colors | excellent |

| Condition | fair-backed; margins trimmed to image; vertical folds where panels joined |

| Genre | nishiki-e; senso-e |

| Miscellaneous | |

| Format | vertical oban triptych |

| H x W Paper | 14 x 27 3/4 in. (35.6 x 70.5 cm) |

| Literature | Impressions of the Front: Woodcuts of the Sino-Japanese War, Shunpei Okamoto, Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1983, p. 29, pl. 35. |

| Collections This Print | Philadelphia Museum of Art 1976-75-150; National Library of Australia Bib ID7285151 (part of a collection of S-J War prints in a collector book) |

3/29/2020