About This Print

Source: Museum of International Folk Art http://www.internationalfolkart.org/exhibitions/past/moonweb/section2/059.htm

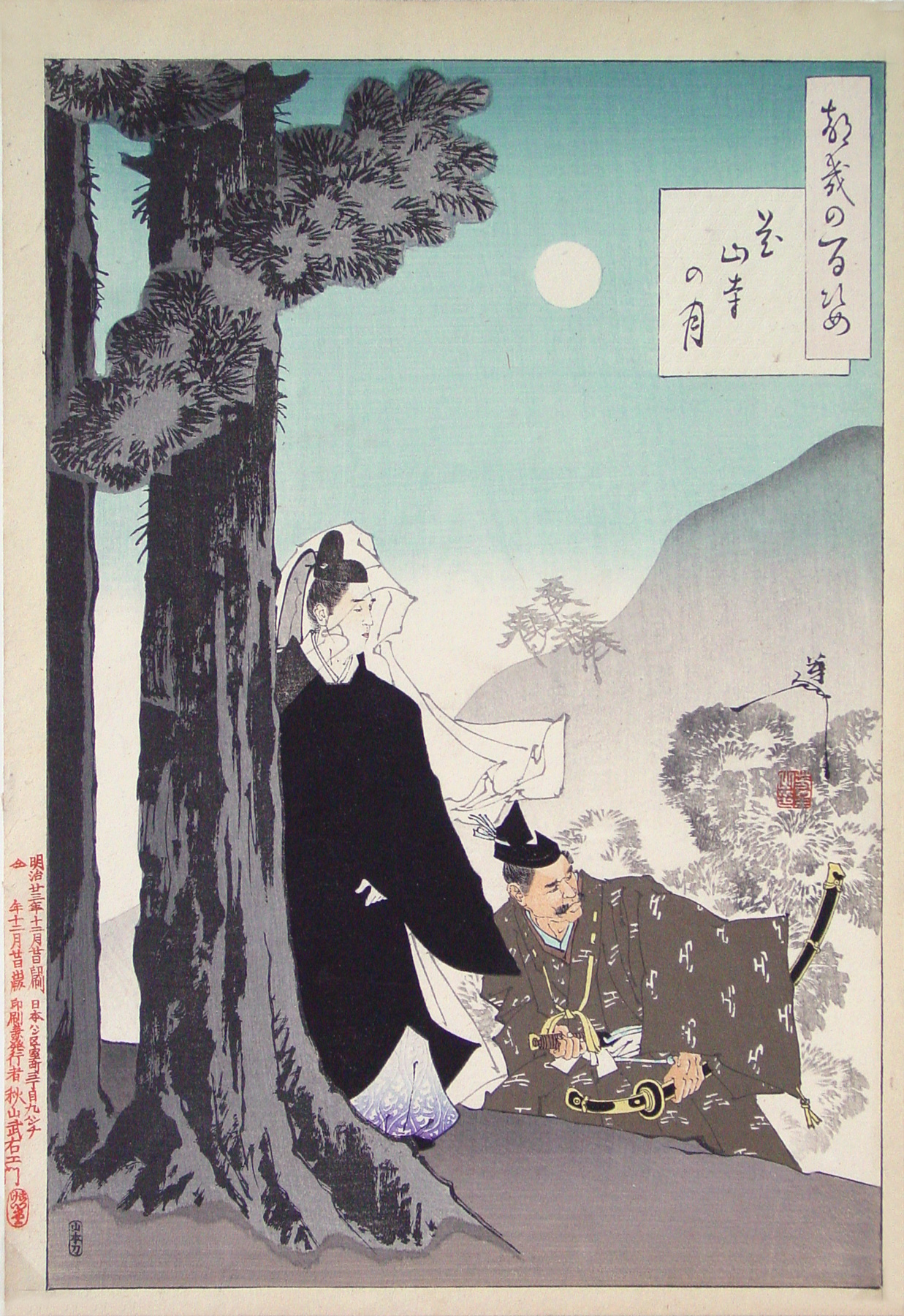

The young Emperor Kazan flees under guard at night to Kazan temple. Because of a court intrigue, Kazan was forced to abdicate in A.D. 986 after reigning for only two years.

This print is from the album issued by publisher Akiyama Buemon shortly after Yoshitoshi's death and retains its original album backing.

The Story Depicted in the Print as Told by John Stevenson

Source: Yoshitoshi's One Hundred Aspects of the Moon, John Stevenson, Hotei Publishing, Netherlands 2001.90.

Kazan temple moon

Kazanji no tsuki

In the year 985 the seventeen-year-old Kazan succeeded his uncle as emperor. After he had reigned for less than two years, his favorite consort died, leaving him profoundly distressed. While he was in mourning, he was tricked by an ambitious Fujiwara politician called Kaneie into taking the vows of a priest. This obliged him to abdicate. He retired to the Gangyō temple, which was later renamed after him, and died there in 1008 at the age of forty-one.

Such an early abdication was not unusual. An ex-emperor would often retire to one of the great monasteries, where the abbots, sometimes the younger sons of emperors themselves, were political powers in their own right. Often an ex-emperor continued to exert a degree of influence behind the scenes, but during much of Japanese history the emperor was a figurehead, with real power exercised by the great noble families. In Kazan’s time the administration of Japan was controlled by the Fujiwara family, which maintained its influence through a policy of intermarriage with the imperial family. The attempts of the fourteenth-century emperor Go-Daigo to rule as well as reign were unusual, and ultimately a failure. Go-Daigo chose Kazan temple for his residence after he was defeated by the Ashikaga clan in 1336. The temple buildings were destroyed in 1467 during the Ōnin War, which devastated most of Kyoto.

Fujiwara no Kaneie realized at the beginning of Kazan’s reign that the emperor was inconveniently independent and might be difficult to manipulate. While Kazan was distraught over the loss of his consort, Kaneie sent his son, Michikane, to the palace, where he gave a long and emotional speech about the transience of human life. Ending with the announcement that he intended to become a priest, he invited Kazan to join him. The impulsive young emperor agreed.

Before dawn, Michikane and Kazan went to take their vows at the Gangyō temple, which was located on the hills outside Kyoto. Kazan believed that they were going there secretly. The twelfth-century history Ōkagami states that it was the twenty-second day of the sixth month, when the moon was brightest around dawn, and that since it was so bright Kazan hesitated, afraid of being discovered. Michikane encouraged him to continue, but said that he himself had to return to Kyoto to see his parents for the last time – he had, of course, never intended to go through with the ceremony. As Michikane left, clouds suddenly obscured the moon, and Kazan hurried off through the darkness. He became a priest, and lost his sovereignty.

Ten years later Kazan was again used as a pawn by the Fujiwara family. He had never settled down to religious life and was having an affair with one of three sisters. Kaneie’s third son, Michinaga, arranged a confrontation one night between Kazan and Korechika, a political rival of Michinaga’s who was romantically involved with another of the sisters. Believing that he and Kazan were visiting the same mistress, Korechika shot at the ex-emperor in the darkness. The arrow grazed Kazan’s sleeve. Korechika was disgraced by the scandal, which at the same time brought no credit to Kazan.

In this design the unhappy young man walks through the grounds of the temple with a single loyal retainer. The eboshi, black lacquered caps, of both figures indicate their rank. The colors are somber, echoing the mood of the print. A delicate black-on-black pattern is a luxurious addition to Kazan's robe.

The brushwork of the trees and bushes in the moonlight is excellent, as is its reproduction by Yoshitoshi’s engraver and printer. The bushes to the right have an almost explosive energy, in keeping with the retainer’s dedication to this master. The regal cryptomeria that rises by the young man is a fitting symbol for an emperor. As usual, Yoshitoshi’s choice of detail in this print is impeccable.

This print employs the printing technique of shomen-zuri on the black robe. Literally meaning "front-printing", shomen-zuri is a polishing technique that was used to produce a shiny surface on black areas of some prints, often in intricate patterns. To produce this, a carved block was placed behind the print and the printed surface rubbed with a hard polisher, usually a boar’s tooth. (Mention is also made of use of porcelain and spoons, during the Meiji period, to achieve this effect).

Kazanji no tsuki

In the year 985 the seventeen-year-old Kazan succeeded his uncle as emperor. After he had reigned for less than two years, his favorite consort died, leaving him profoundly distressed. While he was in mourning, he was tricked by an ambitious Fujiwara politician called Kaneie into taking the vows of a priest. This obliged him to abdicate. He retired to the Gangyō temple, which was later renamed after him, and died there in 1008 at the age of forty-one.

Such an early abdication was not unusual. An ex-emperor would often retire to one of the great monasteries, where the abbots, sometimes the younger sons of emperors themselves, were political powers in their own right. Often an ex-emperor continued to exert a degree of influence behind the scenes, but during much of Japanese history the emperor was a figurehead, with real power exercised by the great noble families. In Kazan’s time the administration of Japan was controlled by the Fujiwara family, which maintained its influence through a policy of intermarriage with the imperial family. The attempts of the fourteenth-century emperor Go-Daigo to rule as well as reign were unusual, and ultimately a failure. Go-Daigo chose Kazan temple for his residence after he was defeated by the Ashikaga clan in 1336. The temple buildings were destroyed in 1467 during the Ōnin War, which devastated most of Kyoto.

Fujiwara no Kaneie realized at the beginning of Kazan’s reign that the emperor was inconveniently independent and might be difficult to manipulate. While Kazan was distraught over the loss of his consort, Kaneie sent his son, Michikane, to the palace, where he gave a long and emotional speech about the transience of human life. Ending with the announcement that he intended to become a priest, he invited Kazan to join him. The impulsive young emperor agreed.

Before dawn, Michikane and Kazan went to take their vows at the Gangyō temple, which was located on the hills outside Kyoto. Kazan believed that they were going there secretly. The twelfth-century history Ōkagami states that it was the twenty-second day of the sixth month, when the moon was brightest around dawn, and that since it was so bright Kazan hesitated, afraid of being discovered. Michikane encouraged him to continue, but said that he himself had to return to Kyoto to see his parents for the last time – he had, of course, never intended to go through with the ceremony. As Michikane left, clouds suddenly obscured the moon, and Kazan hurried off through the darkness. He became a priest, and lost his sovereignty.

Ten years later Kazan was again used as a pawn by the Fujiwara family. He had never settled down to religious life and was having an affair with one of three sisters. Kaneie’s third son, Michinaga, arranged a confrontation one night between Kazan and Korechika, a political rival of Michinaga’s who was romantically involved with another of the sisters. Believing that he and Kazan were visiting the same mistress, Korechika shot at the ex-emperor in the darkness. The arrow grazed Kazan’s sleeve. Korechika was disgraced by the scandal, which at the same time brought no credit to Kazan.

In this design the unhappy young man walks through the grounds of the temple with a single loyal retainer. The eboshi, black lacquered caps, of both figures indicate their rank. The colors are somber, echoing the mood of the print. A delicate black-on-black pattern is a luxurious addition to Kazan's robe.

The brushwork of the trees and bushes in the moonlight is excellent, as is its reproduction by Yoshitoshi’s engraver and printer. The bushes to the right have an almost explosive energy, in keeping with the retainer’s dedication to this master. The regal cryptomeria that rises by the young man is a fitting symbol for an emperor. As usual, Yoshitoshi’s choice of detail in this print is impeccable.

Shomen-zuri Printing Technique

Source: J. Noel Chiappa's website http://mercury.lcs.mit.edu/~jnc/prints/glossary.html

This print employs the printing technique of shomen-zuri on the black robe. Literally meaning "front-printing", shomen-zuri is a polishing technique that was used to produce a shiny surface on black areas of some prints, often in intricate patterns. To produce this, a carved block was placed behind the print and the printed surface rubbed with a hard polisher, usually a boar’s tooth. (Mention is also made of use of porcelain and spoons, during the Meiji period, to achieve this effect).

About the Series "One Hundred Aspects of the Moon"For details about this series which consists of one hundred prints with the moon as a unifying motif, see the article on this site Yoshitoshi, One Hundred Aspects of the Moon.

Print Details

| IHL Catalog | #113 |

| Title | Kazan Temple Moon (Kazanji no tsuki 花山寺の月) |

| Series | One Hundred Aspects of the Moon (Tsuki hyaku sugata つきの百姿) |

| John Stevens Reference No.* | 90 |

| Artist | Tsukioka Yoshitoshi (1839-1892) |

| Signature | Yoshitoshi 芳年 |

| Seal |  |

| Date | December 20, 1890 (明治廿三年十二月廿日印刷) |

| Edition | A single sheet issue, not bound into an album. |

| Publisher | Akiyama Buemon (秋山武右エ門) [Marks: seal 26-132; pub. ref. 005] |

| Carver | Yamamoto carver (Yamamoto tō 山本刀) |

| Impression | excellent |

| Colors | excellent |

| Condition | excellent - not backed (original state); almost full margins; small 3/4" piece of paper tape top margin verso. |

| Genre | ukiyo-e |

| Miscellaneous | |

| Format | oban |

| H x W Paper | 13 7/8 x 9 1/2 in. (34.9 x 24.8 cm) |

| H x W Image | 13 x 8 7/8 in. (32.7 x 22.2 cm) |

| Collections This Print | New York Public Library Humanities and SocialSciences Library / Spencer Collection; Minneapolis Institute of theArts 2002.161.1; Yale University Art Gallery 2011.143.1.90; The Tsubouchi Memorial Theatre Museum of Waseda University 201-4496; Ritsumeikan University ARC NDL-541-00-008 and NDL-223-00-00; Digital Collections of Keio University Libraries; Waseda University Cultural Resource Database 201-1777 |

| Reference Literature | * Yoshitoshi’s One Hundred Aspects of the Moon, John Stevenson, Hotei Publishing, Netherlands 2001 |

3/21/2020