About This Print

The Story Depicted in the Print as Told by John Stevenson

Source: Yoshitoshi's One Hundred Aspects of the Moon, John Stevenson, Hotei Publishing, Netherlands 200155.

The full moon

coming with a challenge

to flaunt its beautiful brow – Fukami Jikyū

meigetsu ya

kite miyo gashi no

hitai giwa - Fukami Jikyū

Afterthe establishment of the Tokugawa rule in 1600 ended the long anddestructive civil wars of the sixteenth century, martial skills becamesuperfluous. Samurai who did not become bureaucrats often foundthemselves unemployed, and the class as a whole was graduallyimpoverished. At the same time, the social and economic standing ofthe merchant and artisan classes quickly improved. Yet the samurairetained many privileges, and a merchant had little recourse against asamurai who cheated or ill-treated him. Young men in the towns formedgroups of otokodate, “chivalrous men,” who dedicated themselves torighting abuses and upholding what they saw to be justice. Theyachieved a semi-official status when they were recruited to accompanythe journeys of provincial lords to and from Edo. They even had theirown mon, or crests, like samurai.

In fact these groups oftenbecame no more than an excuse for excessive behavior. Colorfulcharacters would swagger around, showing off their fine clothes andpicking fights. They wore one sword instead of the samurai’s two, andoften carried a flute to indicate their artistic talents. In Kabukiplays they are invariably the sons of samurai who have given up theirprivileges in order to defend the oppressed. Many became folk heroes. Notorious gangs were formed, which were eventually disbanded byTsunayoshi, shogun from 1680 to 1709. The yakuza of today’s Japan aretheir spiritual descendants.

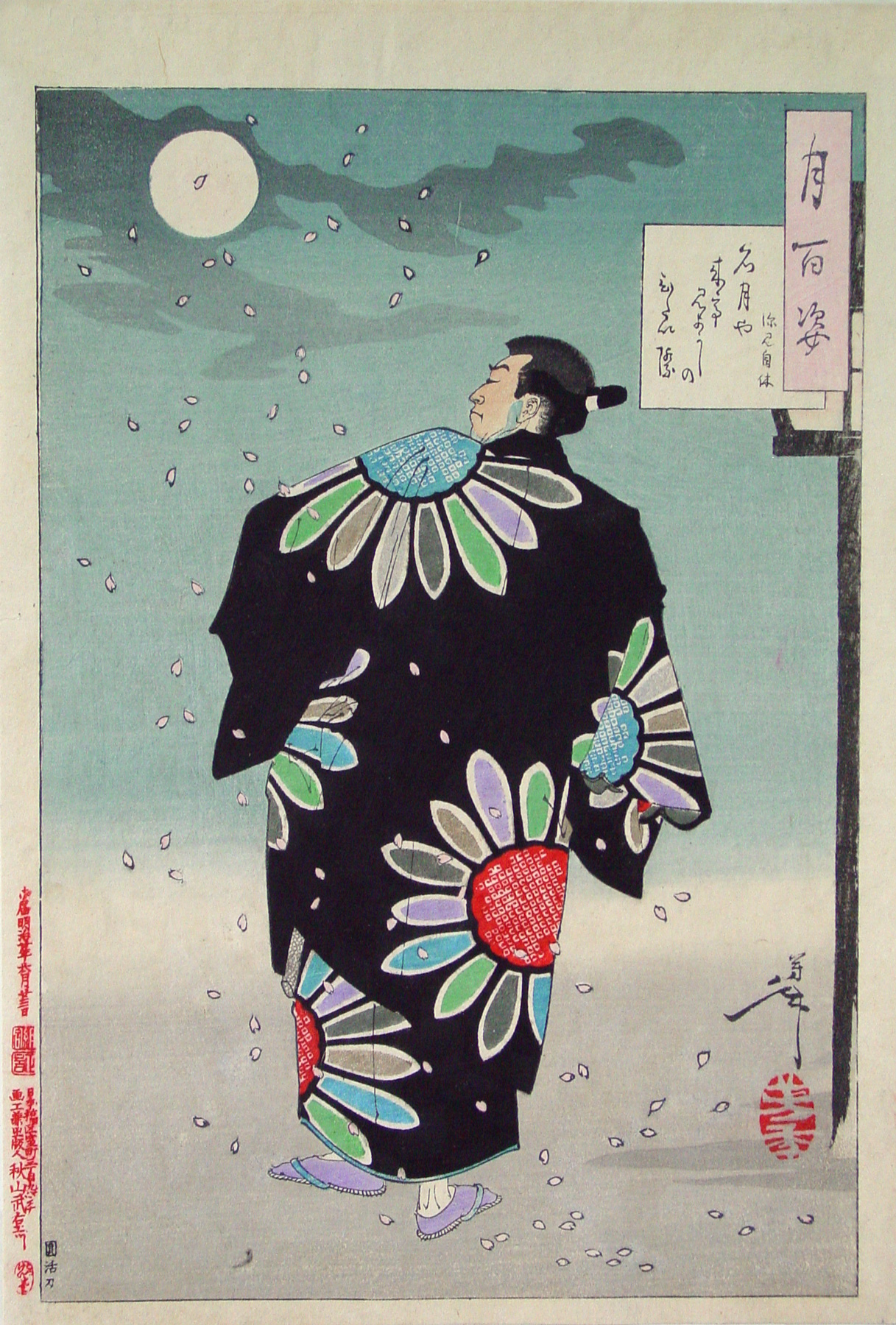

In this print a young otokodate,identified in the cartouche as Fukami Jikyū, walks jauntily down thestreet. He wears a black kimono with a huge chrysanthemum pattern,made even more magnificent in the original by black-on-blackburnishing. It is just the sort of robe that a dandy would wear in aKabuki play, and the print has a strong Kabuki flavor.

Jikyu’sbearing brilliantly suggests his boldness and pride. The printradiates with confidence, from the young man’s square shoulders to thepetal placed in the very center of the moon. It is spring, cherrytrees are in bloom, and the moon is full, an exhilarating combination. Falling petals and the distinctive street lantern to Jikyū’s rightindicate that the scene is set in the Yoshiwara pleasure district withits famous cherry trees. The young man looks up to receive themoonlight on his face and composes a poem which implies that he isquite as beautiful as the full moon.

Fukami Jikyū was thegrandson of a general who served the Fukushima, a family suppressedunder the Tokugawa shogunate. He was originally known as FukamizoSadakuni Jūzaemon. In 1681 the historical Jūzaemon, rather older thanthe man in the print, was arrested for gang activities – he was sofeared that whole division of police was sent to bring him in. At hishearing, he stated that he was a samurai and demanded to know why hehad been arrested like a common criminal. He then refused to answerquestions, and was exiled for thirty years. When he returned to Edo,aged eighty, he became a priest and took the name Fukami Jikyū. Stillrobust, he lived for another ten years.

Source: The Beauty & The Actor, Ukiyo-e: Japanese Prints from the Rijksmuseum Amsterdam and the Rijksmuseum voor Volkenkunde, Leiden, Matthi Forrer, C. v. Rappard-Boon, Hotei Publishing, Amsterdam / Leiden, 1995, p. 191

Fukamai Jikyū was a seventeenth-century otokodate. An otokodate ("chivalrous commoner") took it upon him to defend the interests of the poor and oppressed. They were celebrated figures in novels and they figure prominently as heroes in kabuki plays, often in opposition to villains. In these plays, they are often the sons of samurai who have renounced their status in order to defend the interests of the poor. In keeping with their showy characters they wear spectacular kimono, and are skilled and courageous fighters. Although in theory the otokodate were meant to defend the needs of the poor and oppressed, in reality, the border-line between these otokodate bands and petty criminals was at times very vague. In this composition, Yoshitoshi reverts to the old tradition in kabuki prints of depicting the human subject in full-length against an empty background. However, in this print a few but nevertheless very important elements are included: the moon, a burning lantern and falling cherry petals. Together these elements create the feel of a quiet and peaceful spring evening, against which the heroic figure in his splendid kimono stands in sharp contrast.

The poem in the cartouche reads:

The famous moon, well,but watch

my forehead

meigetsu ya

kite miyo kashi no

hitaigiwa

Jikyū was known for his high forehead as well as for his golden teeth. He shares this first feature with one of the characters from the kabuki play Sukeroku, who was in fact based on him. The first Sukeroku play was written in 1713 for Ichikawa Danjuro II at a time when Fukami Jikyū was in exile on the island of Oki.

Image from Publisher's Bound Album (Issued shortly after Yoshitoshi's death)

About the Series "One Hundred Aspects of the Moon"For details about this series which consists of one hundred prints with the moon as a unifying motif, see the article on this site Yoshitoshi, One Hundred Aspects of the Moon.

Print Details

| IHL Catalog | #43 |

| Title | Thefull moon coming with a challenge to flaunt its beautiful brow – FukamiJikyū (Meigetsu ya kite miyo gashi no hitai givwa - Fukami Jikyū 深見自休) |

| Series | One Hundred Aspects of the Moon (Tsuki hyaku sugata 月百姿) |

| John Stevens Reference No.* | 55 |

| Artist | Tsukioka Yoshitoshi (1839-1892) |

| Signature | Yoshitoshi 芳年 |

| Seal | Yoshitoshi 芳年 |

| Date | June 23, 1887 (御届明治廿年六月廿三日) |

| Edition | Likely from the album issued by publisher Akiyama Buemon shortly after Yoshitoshi's death |

| Publisher | Akiyama Buemon (秋山武右エ門) [Marks: seal 26-132; pub. ref. 005] |

| Carver | Enkatsu tō 円活刀[full name Enkatsu Noguchi] |

| Impression | excellent |

| Colors | excellent |

| Condition | excellent - Japanese album backing paper; very minor marks and flaws |

| Genre | ukiyo-e |

| Miscellaneous | Fukami, a young man in full bloom, made a poem implying he was as beautiful as the full moon. |

| Format | oban |

| H x W Paper | 14 1/8 x 9 5/8 in. (33.9 x 24.4 cm) |

| H x W Image | 12 7/8 x 8 3/4 in. (32.7 x 22.2 cm) |

| Collections This Print | TheBritish Museum 1906,1220,0.1439; The New York Public Library Humanitiesand Social Sciences Library / Spencer Collection Digital ID:1269829; Yale University Art Gallery 2011.143.1.55; Hagi Uragami Museum (Yamaguchi, Japan) UO1552; Tokyo Metropolitan Library 加4722-29; The Tsubouchi Memorial Theatre Museum of Waseda University 201-4451; Ritsumeikan University ARC NDL-541-00-032 |

| Reference Literature | * Yoshitoshi’s One Hundred Aspects of the Moon, John Stevenson, Hotei Publishing, Netherlands 2001, pl. 55; The Beauty & The Actor, Ukiyo-e: Japanese Prints from the Rijksmuseum Amsterdam and the Rijksmuseum voor Volkenkunde, Leiden, Matthi Forrer, C. v. Rappard-Boon, Hotei Publishing, Amsterdam / Leiden, 1995, p. 147, pl. 156 |