THE RISE OF MACEDONIA

"Both sides claimed the victory [at Mantinea, 362], but it cannot be said that with regard to the acquisition of new territory or cities, or power either side was better off after the battle than before it. In fact there was even more uncertainty and confusion in Greece after the battle than there had been previously." Xenophon, VII 5.26

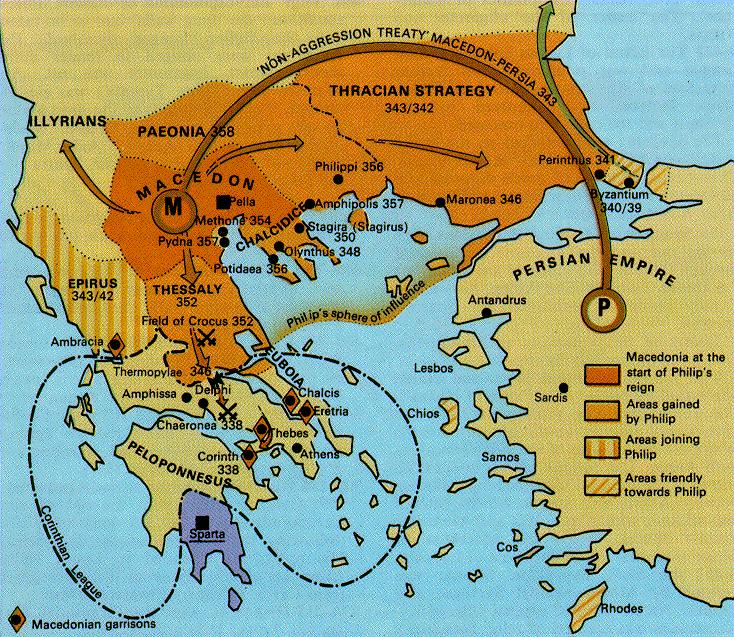

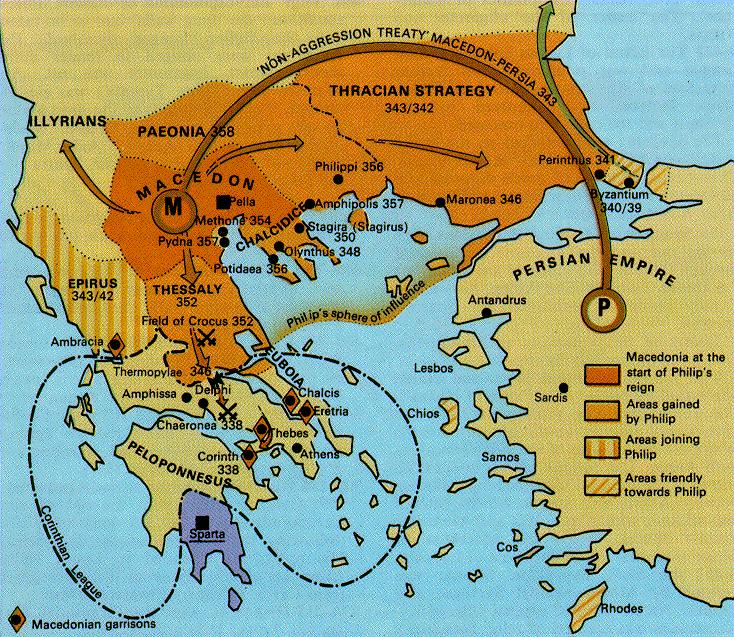

What follows here is an outline of Macedonia's rise. To understand the process by which in the course of 25 years (between the battles of Mantinea and Chaeronea, 338 BC), one must understand the following circumstances:

- The 'imperial' states no longer had the resources (human and fiscal) or the will/ leadership qualities to contest for hegemony. Note the theorika below.

- To deal with revolts within the Persian Empire, the Great King was hiring an increasingly large number of Greek mercenaries, and was no longer as able/ as ready to subsidize instability in Greece. (But why should he? Self-flagellation among the Greek states was endemic.)

- Macedonia had long had the resources (gold and silver mines; timber; population) to become a major player in the Aegean world. What was missing was a national unity and identity (such as had come into being in the Greek city states) or a charismatic leader of energy and insight to harness the potential. With the accession of Philip, the latter was granted.

- The Emergence of Macedonia as a "Great Power"

- Geography: lower Macedonia has good agricultural land and a flat coast; upper Macedonia is predominantly pastoral and mountainous. Both, however, have "continental" or "Balkan" climates that are wetter and colder than the Mediterranean. Though there is a continuous mountain barrier, there are clear invasion routes from both the west and the north. Maedonia was vulnerable to barbarian attacks from north, northwest, and northeast, and to the Greeks in the south.

- Population: The proportions and numbers were probably similar in the 4th C. Macedonians were a racially mixed group: the lower orders belonging to the old Bronze Age population, the aristocracy to the Dorian invaders [cf.Sparta]. The Macedonians considered themselves to be a unique folk with an independent government. The Athenians considered even the aristocrats to be uncultivated: one was not considered a "man" until, for example, he had killed a bear by himself.

- Government:

- on the "heroic" or "Homeric" model. The kingship was hereditary in one family (the Argead House) but was elective by 'nation in arms'. The king himself was the leading warrior, owner of all land, supreme judge, supreme commander, high priest and the personification of the state. The bonds between ruler and ruled were all based on personal, mutual service. Macedonian kingship was essentially charismatic and unstable; that is, there was no institutional structure for succession, diplomacy, administration of justice. Hence violence / assassination/ blood feud mark the transition form one king to another.

- Aristocracy: the nobles from each tribe. Comparable in values and behavior to the "princes" of the Iliad; that is, they could be controlled only marginally by the king. The members of the nobility were the "companions" of the king and, in manner of dress and speech, his approximate equals. Resembles the situation in many Greek cities in the 8th and 7th centuries, and in the feudal states of Europe before 1000.

- Cities: developed in the lowlands, but were not "city- states" in that they ever had autonomy; rather, they were royal administrative centers. This structure will be significant in the Hellenistic period, for Alexander and his successors adapted the Macedonian model to rule the ANE, and not the polis model.

- The Macedonian "identity" was created out of pressure from the Balkans and from Greek expansion on the coast.

- Early history is characterized by periodic invasions from the Balkans (Macedonia often had to pay the Illyrians "tribute"), by intense dynastic competition (the extermination of all the mature males in the royal house was a regular feature of royal life, mitigated only by the polygamy allowed the king as indeed viking 'kings' also practiced) = diplomacy through marriage and common children. In so far as the Greeks were concerned and they are the ones who wrote history), the early kings were notoriously inconstant and treacherous, making and breaking treaties in a completely unacceptable manner by [their own concept of] international standards.

- The most important early king was Archelaus (413-399), who, because he changed sides so often, incensed both Spartans and Athenians...in his defense, he had little choice, but to act in the best interests of himself and Macedonia. He was, however, the first to create an army on the Greek model (as distinct from the Homeric mob plus warrior king). This suggests that Macedonia was beginning to enjoy the material conditions that had made possible the hoplite revolution. He was the first to built forts and construct roads both of which stabilized Macedonian life. In his reign, Macedonia begins to expand along the Aegean coast. To "civilize" his aristocracy, he imported Greek teachers and intellectual figures. Euripides wrote his last play, the Bacchae, at his court

- Alexander (369-8) formed the "foot companions" / alternative, the elite of the Macedonians infantry. He sought and won the good will of Thebes, then at the height of its power, and sent as a token of good faith, his nephew, Philip, to be held as a hostage/trainee (in this position, Philip mastered the new tactics and strategies developed by the Thebans).

- THE RISE OF PHILIP:

- Elected regent in 359, but faced with the usual problems. Note that each change of power offers these elements new opportunities.

- His three half-brothers were rivals, potential and actual not only to the regency, but for the kingship. Moreover, the nobles always seek to secure their own independence from the crown.

- Balkan invaders, Paeonians and Illyrians, who had been checked only by paying tribute, now ravage western and northern Macedonia.

- The Chalcidian League (Greek city-states to the east , and nows re-constituted since Sparta had dismantled it in the 380's)

- Trained and experienced in the intricacies of dynastic struggles, Greek culture and diplomacy and possessed of sound judgment and energy, Philip immediately achieved some notable successes employing methods he would use regularly thereafter:

- dynastic politics: kept enemies divided by marriage alliances (it helps to be a polygamist!) and by "grants" (some may call this bribery) to both individuals and states which might undermine his leading enemies; such actions bought him time, and divided his enemies.

- clear recognition of strategic and tactical possibilities and a willingness to change his goals to maximize his opportunities --strategy of the indirect approach.

- rapid deployment on inner lines. His enemies regularly arrive too late.

- use of Pavlovian diplomatic techniques; to induce paranoia through 'fear conditioning' or by giving mixed signals.

- In victory he was always moderate

- MACEDON GAINS CONTROL OF THE GREEK STATES

- The diplomatic struggle.

- Isocrates, one of the great Greek teachers of rhetoric, publishes his Philippus in 346, urging Philip to unite the Greeks, establish homonoia (internal tranquility) and then attack Persia (and, thereby, get all those troublesome mercenaries out of Greece). <consider the role of Pope Urban II in urging the Crusades in 1095>. Athens ought to set aside her demagogues who urge the re-establishment of the Athenian League; her true interests are those of peaceful trade.

- Demosthenes, the greatest of Athenian orators and one of the leading politicians of his day, opposes this argument, noting that Philip is a danger to Greek "freedom and autonomy".

- The theorika: state allowances for poor people to go to theater, etc. After the Peloponnesian War: all state surpluses should be used for theorika except during wartime...another law punished by death<!!> anyone who suggesting using the funds for military purposes during peace time.

- Macedonia becomes more powerful, more unified and wealthier than ever before.

- Philip has begun to develop new mines in Thrace.

- Scientific methods of agriculture and breeding are introduced.

- Moreover, Philip now controls the Balkans through modern Albania in the west and up to the Sea of Marmara (Hellespont) in the east. In this expansion, he threatened Corinth's domination of the western trade and Athens' control of the Aegean.

- Partly for internal reasons (the instability of the democracy) and partly due to Philip's bribery (hardly any Athenian politician escapes this accusation), the Athenians repeatedly fail to defend their interests in the north Aegean. Note that Philip replaces the Persian king as the corrupter of Greek politicians.

- The choice is widely discussed in Greece. Philip did not claim that he wished to conquer Greece, but, rather he openly sought an alliance with himself as the hegemon (or "leader"). In return he would help to secure the peace and lead a campaign against Persia. Should one accept the offer or fight to retain freedom? The Athenians, under the guidance of Demosthenes, resolve to oppose. It should be noted that the Athenians were anxious about their own 'freedom and autonomy', but lacked the will and the means (material and human resources) to oppose effectively.

- In 339, Philip is threatening the key cities of Perinthus and Byzantium without formally violating a peace treaty with Athens but Athenians are involved in the defense of those cities, contributing both money and men. The Athenians and other states are mostly concerned about the consequences of Philip, or anyone else, gaining control of the straits from and to the Black Sea. The access to grain and dried fish is too important to be left in the hands of another power.

- The immediate event which precipitated the open war was a minor confrontation in Central Greece which brought Thebes and Athens into alliance against Locris (a minor state) and her champion Philip. The latter, acting more quickly than expected, gained control of the routes into Central Greece

- The Battle of Chaeronea, August, 338.

- the two sides were roughly even in size, 30,000 infantry and 2,000 in cavalry.

- Philip had already completed the reform of his army. In particular, he took the deep formation from the Thebans, but placed the individuals somewhat more loosely (at three- foot intervals), making his phalanx more flexible, and then devoted particular attention to the training in weapons including a longer spear. Moreover, the phalanx was not designed to attack or to defend in the traditional Greek manner, but to hold and exhaust the line of the opponents until the heavy cavalry, attacking in wedges on the flanks, could overwhelm the enemy.

- Philip attacked obliquely, engaging the Thebans and the Sacred Band first, crushing it (the latter died to a man; Philip, who must have known many in the Band from his days in Thebes, wept about the loss), and then rolling up the rest of the line. Philip's right flank retreated strategically.

- Alexander distinguished himself in this battle leading the decisive cavalry charge.

- The aftermath

- Toward Athens, Philip was remarkably generous --suggesting how much weight Philip attached to public opinion at Athens. No Macedonian was to be stationed in Attica. The Athenians were to become the allies of Macedonia and dissolve their maritime alliance.

- Toward the rest of Greece, Philip assigned garrisons to the key cities of Corinth, Chalcis, Ambracia and Thebes. The latter, in particular, he treated harshly, by dissolving the Boiotian League and confiscating the property of his enemies.

- League of Corinth --most Greek states compelled to join.

These provisions say much about what was wrong with the imperial 'wanna-bes' among the Greek cities.

- Observe general peace and act together for collective security.

- Respect 'freedom and autonomy' of each member under own constitution.

- Refrain from executions, re-distribution of property and other subversive measures.

- Creation of executive council with powers of war/peace, taxation, justice and arbitration. States participate in proportion to naval and military contributions.

- Philip appointed hegemon for war against Persia.

- The league did not fulfill the hopes of Isocrates or Philip. Unity depended totally on Philip's dominant position; no real 'reconciliation', rather the older forces, though now more hidden, continued beneath the surface.

- THE END OF PHILIP

- An army, under Parmenio, was sent into "Asia" (Turkey) to gain a foothold and prepare for the arrival of the main force under Philip (spring, 336).

- Even though Olympias, the mother of Alexander, was the official queen, Philip had married six times and had many mistresses. When he fell in love with Cleopatra (no, not Liz Taylor) he had a problem: she was too highly borne to be anything but his queen. Olympias was then divorced and the status of Alexander became uncertain.

- In the summer of 336, Philip was assassinated by a nobleman to whom Philip had not given justice. It has been suggested by both ancient and modern writers that he [Alexander] or most likely his mother was responsible for the deed [and Freud loved it!]. Whatever the truth, it is well to remember that Philip's two leading generals, Parmenio and Antipater (both of whom were in a position to do something about it) accepted Alexander's claim of innocence, but then again they understood Macedonian tradition.

- It is difficult to assess Philip correctly. His son clearly surpassed him, Demosthenes, his enemy, misrepresents his intentions and achievements and we have no alternative to that account. Still, Alexander would have gone nowhere had not Philip created the means (the army) and the system of government (really the first national state in European history) which Macedonia had in 336.

- It is said that "Greek liberty perished on the field of Chaeroneia".

- True?

Yes, in the sense that the Greek states, Athens and Thebes included, did submit to Philip and to Macedonia and that the surrender was complete. They may have preserved their ancestral constitutions [autonomy], but it was an indulgence; and they were not 'free' in the sense that they had independence in foreign policy or finance. It is also true that the Greek states would never again be in a position to assert their liberty.

- In another sense it is false. Athens, Sparta and Thebes had all tried to dominate Greek states and, for a period, each had succeeded. that is 'freedom and autonomy' were available, as in the days of Achilles and Hector, only to those who could assert it with a spear.

- Too many atrocities had been committed in the name of "freedom". Had the Greek states had sufficient resources and greater statesmanship, they might have brought about a more enduring nation.

- The Greek polis had, on the whole, been a very successful experiment in communal life. It was limited especially by the perception of membership in the civic body (everyone must know everyone else; only by this means could behavior be controlled) and because it its very success had ultimately led to a kind of inflexibility. Indeed the very success of very success of the polis as a result of inclusion and compromise, may paradoxically have been the reason why the Greek poleis were not ready to extend the same courtesies to the fellow Greek states.