Late

Medieval Canon Law on Marriage Late

Medieval Canon Law on Marriage

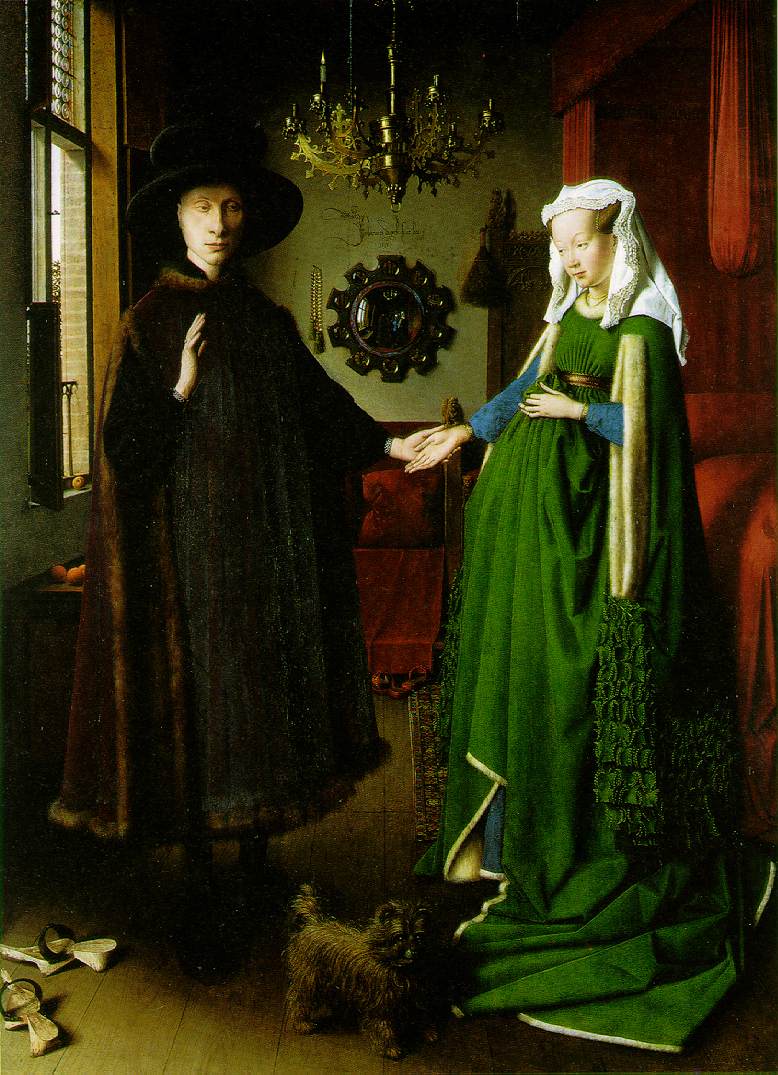

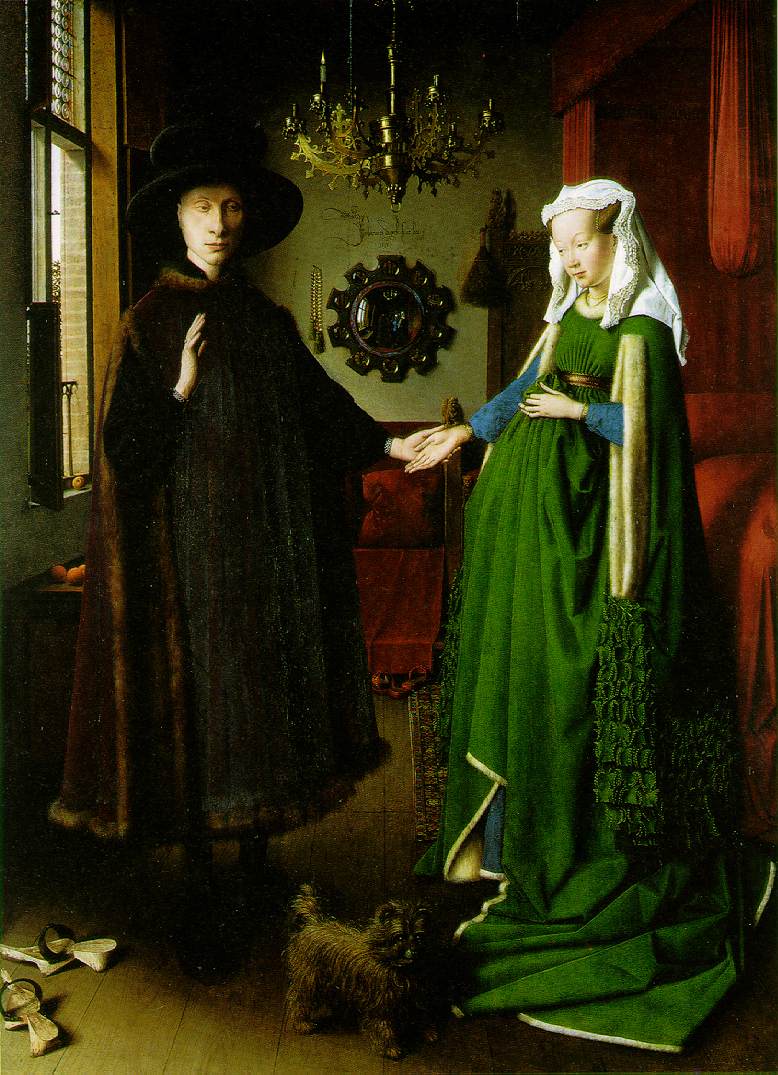

Image: The

Arnolfini Marriage

(1434), by Jan van Eyck (c. 1395-c. 1441). Image

source: WebMuseum

of Art

The foundations of

church law on marriage were laid during the eleventh

and twelfth centuries, the period of the Gregorian Reforms. These can

be

summarized briefly:

- With regard to marriage and divorce, the legislation of the

eleventh and

twelfth centuries implanted firmly the doctrine of marital

indissolubility;

the only permissible grounds for divorce and remarriage were impotence,

incest (i.e., marriage within the forbidden degrees of consanguinity

and

affinity), and adultery. This threatened to end the widespread practice

of divorce; it also encouraged the church to assert its judicial

authority

over marriage law; and it diminished the ability of family and kin to

control

marriage independently.

- With respect to incest, the forbidden degrees

of consanguinity

and affinity remained high. In 1059, Pope Nicholas II issued an

encyclical

which required that "if anyone had taken a spouse within the seventh

degree,

he will be forced canonically by his bishop to send her away; if he

refuses,

he will be excommunicated." In 1215, the Fourth Lateran

Council reduced the number of prohibited degrees from seven to

four.

Still, the cummulative effect was to encourage exogamy--i.e.,

marriage

outside one's native community--and the growth of regional marriage

markets.

- The reforms codified a trend toward monogamy,

already well under

way by the turn of the millenium, which supplanted earlier forms of

polygynous

marriage and concubinage, such as Friedelehen (a kind of

second-class

marriage).

- The canonists also asserted authority over the sexual

practices of laypeople:

the reform-era legislation was generally milder than earlier

regulations,

but continued to uphold the notion that sex for any purpose other than

procreation within marriage was sinful. All nonmarital sex was

condemned

as criminal; all homosexual intercourse was forbidden.

- Finally, the reform legislation reinforced and implemented

long-standing

prohibitions

against clerical marriage and concubinage.

|

It

is unclear how consistently the provisions on forbidden degrees of

incest

were enforced; considerable controversy centered on the reckoning of

degrees

of kinship, for which there were two systems in operation, the Roman

and

the far stricter Germanic scheme. Under the Roman scheme, degrees of

kinship

were calculated by counting the number of acts of generation separating

ego and other. Siblings, under this system, were separated by two

degrees

of kinship, one for the act of generation between the first sibling

from

her parents, another for the act of generation between the parents and

the second child. Similarly, an uncle and niece are separated in the

third

degree.

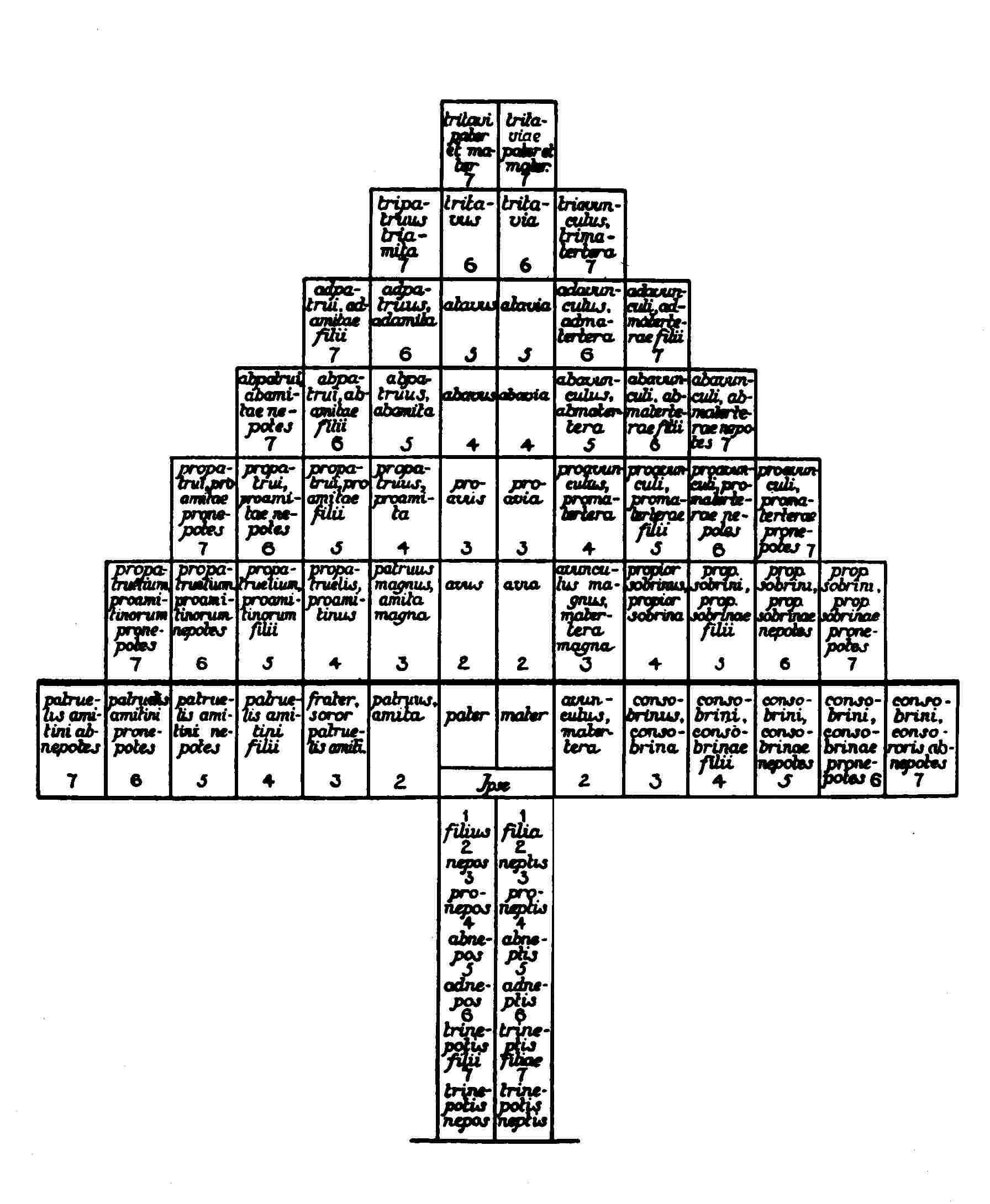

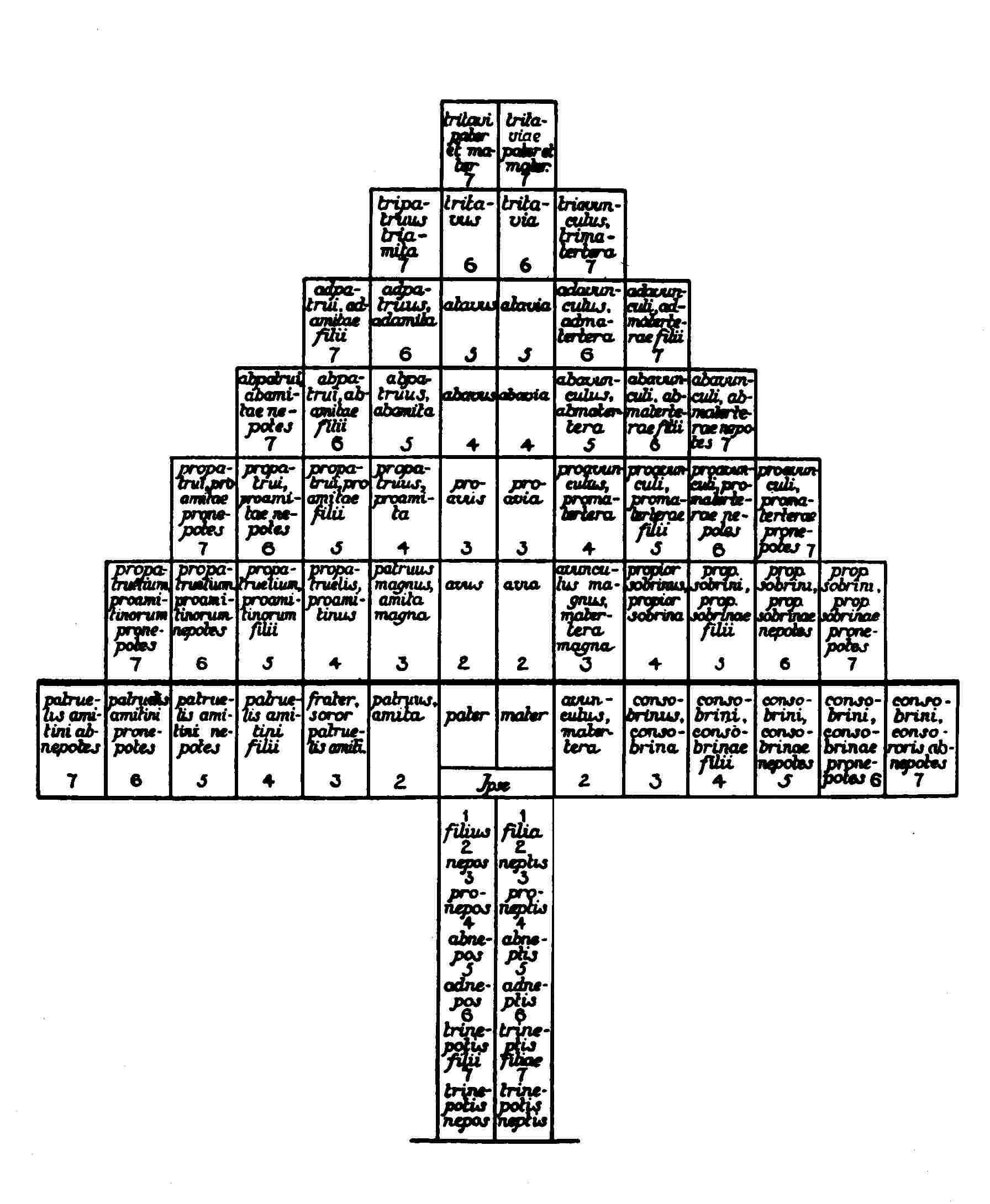

Image right:

the "Germanic" system for calculating degrees

of separation, adapted from Isidore of Seville (Etymologarium sive

Originum,

ed. W.M. Lindsay, Oxford, 1911); in Jack Goody, The Development of

the

Family and Marriage in Europe (Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press,

1983), 143.

According to the Germanic

calculation, degrees of kinship were based

on the unity of the sibling group, all of whom were related in the

first

degree, so that all brothers and sisters of a single marital couple

were

related to each other in the first degree. By this system of reckoning

from a hypothetical "ego" (ipse on the chart), seven degrees of

separation included all descendents from a pair of common

great-great-great-great-great-grandparents.

Under this system, the circle of kinship embraced all descendants of a

common great-grandfather, i.e., second-cousins.

Moreover, these provisions

left open the question of how a marriage

came into being. This matter was given much sharper definition in

Gratian's

Decretum

(ca. 1140). Gratian tended to regard marriage as a process with two

stages:

(a) in

initiation, the couple exchanged freely-consenting vows of

marriage, which created a spiritual union between them; in the (b) completion

or

perfection of the marriage, the couple created a physical union

by consummating their bond sexually. Both stages were necessary to

complete

a marriage: no sexual union constituted marriage without consent to

marry,

just as no marriage as wholly formed without sexual union. Indeed, for

Gratian it was sexual intercourse that transformed the union into a

"sacrament"

and made a marriage indissoluable. If marriage was situated between

three

kinds of union -- sexual, spiritual, and social -- Gratian's

Decretum

shifted definitions strongly toward the first of these. But not to the

neglect of consent: only a marriage freely entered was valid, if both

parties

were at least seven years old, both were Christian, and neither were

bound

by an oath of chastity.

With its emphases on the

necessity of consent

and on sex as a positive good, the High Medieval conceptualization of

marriage

represented a departure from the hostility and revulsion toward

sexuality

that characterized the writings of many earlier canonists. As it

developed

after Gratian, canon law also distinguished between two kinds of vows,

and weighed them differently depending on whether these vows had been

consummated

sexually.

1. “Present Vows” (sponsalia

per verba de praesenti)

Present vows were an exchange of promises in the present, for the

present,

between consenting male and female (i.e., "I, Margot, take you, Hannes,

to be my husband now and forever"). In general, these were thought to

constitute

a valid marriage, even if the vows were exchanged in secret and without

the consent of parents and kin.

-

If present vows were consummated, i.e, if they were sealed spiritually

through sex, they constituted a valid marriage and were therefore

indissoluble.

-

If present vows were left unconsummated, the union could still be

dissolved

only

if

-

(a) one of the two parties entered a monastery (i.e., took a higher

vow);

or

-

(b) the pope granted a dispensation from the requirements of canon law.

2. “Future Vows” (sponsalia

per verba de futuro)

Slightly more complicated

were future vows of marriage exchanged between

consenting parties (i.e., "I, Margot, promise to take you, Hannes, to

be

my husband at such-and-such a date"). Future vows were obligating, but

did not constitute an indissoluable marriage for the present. Therefore

future vows could be dissolved

- By mutual consent of the parties involved; or

-

If one of the two made present vows with somebody else (i.e.,

took

a higher vow); or

-

If one of the two moved to a foreign land; or

-

If one of the two had heterosexual intercourse with somebody else; or

-

If one of the two became a heretic or an apostate; or

-

If one of the two became a leper.

In this system, the

social dimension of marriage got short shrift: Gratian

was no enthusiast for clandestine marriage, but his emphasis on consent

and sexual consummation left little room for parental consent or the

need

for public, ceremonial marriage. Indeed, the emphasis on consent in

marriage

only grew stronger: Pope Alexander III (1159-1181) ruled that future

vows,

if they were given freely and consummated sexually, constituted an

indissoluable

marriage. Neither parental or kin-group consent, nor dowries, nor

publicity

were needed to complete a marital union.

At the same time, however,

canon law also insisted that marriages should

be

public and that parents should have a say in their creation. In

addition

to banning marriage within the fourth degree of consanguinity, the

Fourth

Lateran Council had also banned marriages concluded in secrecy. The

Council's

intent had been to provide an effective means of enforcing

consanguinity

laws: by making marriage public, incest impediments might come to light

more readily. The Council also intended to counteract a series of

problems that had arisen from a definition of marriage based on consent

and sex. In a court of law, for example, it was difficult to prove or

disprove

whether the parties to a marriage had exchanged vows consensually or

had

consummated the union freely. Public marriage had placing the consent

of

both parties on display and reinforcing it with the testimony of

witnesses.

Also, secret marriages had the potential to invalidate subsequent,

public

marriages and this, in turn, threatened the social functions of

marriage

as a tool of alliance-making and property transfer. As James A.

Brundage

notes,

The

upper classes sought to make their marriages

as public and as splendid as possible, not only as a matter of honor

and

social obligation, but also to assure that property transactions

connected

with the marriage would be honored.

From 1215 on, therefore,

canon law on marriage formed between the sometimes

contradictory requirements of consent and publicity, which may explain

the hesitance of theologians to affirm the sacramentality of marriage

unequivocally.

Albert the Great (c. 1200-1280) allowed it, but only because the

sacrament

helped married people achieve the goals of marriage (Brundage, 432).

Duns

Scotus (1270-1308) solved the problem by distinguishing two types of

marriage:

by itself, free mutual consent created a valid marriage, but only

a public, church ceremony could establish a sacramental marriage.

Others absorbed sacramentality into Gratian's two stages of marriage,

initiation

and completion. According to this view, a couple received one portion

of

the sacramental grace that marriage conferred in the first stage, when

they exchanged vows; they received the second portion, so to speak,

when

they consummated the union sexually. The view which ultimately

prevailed,

however, was that of Thomas Aquinas, who affirmed that marriage was a

sacrament

and that the exchange of consent itself conferred grace (Brundage,

433).

In 1215, the Fourth

Lateran Council made

the following rulings on incest and clandestine

marriage:

§50. On the

Restriction of Prohibitions to Matrimony

It should not be judged reprehensible if human decrees are sometimes

changed according to changing circumstances, especially when urgent

necessity

or evident advantage demands it, since God himself changed in the new

Testament

some of the things which he had commanded in the old Testament. Since

the

prohibitions against contracting marriage in the second and third

degree

of affinity, and against uniting the offspring of a second marriage

with

the kindred of the first husband, often lead to difficulty and

sometimes

endanger souls, we therefore, in order that when the prohibition ceases

the effect may also cease, revoke with the approval of this sacred

council

the constitutions published on this subject and we decree, by this

present

constitution, that henceforth contracting parties connected in these

ways

may freely be joined together. Moreover the

prohibition

against marriage shall not in future go beyond the fourth degree of

consanguinity

and of affinity, since the prohibition cannot now generally be

observed

to further degrees without grave harm. The number four agrees well with

the prohibition concerning bodily union about which the Apostle says,

that

the husband does not rule over his body, but the wife does; and the

wife

does not rule over her body, but the husband does; for there are four

humors

in the body, which is composed of the four elements. Although the

prohibition

of marriage is now restricted to the fourth degree, we wish the

prohibition

to be perpetual, notwithstanding earlier decrees on this subject issued

either by others or by us. If any persons dare to marry contrary to

this

prohibition, they shall not be protected by length of years, since the

passage of time does not diminish sin but increases it, and the longer

that faults hold the unfortunate soul in bondage the graver they are.

§51. Prohibition

of Clandestine Marriages

Since the prohibition against marriage in the three remotest degrees

has been revoked, we wish it to be strictly observed in the other

degrees.

Following in the

footsteps of our predecessors, we altogether

forbid clandestine marriages and we forbid any priest to presume

to be present at such a marriage. Extending the special custom of

certain regions to other regions generally, we decree

that when marriages are to be contracted they

shall

be publicly announced in the churches

by priests, with a suitable time being fixed

beforehand within which whoever wishes and is able to may adduce a

lawful

impediment. The priests themselves shall

also investigate whether there is any impediment. When there appears

a credible reason why the marriage should not be contracted, the

contract

shall be expressly

forbidden until there has been established from clear documents what

ought to be done in the matter. If any persons presume to enter into

clandestine

marriages of

this kind, or forbidden marriages within a prohibited degree, even

if done in ignorance, the offspring of the union shall be deemed

illegitimate

and shall have no help

from their parents' ignorance, since the parents in contracting the

marriage could be considered as not devoid of knowledge, or even as

affecters

of ignorance.

Likewise the offspring shall be deemed illegitimate if both parents

know of a legitimate impediment and yet dare to contract a marriage in

the presence of the

church, contrary to every prohibition. Moreover the parish priest who

refuses to forbid such unions, or even any member of the regular clergy

who dares to attend

them, shall be suspended from office for three years and shall be

punished

even more severely if the nature of the fault requires it. Those who

presume

to be united

in this way, even if it is within a permitted degree, are to be given

a suitable penance. Anybody who maliciously proposes an impediment, to

prevent a legitimate

marriage, will not escape the church's vengeance. (emphasis

added)

Return

to 441 Homepage

Late

Medieval Canon Law on Marriage

Late

Medieval Canon Law on Marriage