|

| Marine Team | University of Oregon | Environmental Studies Department |

|

|

SAFETY RULES FOR A TIDEPOOL TRIP There are lots of dangers of which you need to be aware of such as strong waves, drift logs, and slippery rocks that could hurt you if not careful. Please read the safety rules below to ensure an enjoyable trip. 1. Don’t turn your back on the ocean. Large sneaker waves could knock you over and pull you down. 3. Watch your step. The intertidal is full of loose rocks and slippery seaweed. Make sure to step carefully, stay low, and use your hands. Please, no running!

ETIQUETTE FOR A TIDEPOOL TRIP 1. Tide pools are home to many organisms. Therefore do not take anything out of the tide pools. If you pick up an organism, make sure to put it back exactly where you found it. How would you like it if someone took you away from your home and didn’t put you back? 2. Put rocks back if you flip them over. Organisms that live on the bottom or under a rock cannot live on the top of a rock and vice versa.

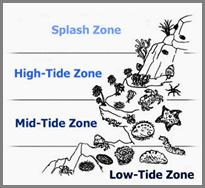

ENVIRONMENTAL CONDITIONS & ZONES OF THE ROCKY INTERTIDAL The rocky intertidal region (the area between the lowest and highest tide marks) is a harsh place. Environmental conditions such as incoming and outgoing tides, wave force, and air exposure change daily, requiring adaptations to this area. As the tide comes in-and-out, the intertidal region becomes divided into zones. The splash zone and high-tide

ADAPTATIONS OF ROCKY SHORE ANIMALS

The shape of organisms can also help an animal get from being torn from a rock by waves. Flat shapes (i.e. chitons, limpets, barnacles, and crabs), strong shells (i.e. snails, crabs, barnacles, and mussels), and flexibility (i.e. anemones and seaweeds) are a few of the adaptations that intertidal organisms use to survive. When exposed in air many organisms seal themselves (i.e. limpets and snails) or layer (i.e. seaweed) in order to keep water inside and have less surface area exposed.

DIVERSITY IN THE ROCKY INTERTIDAL

ORGANISM DESCRIPTIONS

There are many organisims to be discovered within an intertidal ecosystem. Listed here is information on the more commonly seen organisms. Click on the sidebar links or simply scroll down and enjoy these beauties. AGGREGATING ANEMONE (surf anemone, clonal anemone) Anthopleura elegantissima Size: up to 3” in diameter. Habitat: Found in colonies on rocks in the low to mid intertidal. Colonies prefer to settle in depressions or crevices of rocks, but can multiply to cover entire rock surfaces. Appearance: Aggregating anemones are attached to rocks by a pale green to gray colum. They often attach sand, small pebbles and bits of shell to their body exterior using adhesive papillae cells (verrucae) located on the column The mouth is ringed with pink or purple tentacles which surround a broad oral disk. Behavior: Aggregating anemones have the ability to reproduce asexually by dividing into two identical individuals. Colonies, therefore, are genetic clones. Upon close inspection, one may notice that colonies are typically separated by a narrow anemone-free path. This is because when genetically distinct individuals come into contact with one another they recognize that they are from different colonies and a violent battle ensues. Using nematocyst-laden tentacles that are club-shaped, neighboring colonies repeatedly beat and sting each other. BLACK OYSTERCATCHER Haematopus bachmani Size: 8" in height. Habitat: A non-migratory, rocky-shore bird. Appearance: A large shorebird with black plumage, pink legs, and red-rimmed yellow eyes. Its long, thin, bright orange bill is used to catch prey from crevices, mussel beds and rocks. It has a characteristic high-pitched piercing call, which can often be heard above the noise of the surf. Ecology: Oystercatchers forage at low tides on a variety of intertidal animals, but especially on mussels and limpets. As a mussel gapes open when splashed by a rising tide, they are vulnerable to oystercatcher predation. The bird must deliver a quick, sharp stab between the two shells and sever the adductor muscles so that the mussel doesn’t close down on the oystercatcher’s beak. Once inside, the oystercatcher will withdraw the meat and swallow, yum! With limpets, a true treat, oystercatchers will jab at the edge of the shell in order to dislodge the limpet from a rock. The oystercatcher will then shake out the meat and swallow it in one gulp. Look for empty limpet shells that have a nick out of their edge. This is a sign they have been eaten by an oyster catcher. BROODING ANEMONE (proliferating anemone) Epiactis prolifera Size: Up to 4” tall and 2” in diameter at the disk. Habitat: Intertidal and shallow subtidal. Appearance: Come in a variety of colors including pink, green, brown and orange, with characteristic white markings at the bases of the tentacles. The oral disk and column have radiating white stripes. Ecology: Eggs of mature females are fertilized by planktonic sperm in her digestive cavity. Once the embryos develop into free-swimming larvae they escape through the oral disk and settle on the parents column where they live for about 3 months. As they develop into juvenile anemones they crawl away from the parent. If you look closely, you can see the developing juveniles with your naked eye. This is even more spectacular looking through a hand lens! BULL KELP (Bullwhip) Nereocystis luetkeana Size: Up to 100 feet long, this kelp is one of the largest in the world, and it can grow more than 5” in a day. Lifespan: Most of these plants rarely live longer than a year, and usually do not survive the harsh winter storms of the Pacific Northwest. Habitat: This kelp grows in the subtidal zone, but is commonly found washed ashore on sandy beaches or in the rocky intertidal. Appearance: A long, hollow stem with a bulbous float with four flat blades is connected to the ocean floor by its amazingly strong holdfast. Human use : This kelp has provided many uses for people of the past and present. Historically, people cut off the bulbous end to be dried and then used as a vessel to carry water. This species is edible; pickling is one way people have chosen to eat it. Dried pieces have often become part of wind chimes or other ornamental objects. It can also be a great jump rope. BY-THE-WIND SAILOR (sail jellyfish) Velella velella Size: up to 3” wide. Lifespan: About 1 month. Habitat: Found worldwide in tropical and temperate waters. This pelagic animal spends most of its time floating among the surface of offshore waters. In the rite of spring, however, west winds cast ashore millions of these oceanic hydrozoans forming a blue fringe along the beach. Appearance: By the wind sailors are a colony of specialized polyps, some of which are for feeding, others for defense and yet others for reproducrion. They are dark blue in color with a triangular, flexible, and upright sail. They use air-filled floats to cross surface waters. Ecology: A jelly to the core, V. velella has an interesting lifecycle, which includes both a polyp, which is attached to the sea floor and medusa, the floating planktonic organism. The life stage we see washed up on our beaches has a central feeding polyp surrounded by reproductive polyps that dangle into the sea. The reproductive polyps give rise to meduses that sink to the ocean floor, grow and then sexually reproduce larvae. These larvae eventually grow up to become the pelagic-polyp form we see. The polyp form can also reproduce asexually. V. velella feeds on fish eggs and crustacean larvae as well as symbiotic single-celled algae. The vibrant blue color of V. vellela arises from carotenoid pigments ingested in their prey. These pigments are then modified to become blue in the V. vellela’s skin. This bright blue coloring serves to protect the organism from excess light when floating on the sea surface. CALIFORNIA SEA LION Zalophus californianus Size: Females weigh 200 to 400 pounds and are up to six feet in length. Males weigh 500 to 750 pounds and grow up to 8 feet long. Diet: Fish, Shellfish, Squid. Habitat: California Sea Lions breed in southern California and Mexico. The individuals that we see here along the Oregon coast are males traveling to or from waters as far north as Alaska. These sea lions are commonly seen just offshore, but can be seen swimming in some marinas and lounging on the docks. Appearance: These sea lions are easily identifiable by their incredibly loud bark. When dry they are light brown, and when wet they are much darker. Males have a bony crest on their head that grows larger with age. All Sea lions can be distinguished from seals by the way they move. Observe how sea lions can pull their flippers under their body for walking. Seals, on the other hand, can't use their flippers in this fassion and must scoot along on thier bellies instead. Human Interaction: California Sea Lions have become habituated to humans and have taken advantage of our interactions with the environment. They have learned that fishing boats provide an abundant source of food, and do Dams, such as Bonneville, which create obstacles for salmon during their annual migration. Many salmon fishermen have a strong aversion towards these lea lions. CORALINE ALGAE (Coral seaweed) Corallina sp. Size: There are both encrusting and branching forms of coralline algae. The encrusting type can cover large areas, but is only about 1/16" thick. The branching type can grow up to 6” long. Habitat: These perennial algae thrive in rocky areas, in the low intertidal and subtidal zones, as well as in tidepools. Appearance: These are red algae which are hard and bumpy becasue they contain chalk. They often grow on the calcareous tubes of worms, and the shells of various mollusks. The branching form looks somewhat like coral when submerged in water. It has distinct segments and is stiffer than most algae, but still flexible. Ecology: This type of algae is a prominent feature in the intertidal ecosystem due to the calcium carbonate chalk it incorporates into its body structure, making it unpalatable to most organisms. Only a few species of mollusk, such as the whitecap limpet or the lined chiton feed on coralline algae. Since the algae cannot evade grazers, it often uses them as a substrate upon which to grow. The shell of one of its major predators is often the safest place for the algae to grow, as it is then out of reach. Studies have shown, in fact, that the tiny white reproductive structures of encrusting coralline algae are more often found on the shells of grazers than on rock substrates. GIANT GREEN ANEMONE (solitary anemone) Anthopleura xanthogrammica Size: Up to 12” in diameter and 12” tall. Habitat: Found in tidepools and rocky shores, as well as at depths of 50’ or more. Appearance: Dark olive-brown column with bright emerald green oral disk and tentacles. Ecology: These large, seemingly solitary animals actually have a very close knit, mutualistic relationship with green algae which gives them their color. The algae live inside the anemone consuming carbon dioxide and nitrogenous wast given off by the animal. In return, the algae give organic compounds to the anemone for its growth. GIANT PACIFIC CHITON (Gumboot) Cryptochiton stelleri Size: Growing up to 13" in length, this organism is the largest chiton found in the world. Lifespan: Up to 25 years. Habitat: Found in protected rocky areas of the lower intertidal. Appearance: This organism looks like a wandering meatloaf, but don’t be mistaken! The eight calcareous plates, characteristic of all chitons, lay hidden beneath a thick, leathery covering. The red-brown girdle contrasts with the yellow-orange foot and gills of the underside. Ecology: While other chiton species are nearly impossible to remove from rocks, the Gumboot can be easily picked up to observe the underside. The majority of the bright yellow underside is the chiton’s foot used for locomotion. Lighter colored fibrous parts around the edges of the underside are the chiton’s gills. Look carefully and you may see a worm that lives in the chiton gills. If you choose to pick up one of these creatures be sure to put it back exactly where it was found. GOOSENECK BARNACLES Pollicipes polymerus Size: 1"-2" tall. Habitat: Living on rocks in the intertidal zone. Diet: Filters small crustaceans and other planktonic species from the water. Appearance: This animal is connected to the rock by a dark, rubbery, stalk. Atop the stalk are white shell plates. Ecology: This barnacle is commonly found living with the black mussels (Mytilus californianus) is the rocky intertidal. They are found in tightly packed clusters. The stalk of the animal contains reproductive organs and the cement gland that keeps the animal attached to the surface of rocks. The rest of the animal is in the upper part behind the shell plates. To feed the shell plates open up and long, feathery appendages extend out into the water to catch food. HARBOR SEAL Phoca vitulina Size: These mammals weigh roughly 250-400 lbs. and reach a length of about 5’. Lifespan: Up to 30 years. Diet: Feed on a variety of fish. Habitat: Because they are less equipped for on land mobility than are sea lions, harbor seals are often seen perched on lower or slightly submerged rocks. They are also often spotted on sandy beaches, especially when pupping. Appearance: Their spotted coats vary in color from silver-gray to black to dark brown. They have small flippers and lack external ear flaps. Ecology: Harbor seals remain in our local near shore waters year-round. In the spring mature females bear pups weighing roughly 30 lbs. Mothers nurse their young for 3-4 weeks, during which time one can often spot the pair lounging on sun-bathed rock outcroppings or swimming in the waves among the bull kelp. Pups are skilled swimmers at birth, though they are often seen resting on mom’s back. HERMIT CRABS Size: Most inhabit shells that are one inch tall or smaller. Habitat: All parts of the rocky intertidal, usually underwater or under rocks at low tide. Diet: Hermit crabs feed primarily on algae, but will eat other plant and animal material. Appearance: The crabs have no hard covering to their bodies so they protect themselves by living in the shells of other mollusks. If the crab is inactive all this will be seen is the shell. When active the crabs head, antennae, pincers, and walking legs will extend out of the shell. As the crab grows it needs to find a larger shell. This is why it is important to leace empty chells in teh intertidal and not collect them to take home. Ecology: Hermit crabs can provide great amusement. Some species are so skittish that simply passing by their tidepool causes them to pull back into their shell. This sudden retraction and loss of footing often sends the crab and shell tumbling down to the bottom of the pool. Try picking up a shell and patiently waiting as the crab will slowly emerge and begin walking accross the palm of your hand. NORTHERN ELEPHANT SEAL Mirounga angustirostris Size: Males weigh up to two and a half tons and can be over fifteen feet long. Females weigh around 1200 pounds and grow to ten feet in length. Diet: Skates, rays, squid, octopus, eels, small sharks. Habitat: These seals spend most of the lives out in the deep waters of the open ocean. They can hold their breathes for up to 80 minutes, and the average depth of their dives is between 900 and 15oo feet. Dives have been recorded of 4,000 feet. Appearance: This species is the largest seal. They are brown to grey in color. Males have a large protruding snout that is used when they make a loud noise on the breeding ground. Ecology: Despite their adaptation to living in the open ocean and diving to great depths, these seals still have to come ashore twice a year, once to breed and once to molt. When they are molting these seals rest on beaches loosing their hair and some layers of skin for about three weeks. Due to their restful behavior while on land, these seals are often mistaken for giant logs. NUDIBRANCHS (sea slugs)

Size: This highly diverse class of organism ranges from a fraction of an inch to a foot in length. Habitat: Often found on rocks, kelp, mud, and sponges of the intertidal and subtidal zones. Some species are pelagic. Diet: Nudibranchs are carnivores that feed on sessile animals such as hydroids, sea anemones, soft corals, bryozoans, sponges, ascidians, barnacles and fish eggs. Appearance: Nudibranchs have various shapes, colors and patterns. The most locally common types are the dorid nudibranchs and the aeolid nudibranchs. Dorids have a flattened body shape, paired sensory projections on the head, and often a retractable gill plume at their back end. Aeolids are distinguishable from the dorids by the often colorful and flashy cereta (gills that are tentacle-like in appearance) protruding from their backs. Ecology: Some aeolid nudibranchs ingest the specialized stinging cells of cnidarians, passing them through their digestive tract both intact and unfired. The nudibranch then transfers these stolen stinging cells from branches of its digestive tract into its cerata (gills) and uses them for its own defense. Some pelagic species are even known to ingest and retain the stinging power of the Portuguese Man of War! If while observing a nudibranch, you also notice close by a fleshy material attached to a substrate in an intricate pattern you are possibly the lucky observer of a nudibranch egg mass. A nudibranch has a gonopore on one side of its body from which it secretes a mucus-like membrane filled with thousands of egg capsules. It lays the egg mass by traveling in a circle with the gonopore facing inward. This way the animal avoids walking over its own egg mass, and the eggs are kept in a tight spiral. PURPLE SEA URCHIN Strongylocentrotus purpuratus Size: 1” – 4” in diameter . Lifespan: Up to 50 years. Habitat: Lives intertidally up to 525’ deep from southern Alaska to Mexico. Found frequently in kelp forests and on algae covered rocks. They erode the rocks they live on forming depressions over time. Appearance: Covered in purple calcareous spines that protrude out of a dome-shaped shell (test). When observed in water you may notice long extended tube feet as well as tulip-shaped pinchers (pedicellariae) that lie between the spines. Purple urchins are often found decorated with pieces of shell, rock, or algae from their environment, which stick to their tube feet. This decoration helps to protect them from UV light, desiccation, and predators. Frequently asked questions: 2.What do purple urchins eat? 3.What predators does a purple urchin have? 4. Why do purple urchins live in pits? 5. Do they make their own pits? 6. Do people harvest purple urchins? STELLAR SEA LION Eumetopias jubatus Size: Females weigh around 600 pounds, and grow to seven feet in length. Males can weigh over one ton and grow up to ten feet in length. Diet: Fish, Squid, Octopus. Habitat: These sea lions are residents of the Oregon coast. Appearance: These are the largest sea lions. When dry the are much lighter in color than the California Sea Lion. Ecology: Many sea lions of both sexes can be seen resting on the rocks from Simpson’s Reef Overlook in Cape Arago State Park. While not as significant a threat to the salmon and other freshwater fish populations as the California Sea Lion, they are found in the Columbia River as well. SUNFLOWER STAR Pycnopodia helianthoides Size: Around 2’ in diameter. Lifespan: 3-5 years. Habitat: Found in the rocky intertidal. Appearance: These large radially symmetrical sea stars come in a variety of colors including, purple, purple-gray, red-orange, and orange. Adult sunflower stars have 15- 24 arms, which, like all seastars, they can regenerate when lost. Some explorers of the tidepools mistake these sea stars for an octopus because of their large, soft, and flexible body. On close inspection you may notice that their bodies are covered in small calcareous spines. The underside has thousands of transparent-yellow tube feet, which are used for suctioning, walking across surfaces and feeding. Ecology: A top predator in the tidepools, Pycnopodia helianthoides has the ability to eat a wide variety of organisms including, crabs, chitons, sea urchins, abalone, turban snails, and other sea stars. Its large size, as well as its ability to move 1 meter/minute, allow it to quickly and easily overtake its prey. The escape responses of many intertidal invertebrates to a close by sunflower star are quite exciting to observe. For example, a sea urchin will walk away, flatten its spines and stick out its bright white pinchers in the presence of a sunflower star. Another example is with the cockle. In this relationship a chemical cue from the sunflower star causes the cockle to dramatically protrude its foot. The foot is almost twice the size of its shell and is very quickly shot out. The cockle will use foot to push itself away.

|