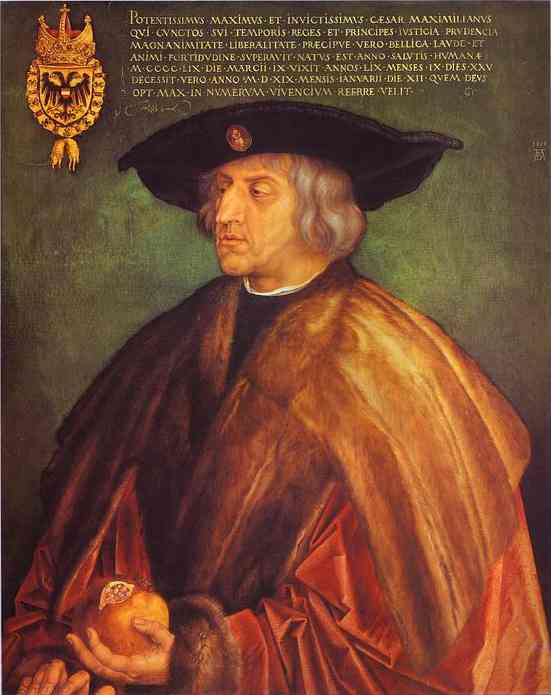

Image: Albrecht Dürer, Portrait

of Maximilian I (1519). Oil on panel. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Austria.

Image Source: Olga's

Gallery.

Image: Albrecht Dürer, Portrait

of Maximilian I (1519). Oil on panel. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Austria.

Image Source: Olga's

Gallery.

...people will look for the Empire in Germany and not find it there; and as a result strangers will occupy our lands and will divide us up among themselves, and in this way we shall become subject to another nation.Early attempts at reforms were made under Emperor Sigismund (1410-1437), who had presided over the Council of Constance. That assembly had offered a model for how the Empire might go about the project of reform. Sigismund tried create a reform alliance with the German cities, but his efforts failed in the face of resistance to reform from the Imperial Electors. From the 1450s on, the initiative came from princes eager to place more restrictions on the power of the Emperor as part of a reform package. When an imperial reform movement emerged in the late 1480s, two coalitions formed:

1) The Emperor’s Party:

The first group, consisting of the Habsburg Emperor and his allies among the

imperial cities and the weaker princes of the realm, supported reforms that

would (a) enable the Emperor to exploit Germany's considerable resources more

effectively than in the past, through such innovations as a regular system of

imperial taxation; and that would (b) enable the Emperor to administer Germany

in absentia, such as an imperial governing council, if it could be kept

under the Emperor's control. In short, Maximilian I and his party wanted an

Empire that would maintain the peace during his absences, to the benefit of

his dynasty, and at minimal cost to Austria.

2) The Princes’ Party:

Led by Nicolas of Cusa’s pupil, Archbishop-Elector Berthold von Henneberg of

Mainz, the imperial Archchancellor,

the princes’ party saw reform as a means to give the Empire a more clearly federal

structure. The main instrument of such a reform would be an imperial

court system that would put an end to private wars and subject conflict

among princes to the arbitration of courts of law. In addition, the Princes'

party envisioned a standing administrative council for the Empire that was capable

of acting with considerable executive autonomy from the Emperor.

This characterization of the interests involved only begins to describe the

complexity of reform politics during the last decade of the fifteenth century

and at the beginning of the sixteenth. An example: as archduke of Austria, Emperor

Maximilian was also a prince of the realm, and in this capacity he shared many

interests with other princes of similar power and stature. Reforms that served

him as a prince might benefit the other princes as well. But as Emperor, Maximilian

could also make common cause with the small-fry lords of the Empire, the imperial

knights, as a counterweight against the more powerful princes.

A deadlock formed between the two sides, which was broken

when the Emperor’s financial needs proved so great that he could no longer afford

to continue without an infusion of new money from the Reichstag; the

first step toward reform was taken in 1486, when after long negotiations the

Reichstag proclaimed a 10-year ban on private wars between lords. This

was the first in a series of general, imperial truces and would provide the

legal basis for reforms of the Empire's judicial system.

The Reichstag at Worms, 1495

But the most important and lasting moves toward reform were taken at an assembly

of the imperial estates held at the Rhineland city of Worms in 1495. At the

forefront of its efforts stood the problem of private warfare between princes,

nobles, and free cities. To address the problem, the assembly adopted a series

of far-reaching changes. To begin with, the Reichstag proclaimed the

“Perpetual Peace,”

which built on the earlier truce and decreed that in future, no member

of the Empire should feud with or cause harm to any other. Violations of this

“Perpetual Peace”

would be treated in courts of law, not on the field of battle. By this means,

the Reichstag sought to put an end to feuding among the princes and free

cities of Germany.

Conclusion

When Archbishop Berthold von Henneberg died in 1512, much of the initiative

reform expired as well. On balance, the results of the reform movement were

mixed: few had been satisfied with the existing state of German affairs; many,

if not most elites wanted change in the direction of greater peace and security.

But few could agree on proper course of reform, and fewer still were in any

position to impose their version of reform on the rest. In the end, the Empire

got a little of everything: new federal institutions, some of them quite effective,

but no strong federal power; a stronger monarch in the person of Maximilian

I and his successor, Charles V, but not a strong monarchy.

Another lasting effect of the reform movement was to entrench emerging regional differences in the Empire's political culture and structure. Already in the fifteenth century, the northern and eastern regions of the Empire were dominated by relatively large duchies and counties, in which the judicial monopoly of dukes and counts was relatively well established. During the period of reform, these powerful, northern princes still risked relatively little by failing to participate in a Reichstag or adhering to its resolutions. But small-fry princes and free cities located in the politically fragmented regions of central, western, and southern Germany enjoyed no such impunity. They could refuse to pay the Common Penny or honor Reichstag resolutions only at grave risk. The result was to encourage the northeast-southwest bifurcation of Germany: large territorial states in the north and east, an extremely fragmented political landscape with far livelier federal institutions of justice and decision making in the southwest.

But we must resist the temptation to seek the origins of all the Empire's strengths

and weaknesses in the outcomes of the imperial reform movement. Most modern

diagnoses of success and failure take as their yardstick the degree to which

a particular change moved Germany in the direction of national state-building

and ethno-political unification (according to one version); others have diagnosed

success and failure according to the standards of social or economic "progress"

toward a particular world-historical goal. But as Thomas Brady and others have

pointed out, the Empire's reformers had no such goals in mind. If Maximilian

I had had his way, an entirely different political landscape would have emerged

from the reform era, with an enlarged and powerful Austria--stretching from

what is now Belgium and the Netherlands and what is now western

France across what is now southern Germany into what is now Austria--at

the core of a federation of cities and communes throughout the Empire. This

project failed, not so much because it did not lead to nation building or social

transformation, but because Reformation and the religious divisions it produced

shattered its foundations and chances for realization[1].