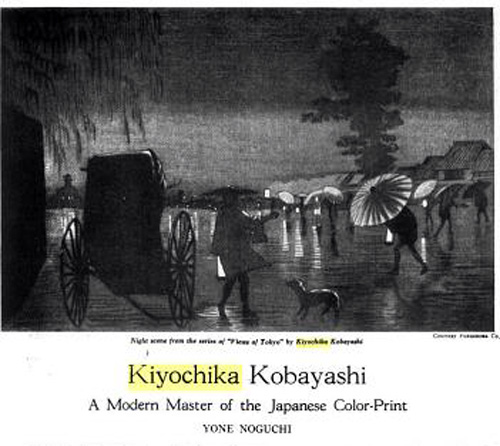

KIYOCHIKA KOBAYASHI, who passed away quite recently, is interesting at least in the series of the "Views of Tokyo" (some one hundred in number), published between 1874 and 1879, because he was in truth like an impressive burst of dawn from a still night, the very first artistic voice of the new regime, awakening sudden and fresh from the old dreams; his attempt was to create his own special domain outside of the ever-sensitive languor of the women of Utamaro, or the prismatic irony of actors of Sharaku, or the fanciful jugglery of life of Hokusai, or the nocturnal melody of scenery of Hiroshige. When I say that his artistic lungs, although they were not so vigorous or big, were full of the new air of morning, I mean that he was interpreting the new, therefore highly bizarre, phases of suddenly awakened Tokyo, whose determined curiosity made her the first of all to shake off even the beauties of life in the Tokugawa feudalism; the telegraph poles in the "Snowy View of Ryogoku," or the Western dress in the "Tea shed on the Atago Hill," or the glass windowed foreign building in the "Kiyobashi Bazaar," new Japan's first adoption from the West, must have been viewed by Kiyochika with the huge eyes of a barbarian whose admiration perhaps goes first to the wicked side of a new thing. Kiyochika's accidental realism of art, as I said before, corresponding to many a phase of new Tokyo characterized by an accidental leap rather than by a systematic advance, is indeed a song liberated from the fear and pain of old remembrance, as if a first note of a new bird awakened into the joy of sunlight; his imperfection in technique (he ever kept a certain amateurish wildness) sharpening or breaking the general music was, I might say, balanced by the flowing spirit of youthfulness whose peculiar pungency Tokyo of forty years ago alone understood. If you can imagine the sensation of a people facing the strange West after a thousand years' sleep, you would not, I am sure, laugh away his pictorial adventure introducing into a color-print the gesticulation of light on the water or the changing manner of clouds and shadows.

The color-print of the past was an artistic "extra territoriality" where the "carpe diem" romanticism enacted a temporary masquerade, was a temple, not altogether holy, even vulgar, where the artists or artizans were innocent enough not to suspect their own artistic belief; when the color print was near its death with Hiroshige or Kuniyoshi, it was from being exhausted in strength and love; it was quite a natural death. But behold, out of the ruins leapt New Japan, at least New Tokyo. When the color-print seemed to revive, although merely temporarily, in the hand of Kiyochika Kobayashi, it was as if the room was suddenly brightened by a peeping light through a hole or chink; it was only natural that Kiyochika forgot all his artistic prudence, risking himself in the freedom that he was newly acquainted with. He was bizarre, because he had no time for reflection or rearrangement of himself; whatever the shortcomings of his art may be, his note of exultation after the feudal passivity, exultation in the liberated plebeianism, was distinguished and genuine. I defy the critic who inclines to call him prosaic.

One who has tasted enough of the poetical stillness of heavy snow or cross-barred rains will be surely glad to turn to Kiyochika, who lived from laugh to laugh, from song to song; he was a pictorial singer tantalized by the gleam of realism or reality. His joy of life and the world was not, I think, so sure and compact; how could it be when he lived in the age whose artistic charm was always pointed and sharpened by its own restlessness? He was the return of the warm blood that quickened and strengthened the art of the color-print, when the circulation, since the time of the First Hiroshige, had been arrested by stupid repetition; we Japanese should be thankful to Kiyochika for his red blood, which, although he was faulty, made him a living artist, not an artistic machine. Therefore, when he committed a fault, he had every chance for making a true confession; I believe that he should have been glad to live in his own days, challenging and ephemeral, those days of some forty years ago, and to breathe their mocking spirit. I may apply to him a phrase of an English poet that he "cherished every hour that strayed adown the cataract of days."

It seems that his artistic mind was nursed wisely or foolishly, sometimes by Chingaku, sometimes by Zeshin, and sometimes by Kyosai; but his artistically irresponsible roguishness soon made him adopt a vagabond life, now in the snowy North, then on the singing billows with uncouth naked fishermen, when the death of his father obliged him to experience, as the legal heir, official tyranny from the disagreeable contact with his superiors. He was of a Samurai family of some lower class, like the First Hiroshige. When he was wandering in the Northern wilderness, his reckless spirit made him join at once with the feudal army who were fighting against the Imperial flag, only to hasten the Restoration; he followed the last Shogun to Shizuoka. Being called again by a wanderer's freedom, it is said that he formed a troupe of fencers for public performance, with whom he led a lawless life till he arrived at Nagoya by the Tokaido road famous in Hiroshige's color-prints. He was alone in his wandering in Ise Province as his troupe had already disbanded; and it is said that it was somewhere in this province that he saw for the first time a Western picture of a landscape, perhaps a steel engraving or color reproduction, whose extraordinarily strong impression upon his mind inspired him later on to issue the series of the "Views of Tokyo."

When he returned to Tokyo in 1871 or 1872, he found the new Capital with a strange and curious aspect from its sudden surrender to the West; it seems that his artistic curiosity, ever so hungry for a new sensation, must have been well satisfied by those striking changes that the Western winds brought. His sensitive temperament that had been growing more sensitive from his long wandering made him grasp the flexible minuteness of the Western art which he studied under a certain Wagman for two years; but when he returned again to his original Japanese art, the Western technique which he had learned from his foreign teacher helped it to gesticulate more freely and impressively.

He called his newly invented art the "Sunlight Picture"; he duly persuaded in 1874 Ohira, then a well-known color-print publisher at Ryogoku, and later on Gusokuya, another publisher in Ningyocho, to issue the said series of the "Views of Tokyo." The prints that were published by Ohira between 1874 and 1876, small in number, now quite rare, show a far more marked Western influence than his later productions, in their coy prudence with the matter of light and shadow, in a suspicious particularity of observation and in youthful ambition; most of them are pictures of daylight. He gradually lost his Western affection in the work he published after 1876 or 1877; it seems that his poetical audacity in using the material limitations of the color-print made him successful, as in the case of the First Hiroshige, in many nocturnal sketches where his art and technique gladly blended in one music. As I said before, the manner of the light's reflection on the ground or river, the various forms of clouds, sometimes with spilled gleam, are an artistic experience that the First Hiroshige never dreamed of; what I want to emphasize about Kiyochika's work is his pictorial expression of the new feeling of the city people of forty years ago, wildly eager for wonder and excitement, therefore restless and sometimes treacherous.

Note: Yone Noguchi, or Yonejirō Noguchi, born 野口 米次郎 / Noguchi Yonejirō (December 8, 1875 - July 13, 1947), was an influential Japanese writer of poetry, fiction, essays, and literary criticism in both English and Japanese. He was the father of the sculptor Isamu Noguchi. (Wikipedia http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yone_Noguchi)

The color-print of the past was an artistic "extra territoriality" where the "carpe diem" romanticism enacted a temporary masquerade, was a temple, not altogether holy, even vulgar, where the artists or artizans were innocent enough not to suspect their own artistic belief; when the color print was near its death with Hiroshige or Kuniyoshi, it was from being exhausted in strength and love; it was quite a natural death. But behold, out of the ruins leapt New Japan, at least New Tokyo. When the color-print seemed to revive, although merely temporarily, in the hand of Kiyochika Kobayashi, it was as if the room was suddenly brightened by a peeping light through a hole or chink; it was only natural that Kiyochika forgot all his artistic prudence, risking himself in the freedom that he was newly acquainted with. He was bizarre, because he had no time for reflection or rearrangement of himself; whatever the shortcomings of his art may be, his note of exultation after the feudal passivity, exultation in the liberated plebeianism, was distinguished and genuine. I defy the critic who inclines to call him prosaic.

One who has tasted enough of the poetical stillness of heavy snow or cross-barred rains will be surely glad to turn to Kiyochika, who lived from laugh to laugh, from song to song; he was a pictorial singer tantalized by the gleam of realism or reality. His joy of life and the world was not, I think, so sure and compact; how could it be when he lived in the age whose artistic charm was always pointed and sharpened by its own restlessness? He was the return of the warm blood that quickened and strengthened the art of the color-print, when the circulation, since the time of the First Hiroshige, had been arrested by stupid repetition; we Japanese should be thankful to Kiyochika for his red blood, which, although he was faulty, made him a living artist, not an artistic machine. Therefore, when he committed a fault, he had every chance for making a true confession; I believe that he should have been glad to live in his own days, challenging and ephemeral, those days of some forty years ago, and to breathe their mocking spirit. I may apply to him a phrase of an English poet that he "cherished every hour that strayed adown the cataract of days."

It seems that his artistic mind was nursed wisely or foolishly, sometimes by Chingaku, sometimes by Zeshin, and sometimes by Kyosai; but his artistically irresponsible roguishness soon made him adopt a vagabond life, now in the snowy North, then on the singing billows with uncouth naked fishermen, when the death of his father obliged him to experience, as the legal heir, official tyranny from the disagreeable contact with his superiors. He was of a Samurai family of some lower class, like the First Hiroshige. When he was wandering in the Northern wilderness, his reckless spirit made him join at once with the feudal army who were fighting against the Imperial flag, only to hasten the Restoration; he followed the last Shogun to Shizuoka. Being called again by a wanderer's freedom, it is said that he formed a troupe of fencers for public performance, with whom he led a lawless life till he arrived at Nagoya by the Tokaido road famous in Hiroshige's color-prints. He was alone in his wandering in Ise Province as his troupe had already disbanded; and it is said that it was somewhere in this province that he saw for the first time a Western picture of a landscape, perhaps a steel engraving or color reproduction, whose extraordinarily strong impression upon his mind inspired him later on to issue the series of the "Views of Tokyo."

When he returned to Tokyo in 1871 or 1872, he found the new Capital with a strange and curious aspect from its sudden surrender to the West; it seems that his artistic curiosity, ever so hungry for a new sensation, must have been well satisfied by those striking changes that the Western winds brought. His sensitive temperament that had been growing more sensitive from his long wandering made him grasp the flexible minuteness of the Western art which he studied under a certain Wagman for two years; but when he returned again to his original Japanese art, the Western technique which he had learned from his foreign teacher helped it to gesticulate more freely and impressively.

He called his newly invented art the "Sunlight Picture"; he duly persuaded in 1874 Ohira, then a well-known color-print publisher at Ryogoku, and later on Gusokuya, another publisher in Ningyocho, to issue the said series of the "Views of Tokyo." The prints that were published by Ohira between 1874 and 1876, small in number, now quite rare, show a far more marked Western influence than his later productions, in their coy prudence with the matter of light and shadow, in a suspicious particularity of observation and in youthful ambition; most of them are pictures of daylight. He gradually lost his Western affection in the work he published after 1876 or 1877; it seems that his poetical audacity in using the material limitations of the color-print made him successful, as in the case of the First Hiroshige, in many nocturnal sketches where his art and technique gladly blended in one music. As I said before, the manner of the light's reflection on the ground or river, the various forms of clouds, sometimes with spilled gleam, are an artistic experience that the First Hiroshige never dreamed of; what I want to emphasize about Kiyochika's work is his pictorial expression of the new feeling of the city people of forty years ago, wildly eager for wonder and excitement, therefore restless and sometimes treacherous.

Note: Yone Noguchi, or Yonejirō Noguchi, born 野口 米次郎 / Noguchi Yonejirō (December 8, 1875 - July 13, 1947), was an influential Japanese writer of poetry, fiction, essays, and literary criticism in both English and Japanese. He was the father of the sculptor Isamu Noguchi. (Wikipedia http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yone_Noguchi)