Prints in Collection

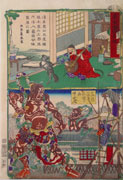

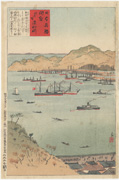

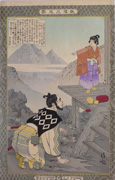

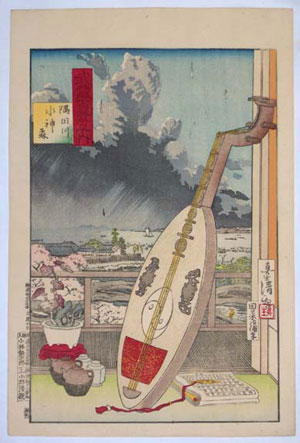

Meguro Arsenal from the series

One Hundred Views of Musashi,

1884

IHL Cat. #610

Irokezuku sakekuse from the series Sake kigen jūnisō no uchi, 1885

IHL Cat. #993

-intentionally left blank-

-intentionally left blank-

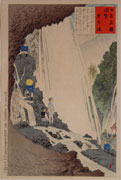

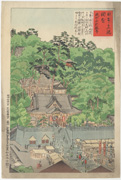

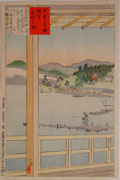

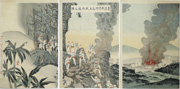

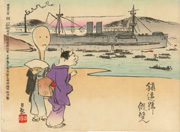

Prints from the series

Famous Sights of Japan

Monkey Bridge

1896

IHL Cat. #1840Yumoto Hot Spring

1896

IHL Cat. #129

Narita-san Shinshōji Temple, 1897

IHL Cat. #1842

Cape Kannon

1897

IHL Cat. #877Inner Valley at Tsukigase

1897

IHL Cat. #340 and #1843Tsukuba Mountain Seen from Sakura River at Hitachi

1897

IHL Cat. #517

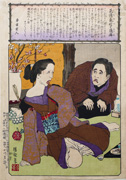

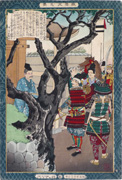

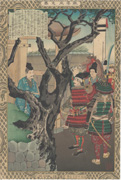

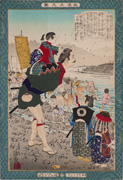

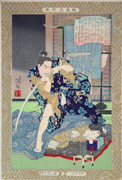

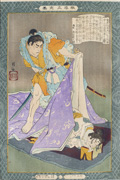

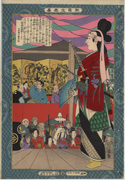

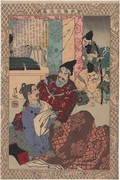

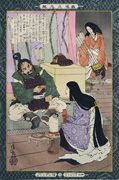

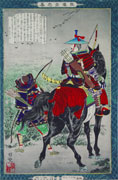

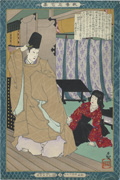

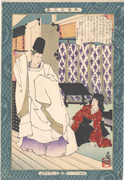

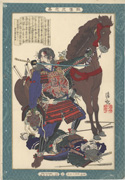

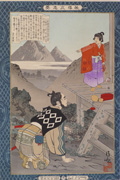

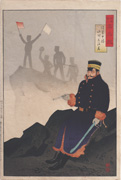

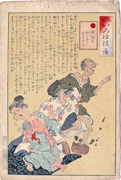

Prints from the series

Instructive Models of Lofty Ambition

Fukuchi Gen’ichirō

October 26, 1885

IHL Cat. #881

IHL Cat. #611

Ono-no Tofu

May 21, 1886

IHL Cat. #40

IHL Cat. #496

Butsu Sorai

1886

IHL Cat. #1397

Koshikibu no Naishi

1886

IHL Cat. #759

1886

IHL Cat. #1401

Takemitsu Kikuchi

1886

IHL Cat. #1398

Uesugi Kagetora

1888

IHL Cat. #476

Uesugi Kagetora

1888

IHL Cat. #584

Sugawara no Michizane

April 1889

IHL Cat. #582

-intentionally left blank-Re-prints from the seriesInstructive Models of Lofty Ambition

Kesa Gozen

(re-issue), 1902

IHL Cat. #573

Ono-no Tofu

(re-issue), 1902

IHL Cat. #574

Sato Tsuginobu

(re-issue), 1902

IHL Cat. #575Dainin Kamitsukeno Katana

(re-issue), 1902

IHL Cat. #602

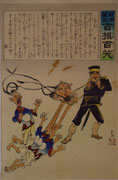

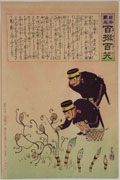

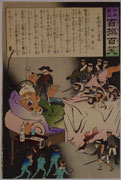

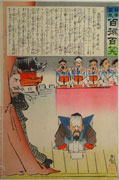

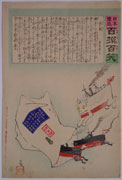

Prints from the series

Long Live Japan:One Hundred Victories, One Hundred Laughs

[Sino-Japanese War]

A Big Headache for Li Hongzhang A Big Headache for Li HongzhangSeptember 1894 IHL Cat. #108 | Going Bankrupt November 1894 IHL Cat. #538 | IHL Cat. #1218 |  Hubbub in the Dragon King's Palace Hubbub in the Dragon King's PalaceDecember 1894 IHL Cat. #274 | The Pig's Dismay December 1894 IHL Cat. #227 |

| Hell is Booming December 1894 IHL Cat. #380 | Pulling the Necks December 1894 IHL Cat. #379 | IHL Cat #1064 |  These are the Pescadores (Penghu)! These are the Pescadores (Penghu)! January 1895 IHL Cat. #228 |  A Thick-Skinned Face A Thick-Skinned FaceFebruary 1895 IHL Cat. #50 |

A Moaning Monologue in the Chinese Kyōgen A Moaning Monologue in the Chinese KyōgenMarch 1895 IHL Cat. #331 |  Mice in a Trap Mice in a TrapApril 1895 IHL Cat. #45 | April 1895 IHL Cat. #44 |

[Sino-Japanese War]

| January 1896 IHL Cat. #273 | -intentionally left blank- | -intentionally left blank- | -intentionally left blank- | -intentionally left blank- |

Prints from the series

Long Live Japan:One Hundred Victories, One Hundred Laughs

[Russo-Japanese War]

Extermination of the Suffering Russian Bear May 1904 IHL Cat. #1058 | -intentionally left blank- | -intentionally left blank- | -intentionally left blank- | -intentionally left blank- |

Tea House at Imadobashi

(after Kiyochika), c. 1930s

IHL Cat. #111

(after Kiyochika), c. 1930s

IHL Cat. #172

Biographical Data

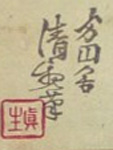

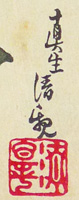

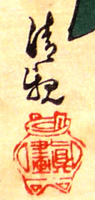

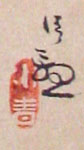

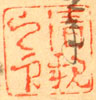

Family name: Kobayashi 小林; Childhood name: Katsunosuke 胜之助; gō: Hōensha 方円舎, Shinseirō 真生楼 and Shinsei 真生. Nikutei Karyō 肉亭夏良 is now assumed to be a gō (artist name) used by Kiyochika early in his career.*

*For a source on this see the website of 浮世絵文献資料館 http://www.ne.jp/asahi/kato/yoshio/kobetuesi/kiyotika-kobayasi.html

Sources: Kiyochika: Artist of Meiji Japan, Henry D. Smith II, Santa Barbara Museum of Art, 1998; Minato City Library, Japan website

http://www.lib.city.minato.tokyo.jp/yukari/e/man-detail.cgi?id=41&CGISESSID=dcd5fd43789c08a3a564dcfaa4f6ce9b

Biography

There is speculation that Kiyochika was introduced to Charles Wirgman (1832-1891), an English journalist and art instructor, and that he studied Japanese painting with Kawanabe Kyōsai (1831-1889)1, but the evidence is inconclusive, again leaving Kiyochika as likely being a self-taught artist. It is also reported that he studied photography with Shimo'oka Renjo (1823-1914), the father of Japanese photography.

Kiyochika was unique at his time for not having any allegiance to a master or school of art. Had he been born prior to the Meiji era and the new freedoms it brought, he would have been forced into a master-disciple relationship to pursue an artistic career.

It was Hara who helped pave the way for Kiyochika's employment as a political cartoonist for the Maramaru chinbun in 1882 where, for the next decade, Kiyochika drew weekly cartoons.

In 1883 Kiyochika married Tajima Yoshiko who had one daughter and was pregnant with a second. In 1886 he moved his family near the offices of the major newspapers. Kiyochika's last daughter Katsu, who was to become her father's biographer, was born in November 1894, during the height of the Sino-Japanese War (1894-1895).

Kiyochika's war prints also brought him other work such as the series One Hundred Views of Musashi* (1894-95) which showed the artist working in a more conventional style, as shown in the three prints below.

*Musashi being the name of the province that included Edo.

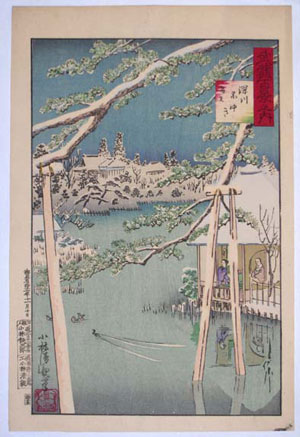

Despite the series promise of "One Hundred Views", only thirty-four images were released. "These prints partly imitated Hiroshige’s One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, but they have a very complicated relationship with their predecessor. The use of the vertical format is similar, as is the use of a close-up view against which is juxtaposed a faraway view. There is, however, a particularly conscious attempt on Kiyochika’s part to demonstrate how the city had been subject to Westernization."3 For an example, see the print Meguro Arsenal, IHL Cat. #610.

Famous Views of Tokyo

In 1896, twenty years after designing the first print in the series Famous Views of Tokyo, Kiyochika designed 28 prints as part of the series Views of the Famous Sights of Japan. See thumbnails at top of page for examples of prints from this series in the collection. For detailed information on this series see the article Views of the Famous Sights of Japan (Nihon Meisho Zue).

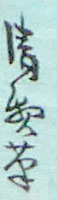

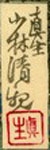

Kiyochika's earliest prints used the gō (art name) Hōensha 方円舎 and his given name Kiyochika 清親. "The use of one's given name in a signature was virtually unprecedented in the history of Japanese art, and at the time could have only have been used by those working in a purely Western style of painting..." On the Tokyo landscapes, he usually signed horizontally, often from left to right in the Western manner. He often appended hitsu (from the brush of) [or ga (drawn by)] to his name, as did many Japanese artists. In 1894 he took a new art name Shinsei 真生, written with the kanji for 'truth' and 'birth'. Kiyochika used Shinsei or simply Shin 真 for the rest of his life, although after the 1880s it appears on seals and not as part of his signature. In the late 1880s, Kiyochika began to drop the family name, Kobayashi, in his signatures and signed works simply Kiyochika. "In effect, his given name had in time become his art name, and on both paintings and prints from the 1890s until the end of his life, Kiyochika always signed simply 'Kiyochika,' reserving the family name Kobayashi for seals."

1 Smith does note that Kyosai was an "old friend" of Kiyochika's and that Kiyochika drew on Kyosai's spirit for much of his comic work.

2 Kiyochika: Artist of Meiji Japan, Henry D. Smith II, Santa Barbara Museum of Art, 1998, p. 8.

3 Beyond the Great Wave, James King, Peter Lang, 2010, p. 125.

last revision:

Sources: Kiyochika: Artist of Meiji Japan, Henry D. Smith II, Santa Barbara Museum of Art, 1998; Minato City Library, Japan website

http://www.lib.city.minato.tokyo.jp/yukari/e/man-detail.cgi?id=41&CGISESSID=dcd5fd43789c08a3a564dcfaa4f6ce9b

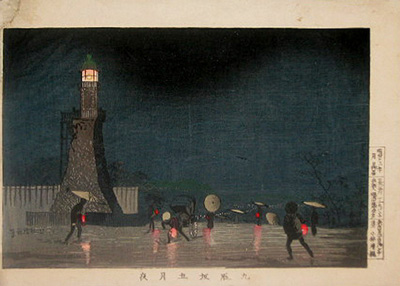

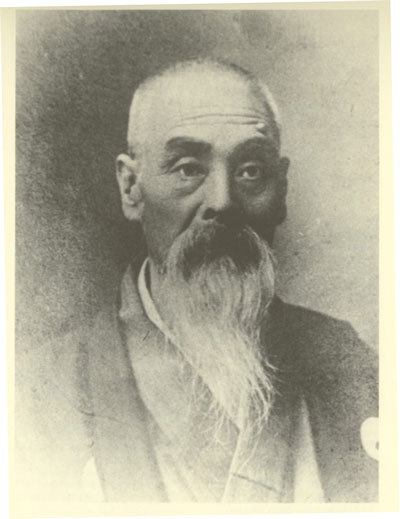

| ProfileKiyochika has been described as "the last important ukiyo-e master and the first noteworthy print artist of modern Japan."1 He is said to be the last ukiyo-e artist to lyrically depict Tokyo during the Meiji cultural enlightenment. Kiyochika, while best-known today as a print designer, was also an illustrator and cartoonist. Born in 1847 to a military retainer of the Tokugawa Shogun, he was a self-taught artist, although references are made to acquaintances with Japanese and Western artists. His landscape woodblock prints often depict scenes showing western influences and many are dramatically lit by the moon, newly introduced gaslights or fire. His greatest fame domestically came from producing senso-e (war prints) of the Sino-Japanese War. 1 Images from the Floating World, Richard Lane, Konecky &Konecky, 1978. Lane goes on to say that Kiyochika has also been described as "a minor hero whose best efforts to adapt ukiyo-e to the new world of Meiji Japan were not quite enough." |

Biography

First 30 Years

Little is known about Kiyochika's early life. Born in Edo as the son of the head of the Shogun’s granary, he was the ninth and last child of Kobayashi Mohei. His mother came from a long line of shogunal officials. At the age of 15 he inherited the family estate after his father’s death, but gave up the granary in 1868 to follow the last shogun, Tokugawa Keiki, to his new domain in Shuruga (now Shizuoka Prefecture.) He married in April 1870, a marriage that lasted six years, and it is reported that he worked as a fisherman while in Shuruga. He trained in the martial arts and sometime after 1870 he went touring with a group of performing swordsmen. He began his art career in 1874, after moving back to Tokyo with his wife and mother. His mother died shortly after returning to Tokyo and he divorced his wife in 1876.Art Training

The degree of Kiyochika's formal art training is uncertain and Smith says that he is likely self-taught. Kiyochika, it is said, described himself as working in the style of Iwasa Matabei (1578-1650) and Hishikawa Moronobu (c. 1618-1694) two of the founders of ukiyo-e.There is speculation that Kiyochika was introduced to Charles Wirgman (1832-1891), an English journalist and art instructor, and that he studied Japanese painting with Kawanabe Kyōsai (1831-1889)1, but the evidence is inconclusive, again leaving Kiyochika as likely being a self-taught artist. It is also reported that he studied photography with Shimo'oka Renjo (1823-1914), the father of Japanese photography.

Kiyochika was unique at his time for not having any allegiance to a master or school of art. Had he been born prior to the Meiji era and the new freedoms it brought, he would have been forced into a master-disciple relationship to pursue an artistic career.

Early Woodblock Prints: The Series Famous Views of Tokyo (Tokyo meisho) 1876-1881

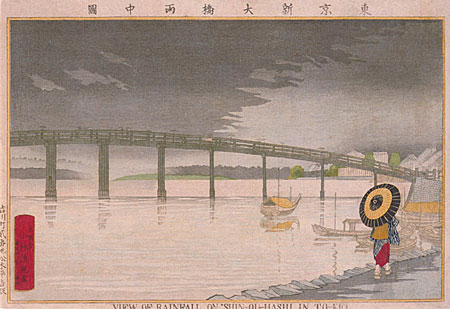

In 1876, working with the publisher Matsuki Heikichi [who also published many of Yoshitoshi Tsukioka's (1839-1892) prints], the print View of Rainfall on Shin-ou-hashi in To-kei was published. It was to be the first of 93 prints in the series Famous Views of Tokyo (Tokyo Meisho-zu.) This, and subsequent, prints in the series employed Western style perspective and realistically portrayed the effects of light and shadows in a style called kosenga (luminous images). Henry D. Smith II, a biographer of Kiyochika's, describes the series as follows: Source: Meiji Tokyo as Seen by Kiyochika, Henry D. Smith II, 1991 |  View of Rainfall on Sin-ou-hashi in To-kei (1876) View of Rainfall on Sin-ou-hashi in To-kei (1876) |

The Great Ryogoku Fire Incident

In 1878 Kiyochika and his second wife, a daughter of a Tokugawa retainer, moved near the west end of the Ryogoku Bridge to be closer to the Matsuki Heikichi publishing house. In November, his daughter Ginko was born. Sometime in 1881 or 1882 he separated from his second wife, a separation that was reportedly caused by Kiyochika's abandonment of his home and family during the great Ryogoku fire of January 1881. As the story goes Kiyochika abandoned his house to sketch the fire, returning in the morning to find his house gone, burned in the fire. Smith calls this scenario "fanciful." The fire did, however, result in the below, now-famous, print The Great Fire at Ryogoku Viewed from Hamacho.

The Great Fire atRyogoku Viewed from Hamacho

Kiyochika continued his association with the publisher Heikichi into 1881. In 1879 he also started working with a second publisher Fukuda Kumajirō, but in mid-1881 both publishers stopped issuing his prints. Smith suggests that the reason for the stoppage was that the prints were not selling as "his public had become jaded by his westernized style" and the later prints in the Famous Views of Tokyo series were "conventional and unimaginative."2 Working as a Satirist

To earn a living Kiyochika turned to a career drawing political cartoons, aided by Hara Taneaki (1853-1942), a former shogunal retainer turned Christian book seller, who published Kiyochika's comic series of woodblocks Thirty-Two Faces in 1882.

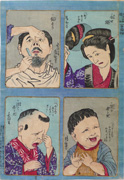

from the series "Thirty-Two Faces"

Top left - Wife lost her temper without her husband returning home.

Top right - Her legs have gone to sleep.

Bottom Left -The position of the finger.

Bottom right - Ouch, he knocked his head.

Top right - Her legs have gone to sleep.

Bottom Left -The position of the finger.

Bottom right - Ouch, he knocked his head.

It was Hara who helped pave the way for Kiyochika's employment as a political cartoonist for the Maramaru chinbun in 1882 where, for the next decade, Kiyochika drew weekly cartoons.

In 1883 Kiyochika married Tajima Yoshiko who had one daughter and was pregnant with a second. In 1886 he moved his family near the offices of the major newspapers. Kiyochika's last daughter Katsu, who was to become her father's biographer, was born in November 1894, during the height of the Sino-Japanese War (1894-1895).

Senso-e (War Prints) of the Sino-Japanese War

The patriotism engendered by the war drove a strong demand for battle illustrations and Kiyochika churned out hundreds of battle-scene triptychs and single-sheet battle scenes and war-related comic prints, such as the series Long Live Japan: One Hundred Victories and One Hundred Laughs. (Click on the series name for details.) These prints brought him his greatest domestic fame.

Naval Battle of the Yellow Sea (Yalu River)in Korea (Chôsen Hôtô kaisen no zu)

Two Series of Scenic Views

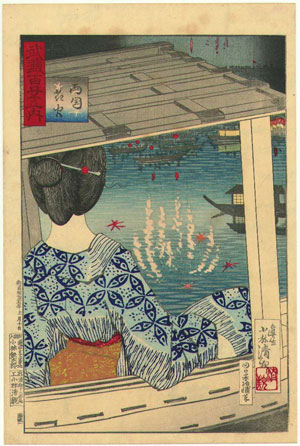

One Hundred views of MusashiKiyochika's war prints also brought him other work such as the series One Hundred Views of Musashi* (1894-95) which showed the artist working in a more conventional style, as shown in the three prints below.

*Musashi being the name of the province that included Edo.

Fireworks over Ryogoku from One Hundred Views of Musashi |  Fallen snow at Fukugawa from One Hundred Views of Musashi |  The Sumida River and Suijin Forest from One Hundred Views of Musashi |

Famous Views of Tokyo

In 1896, twenty years after designing the first print in the series Famous Views of Tokyo, Kiyochika designed 28 prints as part of the series Views of the Famous Sights of Japan. See thumbnails at top of page for examples of prints from this series in the collection. For detailed information on this series see the article Views of the Famous Sights of Japan (Nihon Meisho Zue).

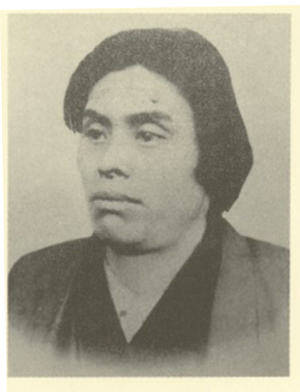

Hard Times

In 1899, after the death of one of his daughters, Kiyochika began a series of travels in the provinces which concluded in 1900 when he again turned to illustration work with the Niroku shinpo, a political newspaper. While working at the paper fraud charges were brought against him for accepting money to suppress a series of critical articles about a distant family relation of his wife. Kiyochika was forced to resign from the paper and three difficult years followed until the start of the Russo-Japanese War in 1904 when publisher's again asked for designs of battle prints. However, by 1904 woodblock prints were already in decline as the new western technologies of lithography and photography fed the public's desire for realistic depictions of battle scenes, and times remained difficult for Kiyochika and his family. In 1906 he and his family moved to Fujimi-cho, a former district for retainers of the shogun. In 1913, after the death of his wife Yoshiko, Kiyochika traveled again, making sketches for his final landscape series commissioned by Matsuki Heikichi and published after his death. He returned to his home in October of 1915 where he died on November 28th.  Kiyochika at Age 60 |  The Grave of Kobayashi Kiyochika The Grave of Kobayashi KiyochikaRyufuku-ji Temple, 3 chome 17-2, Moto-asakusa Source: A Guide to the Taito City’s Historic Sites and Noted Places |

Fame After Death

While alive, Kiyochika's greatest fame was as a cartoonist, illustrator and designer of war prints, but shortly before his death an interest in his early woodblock prints was kindled by the poet and dramatist Kinoshita Mokutaro (1885-1945). Mokutaro, along with the writers Nagai Kufu (1879-1959) and Yone Noguchi (1875-1947) wrote about Kiyochika's art and sparked a rediscovery of the artist that continues until this day. Noguchi's article Kiyochika Kobayashi: A Modern Master of the Japanese Color Print written shortly after Kiyochika's death is reproduced in the Article section of this site.Kiyochika's Students

Despite Kiyochika's independence from any art lineage and disinterest in creating his own lineage, he did open his own art school in 1894 and take on several students. Two of his students, Inoue Yasuji (1864 - 1889) and Taguchi Beisaku (1864-1903), became well known designers of woodblock prints. Of the two, Yasuji was the most influenced by his master, copying his style to the extent that much of his work is almost identical to Kiyochika's. Beisaku, who was a later student of Kiyochika's, is primarily known for designing artistic war triptychs that showed an innovative use of color and tone. The shin hanga artist Tsuchiya Kōitsu (1870-1949) was part of Kiyochika’s household from about 1886 to 1900 and one can see Kiyochika's influence on his student's landscape prints.Signatures and Seals

Source: Kiyochika: Artist of Meiji Japan, Henry D. Smith II, Santa Barbara Museum of Art, 1998, p. 13-14.Kiyochika's earliest prints used the gō (art name) Hōensha 方円舎 and his given name Kiyochika 清親. "The use of one's given name in a signature was virtually unprecedented in the history of Japanese art, and at the time could have only have been used by those working in a purely Western style of painting..." On the Tokyo landscapes, he usually signed horizontally, often from left to right in the Western manner. He often appended hitsu (from the brush of) [or ga (drawn by)] to his name, as did many Japanese artists. In 1894 he took a new art name Shinsei 真生, written with the kanji for 'truth' and 'birth'. Kiyochika used Shinsei or simply Shin 真 for the rest of his life, although after the 1880s it appears on seals and not as part of his signature. In the late 1880s, Kiyochika began to drop the family name, Kobayashi, in his signatures and signed works simply Kiyochika. "In effect, his given name had in time become his art name, and on both paintings and prints from the 1890s until the end of his life, Kiyochika always signed simply 'Kiyochika,' reserving the family name Kobayashi for seals."

from an 1880 Tokyo landscape print |  |   |   |

|  |  |  |  |

|  |  |  from March 1898 scroll |  |

Literature

Kiyochika: Artist of Meiji Japan, Henry D. Smith II, Santa Barbara Museum of Art, 1998.1 Smith does note that Kyosai was an "old friend" of Kiyochika's and that Kiyochika drew on Kyosai's spirit for much of his comic work.

2 Kiyochika: Artist of Meiji Japan, Henry D. Smith II, Santa Barbara Museum of Art, 1998, p. 8.

3 Beyond the Great Wave, James King, Peter Lang, 2010, p. 125.

last revision:

7/28/2021